The Baseball Writers Association of America Needs To Go Part I

Their flawed and suspect voting for the Baseball Hall of Fame is only one issue

Last time I visited your inbox it was to deliver a post about Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his life before the assassination that made in famous. Click the link below if you missed it.

Today I want to talk about something that bugs me every January, and every time I think of it. How does the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA), work, how do they vote on who gets in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and wins the MLB awards and what kind of back room shenanigans go on there? There have been way too many snubs, controversies and omissions to believe that everything that goes no inside that organization is totally above board.

There are going to be a few baseball stats in this post and you can read a little bit about them in the footnotes. Also this post, like most of my, has a lot of pictures and you probably won’t be able to read the whole thing in the email. Just click on the title and read it in its entirety in the app or on the website.

People have long criticized and even openly questioned why the BBWAA is involved in the award and Hall of Fame voting process. There have been instances of “voting members” who once covered baseball but now cover one of the other major sports, but who still vote on who should be in the Hall of Fame or National League MVP. There are other reporters who believe that no one should ever be an unanimous selection and will not vote for a player that is a shoe-in. There are still others who let their personal feelings for certain players or teams affect their vote. The entire process is hidden behind a vail of corrupt secrecy and doesn't properly serve the baseball world or even the places these “experts” write for.

The History of the BBWAA

The BBWAA was founded on October 14, 1908, in order to improve working conditions for sportswriters, promote uniformity of scoring methods, and to professionalize the press box, limiting access to appropriate parties.

The organization began with 43 founding members. They included Joseph Jackson, who became the association's first president. At the time, Jackson was the sports editor of the Detroit Free Press. Also selected as officers were Irving Sanborn of the Chicago Tribune, Tim Murnane of the Boston Globe and syndicated columnist Hugh Fullerton. A second meeting was held in New York City in December where Sanborn decided he could not serve as an officer at that time, and he was replaced by William Weart of the Philadelphia Times. The slate of officers was ratified, and anyone who wrote about baseball in major league cities was eligible for membership. In December of 1913, membership was opened up to minor-league baseball. Jackson became the dominant force in the early years of the BBWAA, serving as president of the association for nine consecutive terms. In 1918 when Jackson finally retired, Sanborn returned to assume the position of president and Jackson became a member of the BBWAA Board of Directors.

Currently there are at least 700 members of the BBWAA, but there could be more as a writer does not have to disclose their membership in the organization. The organization's primary function is to work with Major League Baseball and individual teams to assure clubhouse and press-box access for BBWAA members. In addition, BBWAA members also elect players to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the organization's most public function. All writers with 10 continuous years of membership in the BBWAA, plus active BBWAA membership at any time in the preceding 10 years, are eligible to vote for the Hall of Fame. The BBWAA also votes annually for one winner from each league (American and National) of the Kenesaw Mountain Landis Most Valuable Player Award, Cy Young Award, Jackie Robinson Rookie of the Year Award and Manager of the Year Award. The Hall of Fame also charged the BBWAA's Historical Overview Committee, of 11 or 12 veteran BBWAA members, to formulate the annual ballot for the Veterans Committee. In 2007 the BBWAA opened its membership to web-based writers employed on a full-time basis by "websites that are credentialed by MLB for post-season coverage."

Now that I have outlined a short history of the BBWAA, I will begin to look at the history of questionable award voting they have made throughout their history. This is not a new problem, as it goes back to the very beginning of their voting for both the Hall of Fame and the post-season awards. As we start this process, let’s first look at what the BBWAA use to make their votes. According to their website:

Voting shall be based upon the player's record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.

Right there I have an issue. Some of the players who have been elected to the Hall of Fame were horrible people. Babe Ruth and Mickey Mantle are two examples that come to mind. Mantle's drinking became public knowledge during his lifetime, but the press kept quiet about his marital infidelity and philandering, even though he wasn’t even trying to hide it. At his retirement ceremony in 1969, he brought his mistress and his wife (that must have been really awkward)! In 1980, Mantle separated from his wife, and while the two lived apart for the rest of Mantle's life, they never filed for divorce and he drank himself to death. Babe Ruth was even worse. The Babe was married twice in his baseball career, his first marriage ended in 1925, because of his repeated infidelities and neglect. His second marriage to actress Claire Merritt lasted the rest of his career but didn’t stop his over the top behavior. Yankees owner, Cap Huston, asked Ruth to tone down his lifestyle, Ruth replied, "I'll promise to go easier on drinking and to get to bed earlier, but not for you, for the money, but I won’t give up women, they're too much fun.” His roommate on Yankee road trips, Ping Bodie (they just name people like this anymore), said that he was not Ruth's roommate while traveling "I room with his suitcase". Where is the integrity and character of either of these players? A detective hired by the Yankees to follow him one night in Chicago reported that Ruth had been with six women. Of course, both of those players were elected long ago. Ruth was in the inaugural class in 1936 and Mantle was elected in 1974, back when the press thought that an athlete’s personal life was personal and only reported on the on-field exploits of these flawed men. The hall is full of figures who fall short of those lofty and vague ideals. Rogers Hornsby was hated by teammates and constantly bet on the ponies. Cap Anson was a virulent racist who helped to deepen segregation in the game. Pud Galvin received injections containing monkey testosterone (sound sketchy even by today’s standards). Gaylord Perry illegally doctored his pitches (I don’t have a problem with this but it is cheating). Nevertheless, the criteria still exist and modern writers are using it to keep players, they don’t like out of the Hall. If we look at some of the more egregious award voting the trend of the BBWAA writers not knowing what their doing, or having some kind of agenda continues.

Horrible MVP Votes

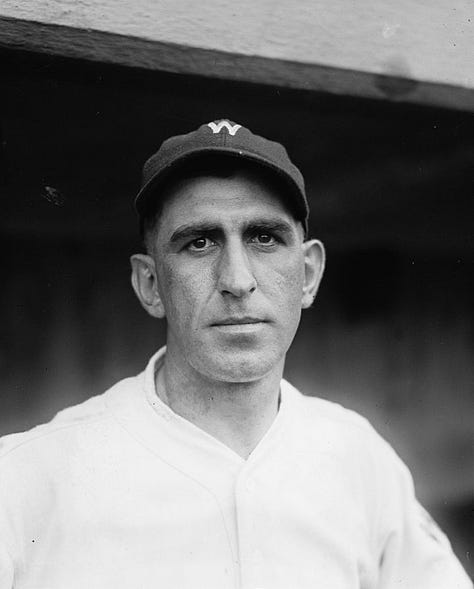

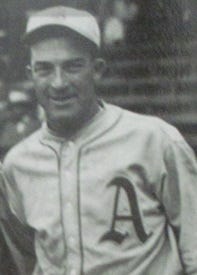

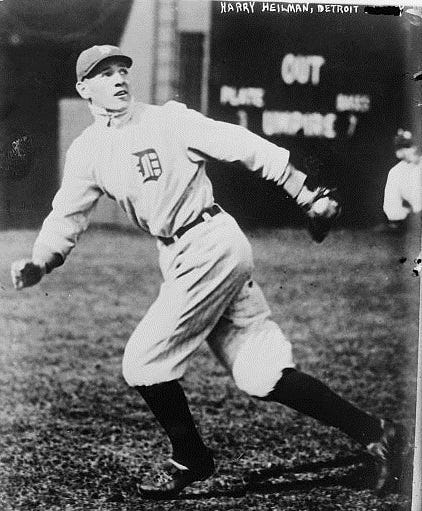

In 1925 the American League MVP went to Washington Senators shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh. He hit .294, four homeruns and 64 RBIs, with an OBP of .3671 and a SLG of .3792 in 127 games. Philadelphia Athletics' center fielder Al Simmons, hit .387, 24 homeruns and 124 RBIs, with an OBP of .419 and SLG of .599 in all 152 games that season. Detroit Tigers right fielder Harry Heilmann, hit .393, 13 homeruns and 134 RBIs, with an OBP of .457 and a SLG of .569 in 150 games. One BBWAA member from each of the eight American League cities3 were eligible to vote, a first place vote was worth 14 points, second place nine points, third place eight points down to one point for tenth place. When the voting was complete and the points tallied, Peckinpaugh won 45 points to 41, over Simmons, with Heilmann receiving 20 points. There was a belief in those days that a MVP winner should only come from a team that won the Pennant and the Senators won the AL Pennant, even though they would lose the World Series to the Pirates.

Either Simmons or Heilmann would have been a much better pick given their much higher offensive outputs. If you want to stick with the Pennant winner thing, then Senators pitcher Stan Coveleski would be a good pick. He was 20-5 with an 2.84 ERA, 15 complete games and three shutouts while striking out 58 (obviously a pitch to contact guy) in 241 innings. The Senators though so much of Peckinpaugh’s effort that he lost his starting shortstop job before the start of the 1926 season and would only play 125 games over the next two years.

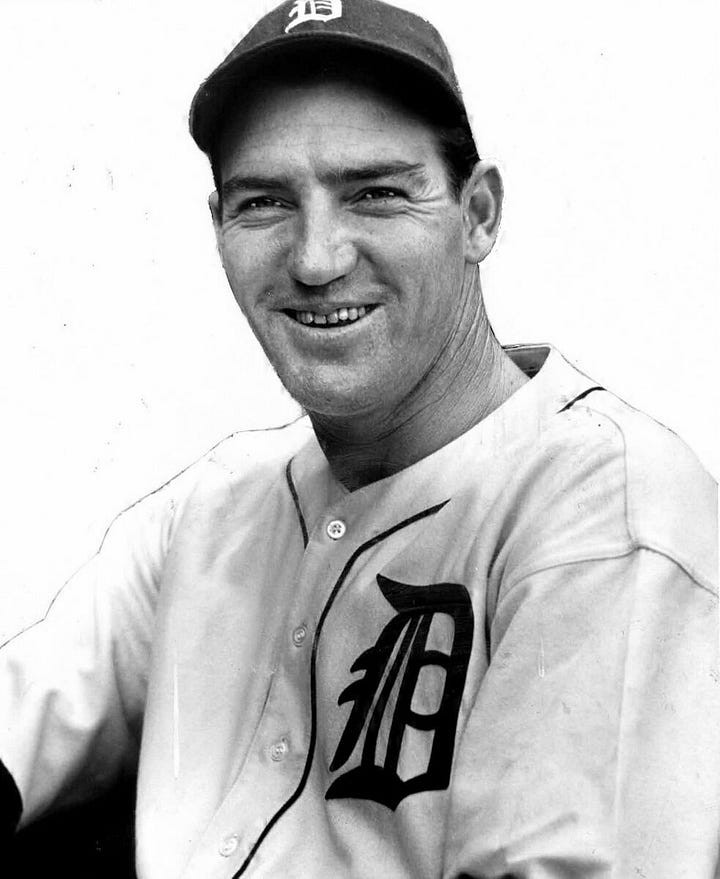

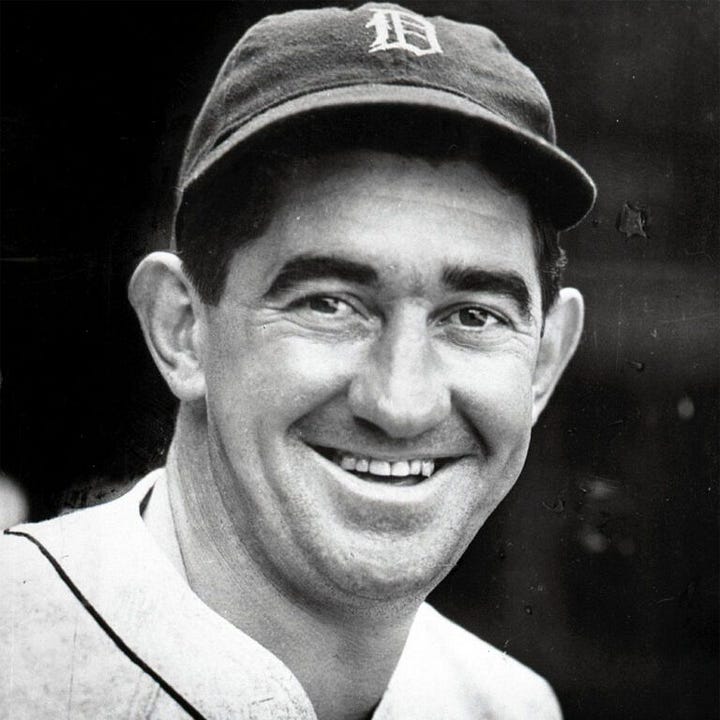

In 1934, New York Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig hit .363, 49 homeruns and 166 RBIs with an OBP of .465 and a SLG of .706 while playing in all 154 games. All of these totals led the MLB, and he won the Triple Crown.4 Tigers second baseman Charlie Gehringer hit .356, eleven homers and 127 RBIs with an OPS of .450 and SLG of .517 in 154 games. Yankees pitcher Lefty Gomez had a 26-5 record, a 2.53 ERA, with 26 complete games, six shutouts and two saves in 281-2/3 innings while striking out 158. Tigers pitcher Schoolboy Rowe was 24-8 with an ERA of 3.45, 20 complete games, three shutouts, and one save while striking out 149 in 266 innings. Mickey Cochrane, Detroit’s catcher/manager, hit .320, two homeruns and 75 RBIs, with an OBP of .428 and a SLG of .412 in 129 games. The voting was open to two sportswriters in each of the eight AL cities and when the points were counted, Mickey Cochrane was awarded the American League MVP with 67 points. Gehringer was second with 65, Gomez third with 60, Rowe fourth with 59 and Gehrig fifth with 54 points. How is this possible you might be thinking!

As I said, the Pennant winning team had the advantage in the voting in those days and the Tigers won the Pennant. Cochrane was a great defensive catcher, making only eight errors the entire season, and handling the Tigers' pitching staff with great skill. But why didn’t Gehringer win? He was a Tiger also, much better offensively and had the same fielding percentage as Cochrane. The writers at the time described Mickey Cochrane as one of the most inspiring, dynamic leaders in baseball history, and the bellwether of the Tigers pennant drive. So Cochrane was given the award for being a good leader and defensive catcher on the Pennant winning team. They disregarded what everyone else had done that season. If the vote had occurred anytime in the last 40 years Gehrig would win hands-down. The writers didn’t give Gehrig credit for winning the Triple Crown, because between 1901 and 1934 it had been won seven times and they didn’t realize how hard it really was.

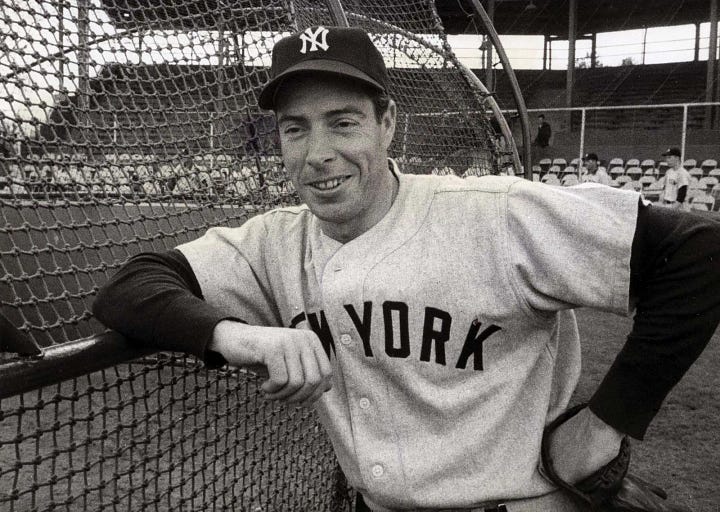

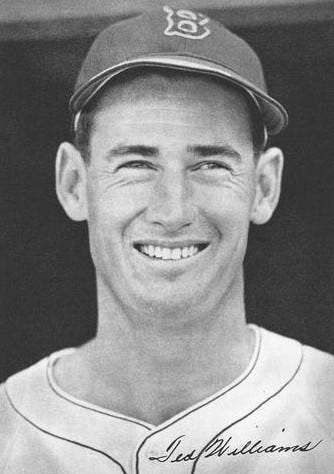

If voter spite is the measuring stick for BBWAA incompetence, the 1947 ballot worms its way to the top of the list. New York Yankees center fielder Joe DiMaggio hit .315, 20 homeruns and 97 RBIs, with an OBP of .391 and a SLG of .522 in 141 games. Boston Red Sox left fielder Ted Williams hit .343 with 32 homers and 114 RBIs, with an OBP of .499 and a SLG of .634 in 156 games. He also led the league in walks, runs scored and intentional walks and won the AL Triple Crown. In the closest vote in MVP history, Ted Williams lost the award to Joe DiMaggio by a single point (202–201). Williams was completely left off the ballot of one anonymous voter. Williams assumed for decades that it was one of the Boston writers with whom he had a less than congenial relationship. Eventually, it was discovered that it was Boston Globe sports writer Mel Webb that had left him off the ballot.

Even if it was a writer from a city other than Boston, there is no excuse to leave a player completely off the ballot. It shouldn’t matter what your relationship with the player is, it’s about how the player plays. The Yankees did win the Pennant that year, but supposedly the BBWAA had instructed the voters during World War II, not to take who won the Pennant into consideration. Williams was also snubbed in 1942 when he won the Triple Crown again and was better than MVP winner Joe Gordon (Yankees second baseman) in every offensive category except stolen bases. The writers really did not like the Splendid Splinter.

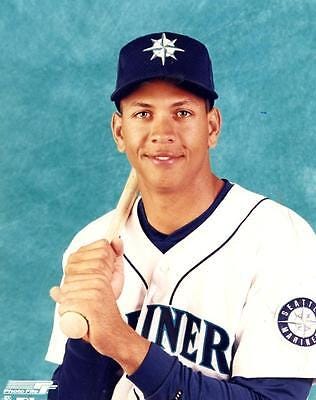

If your yardstick of incompetence, is the inexplicable selection of an unqualified player over a slew of seemingly superior candidates, then 1996 might be your cup of tea. Alex Rodriguez Seattle Mariners shortstop hit .358, 36 homers and 123 RBIs with an OBP of .414 and a SLG of .631 in 146 games. Mariners center fielder Ken Griffey Jr. hit .303, 49 homeruns and 140 RBIs with an OBP of .392 and a SLG of .628 in 140 games. Both of them while playing for a team that was ten games under .500 for the season. Cleveland left fielder Albert Belle hit .311, 48 homeruns and 148 RBIs with a OBP of .410 and a SLG of .623 in 158 games. Texas Ranger right fielder Juan Gonzalez hit .314, 47 homeruns and 144 RBIs with an OBP of .368 and a SLG of .643 in 134 games. When the votes were counted Gonzalez was the MVP. He garnered 290 points, while A-Rod received 287, Belle, 228 and Griffey Jr. 188 points.

Ranked by most offensive categories, Gonzalez wasn’t one of the top five players in the league (except in homeruns), while runner-up Alex Rodriguez was arguably the best player in the league. The Pennant “requirement” had long gone by the wayside by this point, so what could have been the reason Gonzalez won over much more qualified players? A writer from Oakland somehow placed Rodriguez seventh and both Seattle writers gave their first place votes to Ken Griffey Jr., which says something about the love A-Rod received in Seattle. But this vote probably came down to the Rangers making the playoffs and the Mariners falling short, which of course, shouldn’t have been a factor in the voting according to their own rules.

But if you rank your terrible MVP selections based on the level of dishonesty, hypocrisy, or bureaucratic incompetence surrounding a vote, there is only one choice for the worst MVP vote of all time, the 1999 MVP vote.

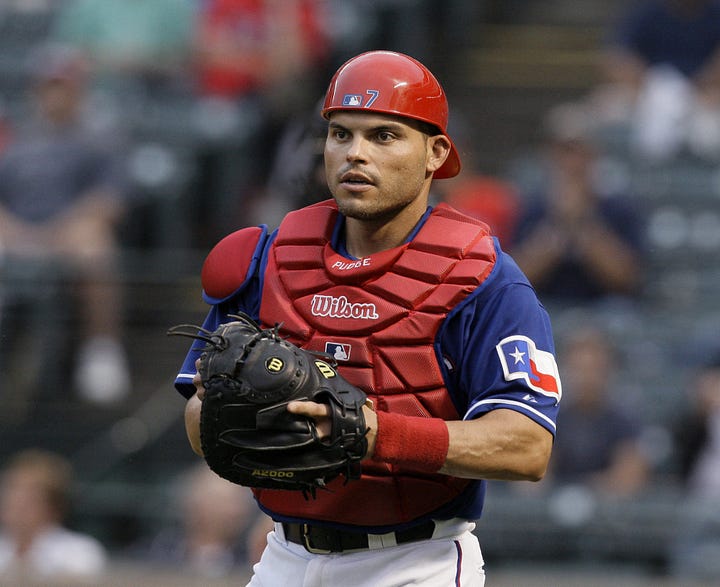

In 1999 Texas Rangers catcher Ivan Rodriguez was named 1999 AL MVP over Boston’s otherworldly right-handed pitcher Pedro Martinez. Martinez captured more first-place votes than Rodriguez, but was famously left off two ballots — omissions that cost him the award. Despite pitching in a hitter-friendly ballpark, Fenway Park, into an league-wide offensive onslaught what would average 5.18 runs per game, the twelfth highest runs per game in history, Martinez produced one of the great pitching lines of the last 100 years.

Martinez earned the pitching Triple Crown, leading the league in wins, ERA, and strikeouts, but that barely begins to capture his dominance. His ERA was more than a full run better than the next best in the league; and despite missing four starts to injury, he struck out 313 batters in season where only one other pitcher reached 200. Yet two writers; George King of the New York Post and La Velle E. Neal III of the Minneapolis Star Tribune, failed to even include the amazing Martinez on their ballot at all.

“What game were those guys watching?”

Ted Williams, regarding the 1999 MVP voting

Of the two snubs, Yankees beat writer George King’s “non-vote” was, at first blush, the more infuriating. Despite listing pitchers David Wells and Rick Helling on his ballot in 1998, King defended his treatment of Martinez by saying the “MVP is for everyday players. Pitchers have their own award.” The fact that King, would claim the “MVP is for everyday players”, a year after voting for two pitchers, was laughable. His snub of Martinez was so bad that his own newspaper called it “bunch of hogwash.” King’s hypocrisy was galling, but it’s Twins beat writer La Velle Neal’s snub of Martinez that differentiates this terrible MVP ballot from the dozens of questionable votes that have marked the award’s history.

Because La Velle Neal should not have been allowed to vote in 1999.

The controversy goes back to 1986. Yankees first baseman Don Mattingly was going to capture his second consecutive MVP award, it was a foregone conclusion, but the BBWAA voters had other ideas. Boston Red Sox ace Roger Clemens took the award with room to spare (19 first-place votes to five). The newS hit Yankee fans like a Clemens fastball to the head. New York newspapers decried the results in 40-point type splashed across the sport pages of every paper in the city. Adding fuel to the fire, Hank Aaron called the pick “a joke.” NL MVP Mike Schmidt was more diplomatic, but was also sympathetic to Mattingly: “Clemens may be an exception, he was so dominant. But I’m not in favor of a pitcher being considered for the MVP.” New York Mets ace and World Series champ Ron Darling was dumbfounded, he said:

“It’s hard for me to think how Mattingly could have lost the award. I’m one who believes everyday players should win.”

However, not everybody agreed that Mattingly was robbed. Hall of Fame right-hander (and 1968 NL MVP) Bob Gibson scoffed at the notion that a pitcher can’t be as valuable as an everyday player: “You can tell what I count for as a pitcher every time I go out there.” Ultimately, Jack Lang, secretary-treasurer of the Baseball Writers Association of America, quelled the debate by offering a warning to those writers who would suggest a pitcher should never win the award:

“The rules that are sent out to the voters on the [MVP] committee state: ‘Keep in mind that all players are eligible. That includes pitchers.’ Anybody that cannot vote for a pitcher, we replace them. In my 22 years running elections, only two writers have said that to me.”

This concretely established that BBWAA members are required to vote for pitchers if they think those players are deserving. Therefore, every writer eligible to vote was aware of the rules, then, why, did Neal have a vote in 1999?

In the aftermath of the 1999 vote, La Velle Neal was condemned in the media. Unlike George King, he met the harsh criticism with a “reasoned” defense of his ballot.

“I just feel that in order to be an MVP you have to be in the battle every day. If I believe a pitcher should not be in the running, why would I put him on the ballot at all?”

The logic is sound. If you’re being intellectually honest, you wouldn’t concede even a 10th-place vote to a pitcher if you believe pitchers aren’t eligible for the award. But striking pitchers from consideration violates not just the spirit of the rules, but the actual letter of those rules. It’s why, in the words of Jack Lang, the BBWAA disallows anybody who holds this position from voting. Did Neal neglect to inform the BBWAA of his stance on pitcher eligibility for the MVP? Did the BBWAA have knowledge of Neal’s anti-pitcher position, but choose to send him a ballot anyway, or have the rules regarding pitcher eligibility change since Roger Clemens took the award 39 seasons prior?

Only Lang (who passed away in 2007) and Neal know the answers to these questions. Except the last question, where the answer is “no”. Dennis Eckersley won the award in 1992 and Justin Verlander in 2011. Of course there have only been 22 times, in both leagues combined, where a pitcher has won, in the 93 years of the MVP award. What’s left is the fact that Pedro Martinez was cheated out of his rightful MVP by a procedural snafu, a miscommunication between the BBWAA and one of its members, or intentional deception on the part of a voter.

Head Scratching Cy Young Voting

The BBWAA also has a long history of messing up the Cy Young voting. Let’s look at some of the worse ones as well.

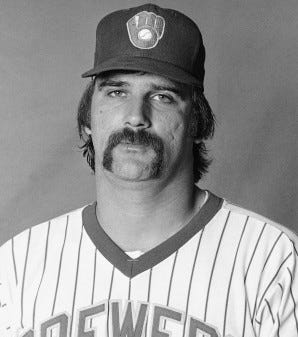

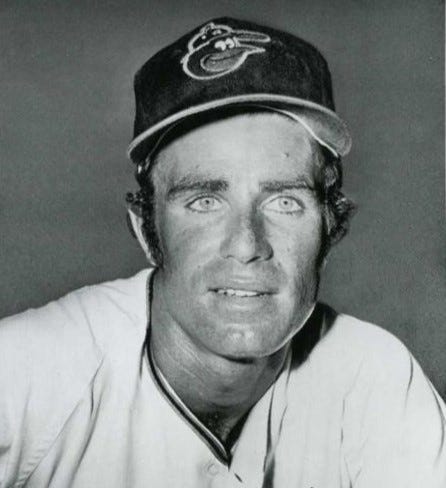

In 1982 the Cy Young Award went to Milwaukee Brewers right-hander Pete Vuckovich, who finished the season 18-6 with an ERA of 3.34, nine complete games, one shutout, 105 strikeouts, and a WHIP of 1.502 in 223-2/3 innings.5 Baltimore Orioles righty Jim Palmer was second in voting. He finished the season 15-5 with an ERA of 3.13, eight complete games, two shutouts, one save, 103 strikeouts and a WHIP of 1.137 in 227 innings at the age of 36.

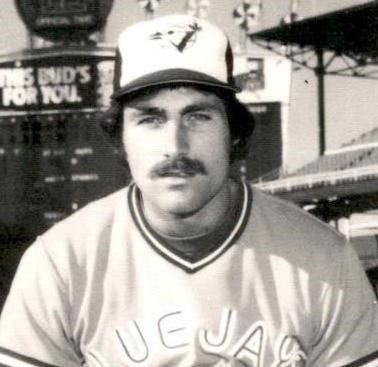

However, it was the fourth place pitcher that should have won the award. Toronto Blue Jays right-hander Dave Stieb finished the season at 17-14 for a Jays team that was ten games under .500. He had an ERA of 3.25, nineteen complete games, five shutouts, 141 strikeouts, a WHIP of 1.200 in 288-1/3 innings of work. I’m sure voters were put off by the record of the Blue Jays but Stieb was better than Vuckovich is every category beside strikeouts. All of that while playing for a team that could not support him. The Jays scored the 2nd least runs in the league yet Stieb had the third lowest ERA of any of the top twenty pitchers in Innings Pitched. Palmer also had a better season than Vuckovich, for an Orioles team that only finished one game behind the Brewers in the standings, and as the seventh oldest pitcher in the league. He already had three Cy Young Awards so the voters wanted someone else to win.

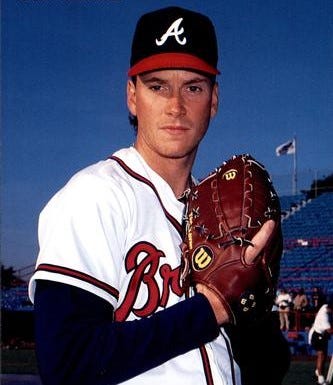

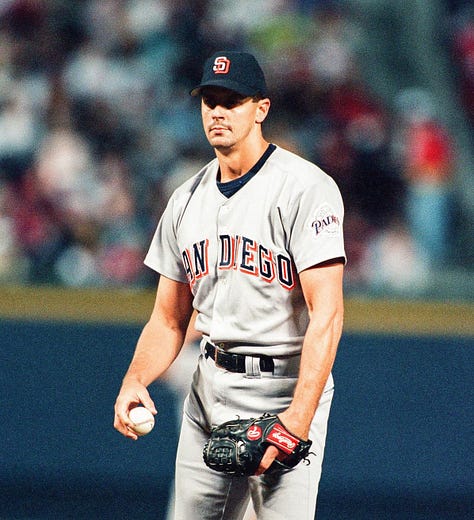

In 1998 the Atlanta Braves were in the middle of a historic playoff run and had three pitchers that received Cy Young votes, Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux and John Smoltz. Glavine was the winner of the award that year but I think there were to other pitchers that would have been better choices.

Maddux and Padres pitcher Kevin Brown. Glavine finished the season with a record of 20-6, an ERA of 2.47, four complete games, three shutouts, 157 strikeouts and a WHIP of 1.203 in 229-1/3 innings. Brown finished with a record of 18-7, an ERA of 2.38, seven complete games, three shutouts, 257 strikeouts, and a WHIP of 1.066 in 257 innings. Maddux was 18-9, an ERA of 2.22, nine complete games, a league-leading, five shutouts, 204 strikeouts and league-leading, a WHIP of .980 in 251 innings. In fact neither Brown or Maddux was even second place, that went to Padres closer Trevor Hoffman (this was pre-2003), who pitched more than 125 innings less than all three of the starters. This appears to be the 20 game winner scenario, because that is the only stat that Glavine led in.

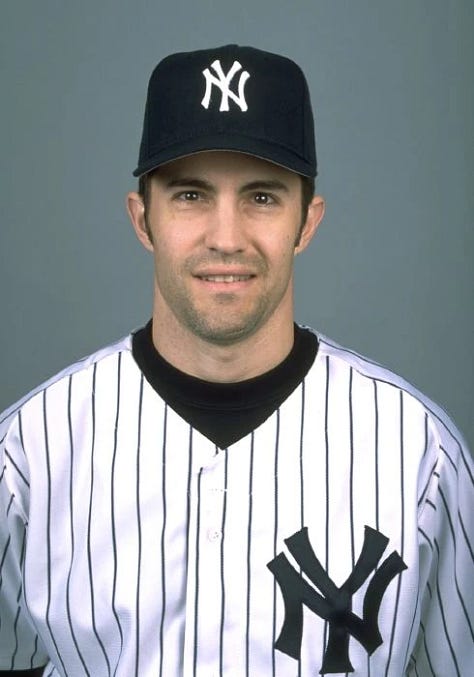

In 2001, Yankees fire-baller Roger Clemens won his sixth Cy Young award with a 20-3 record, a 3.51 ERA, 213 strikeouts and a WHIP of 1.257 in 220-1/3 innings. However, there were two other pitchers who many thought were more deserving of the award and Clemens might not have even been the best pitcher on his team. Right-hander, Mike Mussina had a 17-11 record, with an ERA of 3.15, 214 strikeouts, four complete games, three shutouts and a WHIP of 1.067 in 228-2/3 innings of work. Oakland A’s lefty, Mark Mulder was 21-8, with a 3.45 ERA, 153 strikeouts, six complete games, four shutouts and a WHIP of 1.156 in 229-1/3 innings.

Maybe you discount Mulder because his strikeouts are so much lower than Clemens or Mussina’s but he did lead the league in shutouts. However, both Mussina and Mulder had lower ERAs, and better WHIP than Clemens in more innings. You can’t say it was the magic number of 20 wins, because Mulder had 21. You can’t chalk it up to East Coast bias because Mussina was also a Yankee. I think this was given to Clemens because he already had five had the writers wanted him to keep the title as having the most ever, with Randy Johnson in the National League winning his fourth that same year.

In 2003, LA Dodger closer Eric Gagne had a historic season, a league-leading 55 saves without a blown save, an ERA of 1.20 and a WHIP of .692 in 82-1/3 innings pitched. That performance earned him the Cy Young from the writers. However, he was a closer, a pitcher that hardly ever pitches more than one inning a game. There were two other players that would have been better picks to win in 2003. The first, Giants right hander Jason Schmidt was 17-5 with a 2.34 ERA, three shutouts, five complete games, 208 strikeouts and a WHIP of .953 in 207-2/3 innings.

The other, was Cubs starter Mark Prior, who was 18-6 with a 2.43 ERA, one shutout, three complete games, 245 strikeouts and a WHIP of 1.103 in 211-1/3 innings. One could quibble about whether Prior or Schmidt had a better season, but I think that it is undeniable that both were a better choice then Gagne that year. After the uproar over this pick, it is unlikely any closer ever wins a Cy Young again. The argument is similar to that over if a pitcher should win a MVP when they only play every fifth day. A closer pitches appears in games much more often than a starter, but it is only two innings, tops. In the 2003 season Prior pitched 129 innings more than Gagne, and Schmidt threw 125-1/3 more.

The 2005 AL Cy Young award came down to three pitchers. Bartolo Colon from the Angels, Mariano Rivera of the Yankees and Johan Santana from the Twins. The award went to Colon, mostly because he won 21 games. Santana was superior in every other category. He had an ERA of 2.87 compared to Colon’s 3.48. Bartolo had two complete games to Johan’s three, two shutouts to Colon’s zero. Santana pitched more innings, gave up less hits, less runs, less homeruns, and less walks.

Santana also had 81 more strikeouts (a league-leading 238 to 157), and had a WHIP of .971 compared to Colon’s 1.159. The only good thing about this vote is that I can say that my spirit animal, Bartolo Colon, won a Cy Young Award. Rivera lost out because he’s a closer and after the controversial 2003 pick, the voters had a hard time voting for a pitcher that only throws one inning a game, even if he did have a pretty good year. I’ve included a bonus video of Bartolo being Bartolo, Enjoy!

Here is a good place to stop for this post. Next time I’ll wrap up my examination into the horrible track record of the Baseball Writers Association of America have in picking players for awards and induction into the Hall of Fame. Specifically, Rookie of the Year awards, Hall of Fame snubs and the steroid controversy. I know I threw a lot of stats at you but you can’t really talk about this issue without looking at them. I hope you have enjoyed this post or at least found it educational. Please feel free to pass it on to anyone who might find it enjoyable or entertaining.

Chris

OBP is On Base Percentage, it measures the number of times you reached base, via a hit, walk or being hit by a pitch. It is calculated by dividing the number of times you reached base by at bats, walks, hits, hit by pitch and sacrifice hits. The average in MLB history is around .315.

SLG is Slugging Average, it measures how much power you hit with it is calculated by adding the number of bases you get in a season 1 for a single, 2 for a double, 3 for a triple and 4 for a homerun divided by your at bats. The average in MLB history is .385.

In 1925, the eight AL cities were Philadelphia, St. Louis, Washington, Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, New York and Boston.

The hitters Triple Crown is awarded to the player that leads the league in batting average, homeruns and RBIs. In the Modern Era of baseball (1900-present) 15 players have won the Triple Crown.

The most wins for a pitcher in a single season is Denny McLain in 1968 for the Tigers when he won 31 games. ERA stands for Earned Run Average. It measures the number of earned runs (doesn’t count runs scored because of an error) a pitcher gives up in nine innings. The lowest ERA since 1900 is 0.961 that Dutch Leonard put up for the Red Sox in 1914. The most shutouts in a single season is 16 by Grover Cleveland Alexander for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1916. The most innings pitched in a single season is the 390-2/3 by Christy Mathewson for the New York Giants in 1908. WHIP stands for Walks and Hits per Innings Pitched. It measures how many walks and hits a pitcher gives up every inning they pitch. Hit batsmen, errors and hitters who reach via fielder's choice do not count against a pitcher's WHIP. A WHIP of 1.00 is considered elite. The modern record for a single-season WHIP is held by Pedro Martinez in 2000 when he registered a WHIP of 0.7373.