The Baseball Writers Association of America Needs To Go Part II

Still more strange decisions from the "esteemed" body of baseball minds

The last time I was found in your inboxes I was delivering a post about the ridiculousness that is the Baseball Writers of America Association. Click the link if you missed it or just want to relive the stupidity contained therein.

Today, I’m going to finish up my look at the BBWAA and their stranglehold on Major League Baseball post-season awards, and Hall of Fame voting. Let’s jump right in.

Ridiculous Rookie of the Year picks

In 1979, the American League Rookie of the Year was given to both Minnesota Twins infielder John Castino and Toronto Blue Jays shortstop Alfredo Griffin in a tie vote. Castino finished the season hitting .285, with five homeruns, 52 RBIs, five stolen bases, with an OBP of .331, a SLG of .728 in 148 games. Griffin ended the season hitting .287, with two homeruns, 31 RBIs, 21 stolen bases, with an OBP of .333, a SLG of .364 in 153 games. Pretty underwhelming totals for Rookies of the Year.

The true Rookie of the year in 1979 should have been left-handed Chicago White Sox pitcher Ross Baumgarten. He finished the year with a 13-8 record, an ERA of 3.54, four complete games, three shutouts, while striking out 72 in 192-2/3 innings. I don’t know what made the voters pick Castino and Griffin but I think Baumgarten would have been a much better choice. Griffin had the longest career of the three, playing 1,962 games compared to Castino’s 666 games and Baumgarten’s 90 but that doesn’t factor in to the voting because no one knows how long a rookie’s career will be. I just think that for 1979, Baumgarten was a better choice.

The 1983 Rookie of the year was awarded to White Sox left fielder Ron Kittle. I think a much better choice would have been Baltimore Orioles right-handed pitcher Mike Boddicker. I know that there is an argument, especially back then, that pitchers shouldn't win the Cy Young award because they don’t play every day, but sometimes you find a pitcher with stats good enough to make that an irrelevant argument. I believe this is one of those years (I don’t buy the argument at all, but especially in this case).

Kittle finished the year hitting .254, with 35 homeruns, 100 RBIs, eight stolen bases, with an OPS of .314 and a SLG of .504 in 145 games. Quite a season for a rookie, but he also led the league in strikeouts, with 150, never a good way to start out your Major League career, especially then, when strikeouts were considered very bad (unlike now where no one seems to care). Just as an example the second place vote getter Julio Franco only struck out 50 times in 28 more at bats. Boddicker, on the other hand, was a mainstay in the rotation of the eventual World Series champion Orioles. He ended the season 16-8 with an 2.77 ERA, ten complete games, five shutouts, 120 strikeouts, and a WHIP of 1.078 in 179 innings. Kittle’s numbers, especially his homeruns and RBIs are impressive, but Boddicker really made an impact for a good team and that should have given him enough to win the award.

The 1992 Rookie of the Year vote should have been one of the closest of all time, but for some reason the voters decided differently. They awarded it to Milwaukee Brewers shortstop Pat Listach over Cleveland Indians center fielder Kenny Lofton. I think it should have gone to Lofton, or at least been a tie. As it was, it was not a close race, Listach won with 122 points while Lofton was second with 85. If you look at their numbers you will see that it wasn’t the runaway it turned out to be and I think you will agree that Lofton should have won the award.

Listach hit .290, with one homerun, 47 RBIs, 54 stolen bases, 55 walks, 124 strikeouts, with an OBP of .352, and a SLG of .349 in 149 games. Lofton finished with a batting average of .285, five homeruns, 42 RBIs, a league-leading 66 stolen bases, 68 walks, 54 strikeouts, with an OBP of .362, and a SLG of .365 in 148 games. If we look at it another way, Lofton hit five points lower, had four more homeruns, twelve more stolen bases (he was also caught less times, 12 versus 18 times). Lofton had 13 more walks, 70 less strikeouts. His OBP was ten points higher and his SLG was 16 points higher. Maybe Listach was a better fielder? No, not really. Both short and center are considered premium positions where good fielding is a must, but here Lofton gets the edge as well. Listach made 24 errors for a Fielding% of .966 while Lofton only made eight errors for a Fielding% of .982. Lofton also had a league-leading 14 outfield assists, meaning he threw out baserunners tagging on fly balls or that had strayed too far away from their base on a fly ball to center. I believe that taken in total, I have made the case for Lofton to be the Rookie of the Year in 1992.

In 1995, the BBWAA in their infinite wisdom, decided to give the Rookie of the Year award to Hideo Nomo, a player that had five years of experience in the Japanese Professional Baseball League. The BBWAA had fallen into the same trap that the Professional Hockey Writers’ Association had found themselves mired in, back in 1989. They should have learned from the mistake the hockey writers had made, but they didn’t. Just as a little background, I’ll quickly look at the case of NHL player Sergei Makarov. He had played in the Soviet Union for ten years before coming to North America in 1989. He had played in both their professional league and on their Olympic teams. When he came to the NHL he was awarded the Calder Memorial Trophy, for outstanding rookie, at the age of 31. He had 86 points in 80 games which is outstanding but, again he was 31 with ten years of international experience. The pick caused massive pushback all over the NHL. In 1991 after the uproar surrounding Makarov’s win, the NHL changed the rules, stating that a player had to be 25 or younger to be eligible to win the award. The BBWAA would have known this, and should have never given a “rookie award” to a player who had been playing high level pro ball for five years. This isn’t the only time it happens either.

The award should have gone to 23-year-old Chipper Jones, he ended the season hitting .265 with 23 homeruns, 86 RBI, eight stolen bases, an OBP of .353, and a SLG of .450 in 140 games. He was the starting third baseman for the eventual World Champion Atlanta Braves, and also played right and left field. He was third on the team in homers and second in RBIs, quite a season for a rookie. Nomo, on the other hand, finished the season 13-6 with an ERA of 2.54, four complete games, three shutouts, a league-leading 236 strikeouts and a WHIP of 1.056 in 191-1/3 innings. He had a great season, I’m not taking anything away from him. I just think someone who played pro baseball, in a high quality league for five years, shouldn’t be eligible to be called Rookie of the Year.

In 2000 the BBWAA made the same mistake they had made in 1995 and gave the Rookie of the Year award to Kazuhiro Sasaki, another Japanese player. Sasaki pitched for the Seattle Mariners, but he had played professional baseball in Japan for ten years before coming to the United States. To make it even worse, Sasaki was a relief pitcher who only pitched 62-2/3 innings that year. The award should have been given to Terrence Long, Mark Quinn Mark Redman or Barry Zito. I’m not saying that Sasaki didn’t have a good year, he did. He was 2-5 with an ERA of 3.16, 37 saves, 78 strikeouts, and a WHIP of 1.165 in those 62-2/3 innings.

Oakland A’s center fielder Terrence Long finished the season hitting .288 with 18 homeruns, 80 RBIs, five stolen bases, an OBP of .336, and a SLG of .452 in 138 games. Kansas City Royals left fielder Mark Quinn finished the season hitting .294 with 20 homeruns, 78 RBIs, five stolen bases, an OPS of .342, and a SLG of .488 in 135 games. A’s left handed pitcher Barry Zito was 7-4 with a 2.72 ERA, one complete game, one shutout, 78 strikeouts and a WHIP of 1.176 in 92-2/3 innings. Minnesota left hander Mike Redman finished the season 12-9 with an ERA of 4.76, 117 strikeouts and a WHIP of 1.407 in 151-1/3 innings. If I had a vote, I would have picked Long, I know that Quinn had more homers and a better batting average but he only had two homers more and played in less games. You could make an argument for any of those players winning, but I think it is a travesty that a 31-year-old guy that had been playing pro ball for ten years, won the award. It happens again in 2001 but the case against Ichiro isn’t nearly as strong. He was 26, only had six years of pro ball in Japan, and had one of the greatest seasons in recent memory.1

Players Elected Too Late

The BBWAA have chosen to wait to induct some players until after they died and I think that might be the most horrible thing in this whole mess. I’m not talking about players that died before the Hall of Fame was opened, or players like Lou Gehrig or Roberto Clemente that died of an illness or accident. I’m talking about players that retired and waited for years to get the call, died and then were elected. In my opinion there is nothing more disgusting then robbing a player of their ability to enjoy their enshrinement in Cooperstown. I think this goes right to the heart of the issues with the BBWAA. I’m going to look at some of those unfortunate players.

Ron Santo

He played from 1960 to 1974 for the Chicago Cubs and Chicago White Sox. He was a nine-time All-Star, five-time Gold Glove winner. He was fourth in Rookie of the Year voting in 1960 and was in the top ten in voting for National League Most Valuable Player four times, and the top five twice (‘67 and ‘69). He led the National League in triples in 1964 and walks four times. He had a career batting average of .277 with 342 homeruns, 1,331 RBIs, an OBP of .362 and a SLG of .464 in 2,243 games. When Santo first became eligible for election to the Hall of Fame in 1980, he was named on less than four percent of all ballots cast by the BBWAA, resulting in his removal from the ballot shortly thereafter. He was one of several players re-added to the ballot in 1985 following widespread complaints about overlooked candidates, with the remainder of their 15 years of eligibility restored even if this extended beyond the usual limit of 20 years after their last season.

After receiving 13% of the vote in the 1985 election, his vote totals increased in ten of the next thirteen years until he received 43% of the vote in 1998, his final year on the ballot. He finishing third in the voting behind Don Sutton and Tony Perez. Following revamped voting procedures for the Veterans Committee, Santo finished third in 2003, tied for first in 2005 and alone in first in the 2007 and 2009 elections, but fell short of the required number of votes each year.2 Santo had been sick for a long time, everyone in baseball knew he didn’t have long, and he died in 2010. In December of 2011, the 16-member Golden Era Committee composed of players Hank Aaron, Pat Gillick, Al Kaline, Ralph Kiner, Juan Marichal, Brooks Robinson, Billy Williams, Al Rosen, manager Tommy Lasorda, executives Paul Beeston Bill DeWitt II, Roland Hemond, Gene Michael, as well as writers Jack O’Connell and Dave Van Dyck, began voting on ten candidates selected by the BBWAA screening committee (another problem, they should let the committee consider every player that had received at least 5% of votes in their regular time on the ballot). While Santo received enough votes to gain entry into the Hall of Fame, what were the difference between his stats in 2009 and 2011? Absolutely nothing, so the BBWAA chose to keep him out until after he was dead, robbing him of the chance to see his plaque in Cooperstown.

Dick Allen

He played from 1964 to 1977 for the Philadelphia Phillies, St. Louis Cardinals, LA Dodgers, White Sox and A’s. He was Rookie of the Year in 1964, AL MVP in 1972, he was also in the top ten in MVP voting in 1964 and 1966 and the top five in 1966. He led the AL in homeruns twice (‘72 & ‘74). In 1972 he also led the AL in RBIs and walks, and in 1964 he led all of baseball with 13 triples. He had career batting average of .292 with 351 homeruns, 1,119 RBIs, an OBP of .378, and a SLG of .534 in 1,749 games. He was finally elected to the Hall of Fame in 2025 by the Classic Baseball Era Committee, five years after he died. Detractors of Allen's Hall of Fame credentials argue that his career was not as long as most Hall of Famers, and therefore lacked the career cumulative numbers that others do. They also argue that the controversies surrounding him negatively impacted his teams.

Hall of Fame player Willie Stargell countered with a historical perspective of Dick Allen's time:

"Dick Allen played the game in the most conservative era in baseball history. It was a time of change and protest in the country, and baseball reacted against all that. They saw it as a threat to the game. The sportswriters were reactionary too. They didn't like seeing a man of such extraordinary skills doing it his way. It made them nervous. Dick Allen was ahead of his time. His views and way of doing things would go unnoticed today. If I had been manager of the Phillies back when he was playing, I would have found a way to make Dick Allen comfortable. I would have told him to blow off the writers. It was my observation that when Dick Allen was comfortable, balls left the park."

To put it another way, the mostly white sports writers kept Allen out of the Hall of Fame because he didn’t act the way they thought he should. The two managers for whom Allen played the longest, Gene Mauch of the Phillies, and Chuck Tanner of the White Sox, agreed with Willie Stargell, saying that Allen was not a "clubhouse lawyer" who harmed team chemistry.3 Asked if Allen's behavior ever had a negative influence on the team, Mauch said, "Never. Dick's teammates always liked him. I'd take him in a minute.” According to Tanner, "Dick was the leader of our team, the captain, the manager on the field. He took care of the young kids, took them under his wing. And he played every game as if it was his last day on earth."

Listed below are five other players that I think should have been enshrined long before their deaths. The Hall of Fame and the BBWAA should be ashamed of themselves for denying them the ability to celebrate their election to the Hall while they lived. I’m not going to profile all of them or this post will either be an hour long read or have to go to a Part III. Please look them up and decide for yourselves if they were robbed. The players are: Minnie Miñoso, Chuck Klein, Harry Heilmann, Nellie Fox and Mordecai “Three Fingers” Brown.

Hall of Fame Snubs

There are thousands of MLB player that are not in the Hall of Fame and the vast majority of them don’t belong there, they just weren’t good enough or only had a very small window of success (i.e. Roger Maris or Denny McLain). There are a handful of players that have the numbers and success to be enshrined, but for various reasons have not yet been bestowed with the honor. It seems like it is just another example of the BBWAA not doing their job correctly.

Bill Freehan

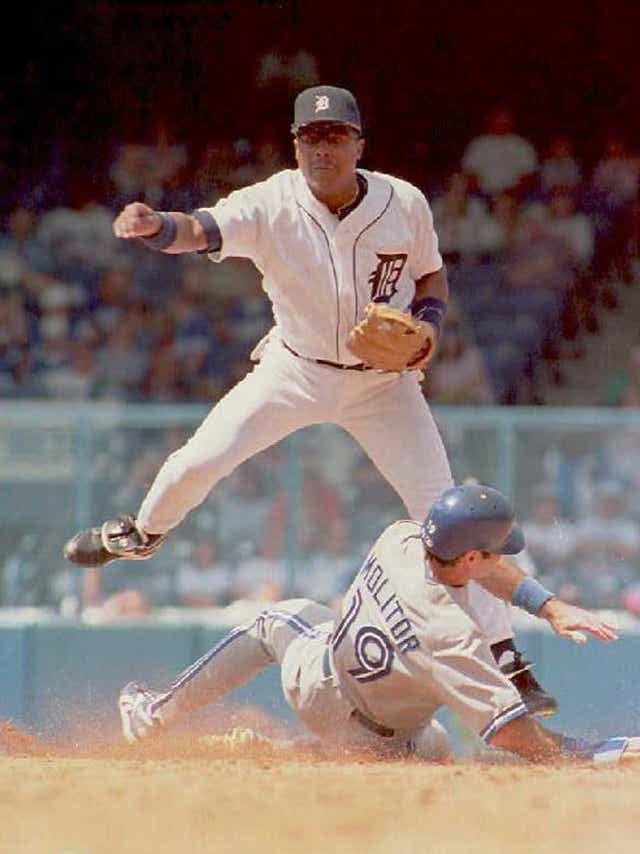

He played from 1964 to 1976 for the Detroit Tigers and was the starting catcher on their World Series Championship team of 1968. He was an eleven-time All-Star, a five-time Gold Glove winner and was in the top ten in MVP voting three times. He led the league in intentional walks once and hit by pitch three times. He finished his career with a batting average of .262, 200 homeruns, 758 RBIs, an OBP of .340, and a SLG of .412 in 1,774 games. He had a career Fielding % of .993, a Major League record until 2002, in fact he never made more than eight errors in a season, all at the hardest position in baseball. He was considered the quiet leader of that 1968 team.

In a year marked by dominant pitching, he posted career highs with 25 home runs and 84 RBI, fifth and sixth in the AL respectively. Freehan broke his own records with 971 putouts and 1,050 total chances, marks which remained league records until Dan Wilson topped them in 1997 with Seattle. He was also hit by 24 pitches, the most in the AL since Kid Elberfeld in 1911. Despite playing in hitter-friendly Tiger Stadium, Freehan guided the Tigers' pitching staff to an ERA of 2.71, third best in the league. Denny McLain won 31 games and Mickey Lolich won 17 as the Tigers ran away with the pennant. Because of his offensive and defensive contributions, he finished second to McLain in the 1968 MVP voting. In his book, The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, baseball historian Bill James ranked Freehan 12th all-time among major league catchers, and all of the eleven catcher ranked higher, and the thirteenth ranked catcher (Ivan Rodriguez), are already in the Hall of Fame.4

Lou Whitaker

Another Tiger, this one a second baseman, who played from 1977 to 1995. He was the starting second baseman on the 1984 World Series Championship team and the 1,100 double plays he turned in 19 years with Alan Trammell are a Major League record. He was Rookie of the Year in 1977, five-time All-Star, three time Gold Glove winner, and four time Silver Slugger winner.5 “Sweet” Lou finished his career hitting .276 with 244 homeruns, 1084 RBIs, an OPS of .363, and a SLG of .426. Whitaker appeared in 2,390 games for the Detroit Tigers, third most in franchise history behind Ty Cobb and Al Kaline. He also ranks fourth in major-league history with 2,308 games played at second base.

He remains among the Tigers' all-time leaders in double plays (first, 1,527), assists (second, 6,653), bases on balls (second, 1,197), and runs scored (third, 1,386). Bill James ranked him the thirteenth best second baseman in MLB history. Eleven of the twelve players listed before Whitaker are already in the Hall of Fame (Bobby Grich is #12 and isn’t in the Hall, but should be). Whitaker was first considered for election to the Hall of Fame in 2001 but only received 2.9% of the vote. In 2020, he was considered by the Modern Baseball Era Committee, but fell short of the required 75% threshold for induction, receiving six votes, 37.5%, from the 16-member committee. Whitaker's exclusion from the Hall (particularly him falling off the BBWAA ballot after a single year) has been widely criticized by baseball fans. He meets multiple Hall of Fame standards such as him reaching 2,000 hits and playing with one team his entire career, plus, it just doesn’t feel right that Alan Trammell is in the Hall without his double-play partner.

Curt Schilling

He pitched for five teams (Baltimore, Houston, Philadelphia, Arizona and Boston), from 1988 to 2007. He was a World Series Champion in 2001, 2004 and 2007, and the World Series MVP in 2001. He was a six-time All-Star, and in the top ten in MVP voting twice. He led the National League in wins, complete games, innings pitched WHIP and strikeouts twice. He finished his career with a 216-146 record, 83 complete games, 20 shutouts, 22 saves, 3,116 strikeouts, an ERA of 3.46 and a WHIP of 1.137 in 3,261 innings pitched over 569 games. In the playoffs, where he seemed to be his most dominant, he was 11-2, with four complete games, two shutouts, an ERA of 2.23 and a WHIP of .9680 in 133-1/3 innings over 19 games.

Schilling has had many brushes with the press over his career as well as after his playing days were over. As a member of the 3,000 Strikeout Club, induction in the Hall of Fame is all but assured. In fact, of the nineteen players in that club, fifteen are already in the Hall. Only Justin Verlander and Max Scherzer, who are still active players, Roger Clemens (who we will talk about in a bit), and Schilling are not yet enshrined. Schilling himself, blames the BBWAA and a left-wing bias for his lack of BBWAA support. In 2021 Schilling wrote on social media:

“I will not participate in the final year of voting (for the Class of 2022). I am requesting to be removed from the ballot. I’ll defer to the veterans committee and men whose opinions actually matter and who are in a position to actually judge a player.”

Washington Post sports columnist Barry Svrluga suggests that Schilling is simply the guinea pig of a problem long percolating in the process. He writes:

“Curt Schilling sure doesn’t seem like a Hall of Fame person. But that doesn’t mean he wasn’t a Hall of Fame player. He wants to extract himself from the process because he’s ‘mentally done’? Fine, whatever. What’s more important is that the process be overhauled and the Hall return to being a celebration of the best to play the game rather than an annual exercise in ethics and morality in which the people tasked with documenting the honorees also determine them.”

As I said in Part I, the Hall of Fame is filled with horrible people that did horrible things, but were amazing baseball players. I think it is long past time for the BBWAA and the Hall of Fame to get down from their high horses and just elect the best baseball players. Bill Freehan, Lou Whitaker and Curt Schilling are among the best and deserve to be in the Hall of Fame.

Steroids

There are three players that definitely have the numbers to get them elected to the Hall of Fame, but one thing is holding them back; Performance Enhancing Drugs (PEDs).

Barry Bonds

Seven NL MVP titles, most homeruns in MLB history, most walks in MLB history, most intentional walks in history, fourteen-time All-Star, eight Gold Gloves, and twelve Silver Sluggers, among other records. His Hall of Fame resume shouldn’t require much explanation.

Bonds might be the greatest player many of us have seen in our lifetimes. He had accrued surefire Hall of Fame credentials before his alleged PED use, clouded the picture. The BBWAA refused to vote him in, and he didn't fare any better with the Today's Game Era Committee, meaning that it's hard to see Bonds reaching Cooperstown anytime soon.

Roger Clemens

Seven Cy Young Awards, two pitching Triple Crowns, AL MVP award, third-most strikeouts in history and eleven-time All-Star, along with many other insane stats, give “The Rocket” an argument to claim the title of Best Pitcher of All-Time.

Just like Bonds, he had a Hall of Fame resume before he began his alleged use of PEDs. But like Bonds, Clemens did not have an easier time with the Today’s Game Era Committee than he did with the BBWAA.

Alex Rodriguez

Three-time AL MVP, fourteen-time All-Star, two-time Gold Glove winner, ten-time Silver Slugger, fifth all-time in homeruns, along with many other eye-watering numbers make A-Rod one of the greatest shortstops/third basemen to play the game.

But, thanks to multiple transgressions with performance-enhancing drugs, including a year-long suspension from baseball in 2013-14, Rodriguez received only 34.8% of the vote in 2024. He will now have to endure the waiting game while BBWAA voters decide what to do about him. Just like Bonds and Clemens.

The baseball world in general, and the BBWAA and Baseball Hall of Fame specifically, need to decide what to do with the “Steroid Era” ball players. As I have quickly shown there are players that have the numbers to get in, but are being kept out because of the, for lack of a better term, “morality clause”. The “enlightened” modern voter seems to have taken up the cause of “saving baseball” from the “cheaters” in today’s game. Never realizing that the history of PEDs in baseball goes back long before now. As I said in Part I, a player named Pud Galvin took injections of monkey testosterone as early as 1889. The Great Bambino himself once tried an injection of an extract derived from ram testicles. In World War II, both the Allied and Axis powers provided amphetamines, on a large scale, to their troops, in order to improve soldiers' endurance and mental focus. After the end of the war, many of those returning troops applied their knowledge of the benefits of amphetamine to sports, including professional baseball. Mickey Mantle tried to get an advantage in his 1961 homerun race with teammate Roger Maris by getting an injection of a cocktail including both steroids and amphetamines. Hank Aaron admitted to taking an amphetamine tablet once. Tom House, a pitcher who played from 1971 to 1978, acknowledged taking steroids his whole career.

Obviously, drug use has a long and storied history and isn't the new and immediate problem the writers and uninitiated public seem to think. The public also seem to think that taking PEDs is like a highway to 70+ homeruns, again, not true. Most baseball players take PEDs to recover quicker from the nagging aches and pains that come from playing 162 games (or up to 217 including Spring Training and the postseason), from February to November. Taking Human Growth Hormones (HGH) does help build bigger muscles but you still have to be able to hit the ball.

Hitting a baseball is the hardest thing to do in sports, and taking PEDs isn’t going to help you much, unless you are already very good at it. As a lifelong baseball guy, who wasn’t even good enough to play in high school, you could give me all the PEDs ever made. And, while I might look like the Hulk, I wouldn’t hit very many homeruns, I just don’t have the vision, hand-eye coordination, or the quick-twitch muscles required to hit a baseball travelling between 85-105 miles per hour.

So, should the BBWAA and the HOF just ignore the PED use, and elect Clemens, Bonds and A-Rod? I think that is exactly what they should do. There is plenty of evidence that PED use was widespread enough to make it an even playing field, and they should just go with the numbers as they are. You may call them cheaters, and you would be right, but if enough players were cheating, it’s as equal as it ever could be. Some people draw a moral equivalency between PED use and betting on baseball and say that if the juicers get in Pete Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson should as well. You can’t draw an equivalency between the two because, while using PEDs might help you win, betting on baseball casts a pall over the integrity of the game. Did Chris just drop that easy ground ball, because he bet on the Tigers to lose? Did he just take a changeup down the middle, with the bases loaded, because he bet the under? Those are much more sinister questions that call the fabric of the game into question, certainly much worse then players trying to pump up their numbers.

The BBWAA and the Hall of Fame need to take themselves down a peg and vote for the best players regardless of what foibles they may have. Baseball writers have made moral compromises with votes in the past. If you look at the history of the Hall of Fame, as we have seen, we have all sorts of rogues, reprobates and wife beaters already enshrined. I don’t think PED use is anywhere near the worst offense committed by players already in the Hall. But the poor showing by Bonds and company, suggest baseball writers still see steroids as something more ominous. We love sports, because it showcases human athletes performing superhuman feats. We want to believe these men can perform the unthinkable, yet we are quick to dish out punishment when athletes veer into the shadows to quench the desire of the public to see those prodigious feats.

Journalists’ pride themselves in their ability to find nuance in their stories. But to be fair to baseball writers, the Hall of Fame presents an inherently black-white dichotomy: A player is in, or he’s out. It’s a choice inherently at odds with the infinite shades of gray, in real life. It creates a wilderness for voters to navigate, such is the burden of those with the power to bestow immortality. They should leave the integrity and character completely out of voting and go by the numbers to paraphrase Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart “I’ll know a Hall of Famer when I see one”.

While you can argue that some players may not deserve it, other sports simply don’t have these kinds of processes. The Pro Football Hall of Fame certainly has its issues and logjams annually. But the voting process differs greatly, and there’s an actual conversation had amongst the voters, rather than just sending ballot out to all eligible voters. Where there is never a guarantee that the ballots would be completely filled out, or filled out in a way that represents the actual talent of the players on it. If reforms are not undertaken, players like Schilling, Freehan, Whitaker and others will continue to suffer at the hands of voters who either don’t take their voting privileges seriously or have axes to grind and who are doing the game a bigger disservice than it would be to allow these players entry into Cooperstown.

I could go on and on on this topic, I didn’t even address the controversy surrounding the BBWAA and their unwillingness to vote a player in unanimously.6 There are so many other issues I could look at, that this could turn into a Disney Ruined Star Wars nine part rant, but I think I’ve made my point. The BBWAA and the National Baseball Hall of Fame need to seriously reform the voting process, and this will be a yearly issue until they choose to fix it. I hope everyone has enjoyed this two part series. Please feel free to share it with anyone who might be interested.

Chris

Ichiro finished the season with a League-leading .340 batting average, MLB-leading 242 hits, eight homeruns, 68 RBIs, a MLB-leading 58 stolen bases, an OBP of .381, and a SLG of .457 in 157 games. He also won the American League MVP, was an All-Star, won a Gold Glove, and a Silver Slugger award. A memorable season for anyone.

The Veterans Committee was made up all living members of the Hall, plus recipients of the Ford C. Frick award given to broadcasters, and the J.G. Taylor Spink Award given to baseball writers. Elections for players retired more than 20 years were held every other year and elections for managers, umpires and executives, every fourth year.

An outspoken player given to complaining and talking of reform and "rights". Joe Garagiola commented: "A clubhouse lawyer is a .210 hitter who isn't playing. He gripes about everything. His locker is too near the dryer. His shoes aren't ever shined right. His undershirt isn't dry. His bats don't have the good knots in them that the stars' bats have. He's not playing because the manager is dumb. When he does play he says, 'Well, what do you expect? I ain't played in two weeks.' And he's a perpetual second guesser."

Just in case you were wondering the other eleven catchers are in order: Yogi Berra, Johnny Bench, Roy Campanella, Mike Piazza, Mickey Cochrane, Carlton Fisk, Bill Dickey, Gary Carter, Gabby Hartnett, Ted Simmons and Joe Torre.

The Silver Slugger Award has been awarded annually since 1980 to the best offensive player at each position in both leagues. It is voted on by coaches and managers of the MLB teams but they are not allowed to vote for players on their own team. It was meant to clarify the difference between offensive and defensive talent regrading the Gold Glove Award, since those votes seemed to be about offensive success per 1980.

Mariano Rivera is the only player to be voted in unanimously. He received all 425 votes cast in 2019. Ichiro Suzuki is the next highest with 99.7% of the vote or 393 out of 394 votes cast. Derek Jeter also received 99.7% but it was 396 out of 397 votes. Babe Ruth received 95.1% of the vote in 1936, or 215 of 226 votes.

Yes--I am biased--Whitaker should be in. Nice breakdown of everyone. Funny when you look at the stats the rookies of the year put up in the late 70s/80s compared to later years--kind of pedestrian.