Last time I wrote about my my first two months in Somalia and what I experiences as a Marine on the ground. Click below if you missed it.

Today I’ll be continuing my recollection of my time in Somalia. It is a very interesting story, I hope you enjoy it.

Apprehension

As the days on the calendar changed, a feeling of dread would creep a little closer to the surface of my mind. My fear was that the mission in Somalia would not be completed before my enlistment was up. I was scheduled to leave the Marine Corps on May 30, 1993, but since the end of the Vietnam War, the Marine Corps has had a policy of not discharging Marines if their enlistment came up while they were deployed.1 The official term for that situation is Involuntary Extension, in other words, if that was what happened, I would remain in Somalia until 3/9 and 3/11 left the country, no matter how long after my enlistment that was. That was the same reason I had been transferred from 3/7 to 3/11, I didn't have enough time to go on the six month deployment 3/7 was preparing for. Of course, I had absolutely no idea how long the mission would last, and there were no discernable goals to measure success against. I also didn’t know how long the Marine Corps would wait to make the decision to extend my enlistment. I didn’t know if they would do it in March or April or wait until May 29 to tell me, “sorry you’re stuck here until the end, hope you didn’t have any plans.”. The latter seemed the most likely to me, because it just seemed like something like Marines would do.

Vehicles, vehicles everywhere and not a one to drive

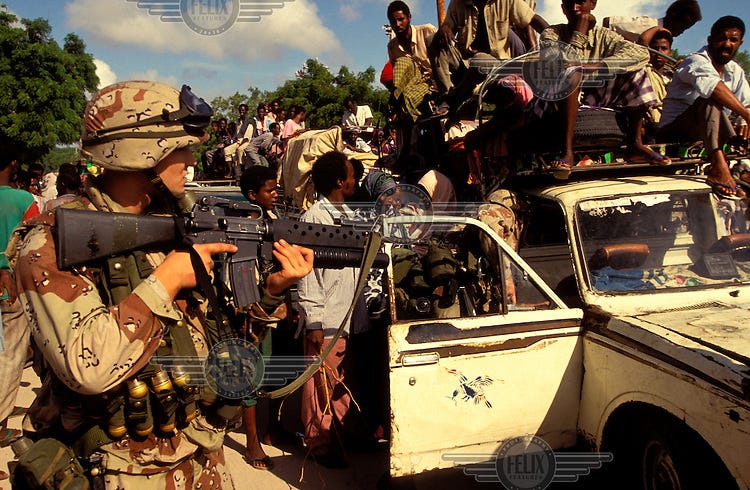

I never liked checkpoint duty, it was long, boring, dirty and dangerous, but it was a task that was considered vital to the disarmament effort and the overall mission, therefore, had to be done. Every day there would be multiple checkpoints set up across the city, stopping cars and searching for weapons.2 All the cars, especially the Somali-owned ones were rusty, broken, dusty and dirty and we had to paw through them looking for weapons. Whether we found them quickly or not depended on who owned the car. If it was an NGO or other official group, then the weapons were usually in plain view or in easy reach, and while they didn’t want to give them up, they understood what we were trying to do, and agreed with it, at least in principle. The same could not be said if the Somalis themselves. They never seemed to understand why we had to take their weapons and resented it every time. If the vehicle was owned by a “good” Somali the weapons could be in plain view or not very well hidden. If they were part of one of the factions, the weapons could be much harder to find, think hidden compartments, drug smuggler kind of thing. There were vehicles that we had to almost completely take apart to find the weapons, and if the occupants complained too vigorously, they would be arrested. Those ones were the most dangerous stops, because they might have friends nearby looking at you through rifle sights. There were a few incidents where Marines manning roadblocks were shot at while searching cars but no one was ever wounded, and it was added to the list of inconveniences suffered through during our time in Somalia. It did make things interesting for a while though, everyone, including the Somalis, would hit the dirt and the Marines would look for the shooter, we would hardly ever see anyone and after a few shots it would all be over and we would return to the task at hand.

However, not every country that sent troops to Somalia had the same rules of engagement as us, and one time I saw that first hand. My platoon was working a roadblock with a platoon of soldiers from Botswana, we were several hours into it, with everything going swimmingly, when all of a sudden we heard the crack of rifle fire, and the whine of rounds as they screamed by. Everyone hit the dirt except a few of the Botswanans who ran to their armored car, maned the turret equipped with two machine guns, one .50 caliber and one .30 caliber. They opened fire on the buildings where the fire came from, with their fire totally shredding the front of the buildings, and starting of few small fires. No one checked to see if the sniper had been killed, or if anyone else had, for that matter, but we didn’t receive any more fire the rest of the day. So, they either got him or scared him away. After the Botswanans ceased fire, everybody just got up and carried on with their day, like nothing had happened. It was a little off-putting to see so many people seemingly so comfortable with violent military action.

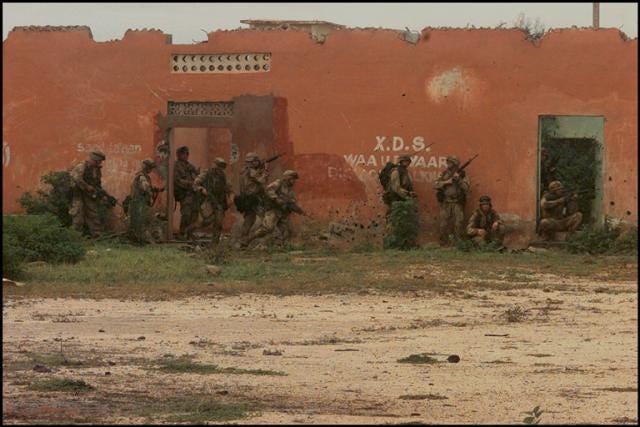

Operation Cobra

On January 7, 1993, while I was still with 3/9, I was involved in an attempt to secure military equipment belonging to General Aidid. There had been an incident the day before, where a Marine patrol had been fired upon near a known storage area for weapons and vehicles belonging to Aidid. At the time the equipment was permitted to be in storage but could not out on the streets. There were no casualties, but the exchange prompted UNITAF command to inform General Aidid that the area would be seized by Marine forces and it would be wise for his men to surrender peacefully. I was actually part of the security force that escorted the UNITAF brass to General Aidid’s house, and I know that I wasn’t the only Marine present that would have been glad to take out the man responsible for the majority of violent incidents in Mogadishu. That wasn’t the plan the brass had, so the message was delivered and we prepared to capture the base the next day.

When we got on the road early in the morning, it was as part of another large force, this time accompanied by M1A1 Abrams tanks and AH-1 Cobra helicopter gunships overhead. We surrounded the compound, including putting snipers on nearby buildings. An order giving the men inside ten minutes to surrender, was broadcast by bullhorn, in both Somali and Italian.

As a radio operator I was clued into things that the regular infantry didn’t know, including that a 20mm anti-aircraft gun was sitting in the middle of the compound, making the Cobra pilots very nervous. After the ten minutes was up, one last broadcast was made, informing them to surrender now or we would take the compound. The snipers reported that two men were running towards the anti-aircraft gun, the task force commander Colonel Peck, (I looked his name up), told the snipers “if they touch the gun, take them out”. A minute later there were two shots and the snipers reported that both men were dead.

This started a general firefight with the Marines standing on the hoods of Humvees and the hulls of the tanks to be able to fire over the wall into the compound. Each Cobra made a run across the compound from different directions firing their 20mm rotary cannons, adding to the smoke and overwhelming noise of the action. The Somali fire was mostly wild or directed towards the Cobras. After 15 minutes Colonel Peck ordered the tanks to blow a hole in the wall surrounding the compound, allowing us to enter the base. When we got inside, the remaining Somalis quickly surrendered. There were no US deaths and a few Marines were lightly wounded, I never heard how many Somalis were killed or wounded. We captured a large number of weapons and ammunition, along with three M-47 Patton tanks and a half dozen technicals.

You would think a large seizure of weapons and a public and decisive defeat like the raid on Aidid’s compound would have some kind of effect on the situation in Mogadishu, but it didn't make a dent in the violence at all. Everyday, for the rest of January and the beginning of February, 1993, we would conduct patrols and setup our roadblocks. We would confiscate all the unauthorized weapons we found, and make small seizures of weapons and ammunition here and there, but the situation didn't really change. It was like a game of hide and seek for the Somalis. We would search an area, and the day after we were there, the militants would move weapons from a different area of the city where we were about to search into the area we had just left. I'm sure that they were being given information about the sweeps by Somalis working for UNITAF. Remember clan affiliation overrules ever other concern, and what better way to help you clan than to given them information that could save vital weapons from seizure by the Americans.

After the seizure of the Aidid compound, the level of support enjoyed by UNITAF from the average Somali citizen was at it’s highest, as it became evident that US forces were not going to play favorites and were there to actually make a difference. However, the attitude of Aidid’s and Ali Mahd’s forces continued to harden when they discovered that they were not going to be able to conduct business as usual. They had come to enjoy being in control and even though the situation was less than ideal, it was better for them than being one of the people begging in the streets. It took some time and a few violent clashes with the Americans for Aidid and Ali Madhi to realize that the US wasn't the paper tiger that the UNISOM forces had been. The militants were used to being able to intimidate and harass UNISOM into inaction, which allowed them to dictate the pace and location of food distribution and artificially extend the famine after it should have ended. UNITAF spent many hours trying to negotiate with both Aidid and Ali Mahdi to end the interdiction of food convoys into the interior and during that period of the US involvement. I’m sure both men were told that as soon as they stopped interfering with the convoys, the US would leave. These negotiations involved many visits between UNITAF officers and Aidid and to a lesser extent Ali Mahdi, and I was part of security for a few of the visits to Aidid's compound. If the US had known then what they would learn in October of 1993, maybe one of those visits would have been to arrest or kill Aidid, history would have been different and 18 Americans would still be alive.

Khat Time

Every now and then a vehicle would try to run a roadblock, which was never a good idea, because it almost always resulted in the deaths of the people inside the vehicle. Sometimes the dead would be fighters from one faction or another attempting to move weapons around the city, other times it was just someone that panicked or was under the influence of the most popular drug in Somalia, khat.

The khat plant is native to the horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula and contains the alkaloid cathinone. When many, many, and I mean many, of the leaves are chewed, the user feels greater sociability, excitement, mild loss of appetite, euphoria, mild mania, as well as increased blood pressure and heart rate. Every day, Kenyan and Ethiopian farmers pick a huge amount of khat leaves which brought in $400,000 a day to the farmers. When I was in Somalia 15 cargo planes full of khat arrive in Somalia each day, where the leaves are promptly sold before they lose their potency.

The leaves are chewed by men, up to 80% of men in Somalia, for a few hours in the midmorning. Each person needs to chew over half a pound a day to receive the effects. Around 1:00 pm all the men chewing the leaves would become agitated talkative and aggressive, it became known as “khat time”, and it is when most of the sniping and other violent incidents occurred. A few times while manning roadblocks I saw a group of Somali men sitting against a wall, each with a large bag of khat, patiently chewing the leaves. After a few hours, they would suddenly start talking very quickly, gesticulating wildly, running around, getting in the way of what we were doing and making a general nuisance of themselves. If younger men were involved, there could be trouble, especially if they were armed, that's why the disarmament effort was so important, it frequently prevented real violence. That was “khat time” and it would happen all over the city, every day around the same time. It would last about two hours and then everyone was back to normal until the next day.

Our International Partners

As I said in Part I there were 23 other countries that had sent forces to Somalia, they all were different sizes and had different missions. Some were medical units, others were intelligence units. Germany, for example, sent three aircraft that transported supplies from Kenya. All these forces had different rules governing their action, even though they were all under the command of the US. like I mentioned earlier, the Botswanans3 did not have the same rules of engagement as we did. It was also perfectly acceptable for the Italian contingent to shoot into the air to scare away crowds that gathered anywhere UNITAF forces stopped. The attitudes of the foreign forces was also varied. The western countries view the Somalia as victims that needed to be saved from a horrible situation. The Middle Eastern countries viewed the mission as a way to help fellow Muslims as well as a way to garner Western goodwill, but it was the African countries that had the strongest reactions to the situation in Somalia. When I say African countries I mean the sub-Saharan countries, Botswana, Nigeria and Zimbabwe plus Ethiopia. Those countries viewed the existence of Somalia in it's current state as a personal insult to all of Africa. Those four countries had been working very hard to mold themselves into respectable countries that, while not entirely self-sufficient, were making strides in the right direction. Plus, Ethiopia had fought a war against Somalia in 1977, so there was a personal element to it for them. All of these countries viewed Somalia in it's current state as a insult to the dignity of their countries and Africa herself. They all took very hard stances against any kind of militant activity, and would come down hard on any violence directed against them. There were multiple complaints by Somali civilians against their tactics, but they also didn't have as many violent incidents against them and we all appreciated it, when they were around. Because they could act in a way and do the things we wanted to do, but could not.

Operation Metal Snake

As we moved around the city, there were masses of people out and about, but what they were doing was kind of a mystery. As far as I could tell the economy of Mogadishu largely revolved around two things; 1. selling flattened five gallon metal cans, and 2. selling charcoal. The cans had once contained relief supplies like olive oil, water or milk and were used by the residents of Mogadishu to repair their houses, and by the refugees to construct hovels to live in. I don’t know what they were doing with the charcoal, but there were a lot of people selling it. When I say selling, I really mean bartering, because the Somali Shilling was worth so little, there were literally billions of shillings worth of paper money blowing around the streets. The charcoal sellers even used them to start their fires. That is the another smell I remember from my time there, the smoke smell from the charcoal fires. If I smell a campfire, even now, the smell of death is brought up in my mind, they go hand in hand.

There were a few people trading clothes and other items in the city, but food for sale was scarce. There was a large bazaar in central Mogadishu, called the Bakara market. Unfortunately for all the hungry and starving people of Mogadishu, there wasn’t much food for sale. Instead, the market was Somalia's biggest arms market, known as the Kmart of Kalashnikovs. According to intelligence reports, tens of thousands of pistols, rifles, machine guns, grenades and even artillery pieces were thought to be hidden in market's warren of narrow alleys. I was one of the 1,000 Marines sent into that horrible place on January 10, 1993, to look for those weapons, and it is another story that will stick with me forever.

Danger! Profanity Ahead!

It was crowded, hot, smelled bad, and very claustrophobic in the market. We were all on edge because we were told to expect resistance to the sweep. I was also saddled with the 17 pound radio and the ten foot tall antenna, in an attempt to maintain good communication during the operation. The Somalis had put up corrugated metal sheets over the narrower alleys and my antenna would not fit unless I walked bent over at the waist. We didn’t find any weapons in our area,4 but I did see a few goat heads hanging from hooks covered in flies, the extent of the “food” available. At the end of that row of stalls there was a small doorway into another area of the market. I didn’t see it in time and my antenna got stuck on the frame of the door, bending me backwards. At the time, the lieutenant, who was in front of me, was talking on the radio, and the handset cable was stretched as far as it could go, over my shoulder to his ear five feet away. When I got stuck he started pulling on the cable. Meanwhile I was trying to straighten up, get the antenna unstuck and at the same trying to move closer to him to keep anything from breaking. This actually caused the antenna to become even more jammed in the doorframe. Eventually, the antenna broke and at the same time he gave a good yank on the cable and I came flying out of the doorway. The lieutenant, who was completely oblivious of all my shenanigans, had taken a little path to the left after coming out the doorway, because directly in front of the door, there was a huge cesspool of indeterminate depth and composition. I, on the other hand, had no real control over my trajectory and landed right in the middle of that stinking hole. I sank up to mid-thigh in god knows what and I WAS MAD! I slammed my helmet down on the edge of the hole and cursed the lieutenant out.5 I yelled: Goddammit, sir, look what you fucking did, what were you fucking thinking pulling on the Goddamn cable like that, if I get some kind of disease from this fucking shit hole, it’s your fucking fault sir. The other thing that saved me from getting in trouble was the fact that he knew he screwed up. Not only did he pull me into the cesspool, but he also broke our antenna, and he would have to explain why to his boss when he asked for another one. A few Marines pulled me out, it was not easy, I was really stuck in there and they were trying to do it without getting pulled in themselves. When I got out I was covered in crap and who knows what else. It was in my boots, I could feel it between my toes and I was trying not to think about what I was covered in, and throw up. The rest of the day no one would stand anywhere near me because I stank. when we got back to the stadium I immediately changed, took two showers, and burned those socks and pants. The pair of boots I was wearing was broken in and I had not worn my other pair at all and I wasn’t about to add blisters to my list of complaints. So I had to clean them up as best I could, and moved on.6 I did start wearing the other boots in small increments to start the break-in process but the first pair was my go to pair most of the time. Just like after the raid of the Aidid compound, this raid did not make a lick of difference in the overall security situation in Mogadishu. We still found just as many weapons as before and the number of sniping incidents did not decrease.

The City of Death

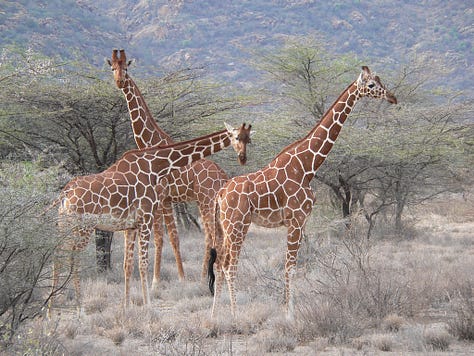

Around this time I got a chance to be part of the security element for a convoy going into the interior of Somalia, and I jumped at the chance. I was eager to see something other than the city. The convoy was a UN-run one using African trucks, (not US military truck), driven by “friendly” Somalis, going to Baidoa a city 140 miles from Mogadishu. Known as “The City of Death”, it was where the impact of the famine was at its worst. As I said, it was only 140 miles away, a two hour, twenty minute drive in America, but here, where the roads were 100% worse than anything you have ever seen, and only being able to travel as fast as the slowest vehicle, it was going to be a sixteen hour round trip (at least that was what were we told). We started off at 6am and didn’t even get out of Mogadishu before we had the first truck break down. It took an hour to get it running again, which was a very tense time for us, since we were guarding 20 tons of grain and it would have been quite a battle to keep it safe if the militants had run across us. As we got outside of the city I saw miles of wheat and corn fields, as well as banana and orange groves. Food that was being prevented from getting to the people that needed it because of clan conflict. I also saw real African animals, herds of zebras, giraffes, antelope, gazelles and the African wild ass (Free the Donkeys of Somalia!), lots of wild camels and even a few elephants.

After at least five more truck breakdowns, and a total of twelve hours, we finally arrived in Baidoa. The City of Death made Mogadishu look like a paradise and smell like a perfume factory. This is where most of the people were starving to death, I saw walking skeletons holding the hands of skin and bones children, waiting in line for a sorghum-based gruel to keep them alive and maybe give them a little extra nutrition. I saw people just sitting around, and it was hard to tell if they were alive or dead. Since I knew that this situation was exacerbated by the actions of their fellow humans, it was quite depressing. It is something that has stayed with me ever since, and it is a one of the reasons I’m so cynical regarding the “innate goodness of humans”. The normal population in 1993 was 293,000 but there must have been at least 600,000 people crowded into the city. Refugees from areas to the northwest and southeast were everywhere and here the people were dying so fast that there wasn’t even time to pile dirt over the bodies.7 The smell in Baidoa was beyond description , so much worse than Mogadishu. It made me wonder how the people working for the UN and the charities could even stand it. The trucks were quickly unloaded and the convoy returned to Mogadishu. There were only two breakdowns on the way back and it only took us ten hours. The trip was like going to another world, and not a good one. I’m glad I wasn’t with the Australians or 2/7 since they were there all the time.

Not long after returning from Baidoa my time with 3/9 was over, and since that is a great place to stop, so will this post. Next time I will continue with my Somalian adventure. I go back to 3/11 and then get a big surprise, to finish up my time in Somalia. As I said last time, this is harder than my normal posts to write, since I was directly involved in the events recounted here. I hope you are enjoying this more personal writing and are look forward to the next part.

Chris

Letting people end their enlistment while deployed, meant either the unit would be shorthanded or would find itself training new arrivals in a less than ideal situation, maybe even in a combat zone. The Marines found it was detrimental to unit morale and effectiveness.

If you remember from Part II a system of passes was in place that allowed NGOs and other official agencies to possess a weapon. One pass equaled one weapon.

I don't know if the Botswanans hand picked their soldiers or if they just had a certain type of man that joined their army, but all the soldiers looked like they were NFL linebackers. Every one of them were about 6’3” and weighed around 250 pounds.

In other areas of the market, two tons of weapons and ammunition were seized.

You can do it, as long as it isn’t personal and you put “sir” at the end of it.

The only reason I was able to change was I had been to Desert Storm. In preparation to our deployment to Somalia, we were issued one pair of desert camo utilities, but because I had the pair I was given for Kuwait I was able to wear them. They were a different camo pattern, and I stood out from the other Marines in 3/9 but that was kind of fun.

According to the UNHCR over 1,000 people were dying every day in Baidoa and 74% of children under the age of five living in the refugee camps died. The main causes of death were diarrhea and measles, which are preventable infectious diseases.