Operation Restore Hope Part II

The sights, sounds and smells I experienced as a Marine in Somalia, during the early stages of Operation Restore Hope.

Last time I examined the history of Somalia, the timeline of the UN relief efforts and the US involvement. Click below if you missed it.

Today I will talk about what I heard, saw and did in that troubled country.

Note: Just a word of caution, this is a post about Marines therefore there are more than a few curse words in this post and two sections where quite a few four letter words are used. If you are offended by those kind of words please skip those sections.

Note: None of the pictures in this post were taken by me. I was still in infantry mode, and any non-essential items, such as cameras, were left behind.

Note: I’m fuzzy on my timeline while in Somalia, other than important dates I can look up, like when I arrive, when I left and President Bush’s visit. The names of the Marines I served with in Somalia have faded, it was 31 years ago after all, and I wasn't with them for very long. Especially the people in 3/9, I was only attached to them for around two months.

In October of 1993, the local paper in Traverse City, Michigan, the Record Eagle, interviewed me for a story they were doing regarding the Battle of Mogadishu. For those of you too young to remember, that was an incident that occurred during the Somali Civil War (1990-2012), just after Operation Restore Hope, specifically during Operation Gothic Serpent on October 3-4 1993, where Somali gunmen shot down two Blackhawk helicopters with rocket propelled grenades, and the US fight to get the survivors out. When the smoke cleared, 18 Americans were killed, and 73 wounded. The lasting image from the debacle was of Somalis dragging the bodies of American servicemen through the streets of a war-torn city. The country was shocked at the defeat of the US military by a bunch of fighters using whatever weapons they could get their hands on. This was just two and a half years after Americans celebrated our lopsided victory in the Gulf War, when love and appreciation of the military was at its highest. The public did not understand what had happened, and why we were still there after a successful humanitarian mission. The shockwaves of this disaster have reverberated throughout American foreign policy ever since.

The Record Eagle wanted to know what I, a Marine who had taken part in Operation Restore Hope from December 10, 1992 until April 12, 1993, thought about what had happened in the country I had so recently left, and how I viewed the role of the United States on the world stage. I told them I thought the initial humanitarian mission in Somalia was a noble and worthwhile mission, but the way the objectives had crept into nation building, was a huge mistake. As the objectives changed, so did the reaction towards American forces. What was initially viewed as a mission to help, became a mission to conquer, at least in the eyes of Somalis. At that time, freshly out of the Marines and a veteran of two combat tours, I thought that while it might be a good thing for the United States to assist countries in need, it could be unwise to stick our nose into every conflict around the world. At the same time, I also thought that the United States should use their role, as the only superpower, to make the world a better place. Even then, I knew the line between world policeman and world bully, was a fine one to walk, and I could see that there were valid arguments on both sides of the issue.

Just a little background as to how I ended up in Somalia. I spent the majority of my Marine Corps career as a radio operator with H&S Company, 3rd Battalion 7th Marines,1 one of three infantry battalions in the 7th Marine Regiment of the 1st Marine Division. In mid-April 1992, 3/7 was looking forward to a six month deployment to Okinawa, Japan, from December 1992 until June of 1993. My enlistment was over on May 30, 1993 and I wouldn't have enough time left to go with them. 2 I was transferred to an artillery unit, Echo Battery, 3rd Battalion 11th Marines. 3/11 was the artillery support battalion for the 7th Marines. I was assured that this unit wasn't going anywhere before I got out of the Marines, (I should have known better), so I went about the business of adjusting to my new unit. Oh, and I was almost sent to Los Angeles for the Rodney King riots! Unfortunately for me, as the crisis in Somalia unfolded as November ended, the 7th Marines were picked to be part of Operation Restore Hope. With 3/7 just about to leave for Japan, they were replaced by 3/9 (3rd Battalion 9th Marines). When I thought I would be “relaxing” and enjoying my last few months in the Marines, I was training and drawing gear to visit another desert. Since I had just been part of an infantry unit, the commanding officer of the communication platoon thought I would be perfect as part of a forward observer (F/O) team assigned to 3/9. As a grizzled 24-year-old, with the Gulf War under my belt, I was the matched up with two 19-year-old kids fresh out of F/O school, and we were driven to Camp Pendleton to meet our new hosts.

What I saw and experienced

After a 21 hour flight from March Air Force Base, I arrived at the airport in Mogadishu, Somalia on Thursday December 10, 1992, disembarking from an Evergreen Air 747. The airport in Mogadishu was like something out of the Walking Dead, the chain link fence was only standing in small sections, neither the terminal nor the control tower had a single intact window and both were riddled with bullet holes. There was a small burned out cargo plane sitting just off the runway and the airport parking lot was filled with looted and stripped vehicles. Even though the airport is right on the Indian Ocean with a beautiful view of the blue water and white surf, something wasn't right. A faint smell of death lingering over the city, it would be a smell I would become quite familiar with in my time there.

When I arrived in Mogadishu, the city was, to quote a famous American president, “a shithole”. There was no electricity, no working sanitation system, no police force, the roads, which were once paved and tree lined, were now broken pavement, and scattered with potholes that would swallow a car. Whole sections of the city were destroyed and nearly every house in the city sported a few bullet holes or had huge holes in them, all the windows were broken and the roofs missing (I don't understand the Somalia obsession with roofs but 95% of them were missing). The National Legislature Building, on the Somali version of Capitol Hill, had been ransacked. All the desks were broken, the fixtures had been ripped out of the walls, the carpet was missing, and it looked like someone had thought about setting the building on fire, because every piece of paper in the building had been put in a two-foot deep pile covering the entire center of the main chamber. The Somali people had also expressed their displeasure with the former government by taking shits all around the room. Just imagine the sentences that would have been handed out to the January 6th defendants if they had done this.

There were refugees from the interior of Somalia living in tin shacks in any open area of Mogadishu they could find. These were the people that were really starving, and an open field next to the biggest refugee camp was filled with the graves of their dead. They weren’t buried, just a mound of dirt thrown over the bodies. This was where the smell came from, the closer I got to it, the worse it was. It was nearly overwhelming if you were right next to it. The sickly sweet smell of death is something I will never forget. When I think about Somalia I can almost smell it again.

Somalia is the kind of place that makes you lose your faith in basic human decency. It's a place where petty clan conflicts were the driving force behind the level of crisis and the number of deaths from the famine. Those petty conflicts have shaped the people and the culture of Somalia in a way that ensures that they will never be productive members of the global community or govern themselves without significant international oversight and aid. If you remember Part I you will recall that the first president was shot over a clan dispute and those disputes colored every decision UNITAF had to make in Somalia.

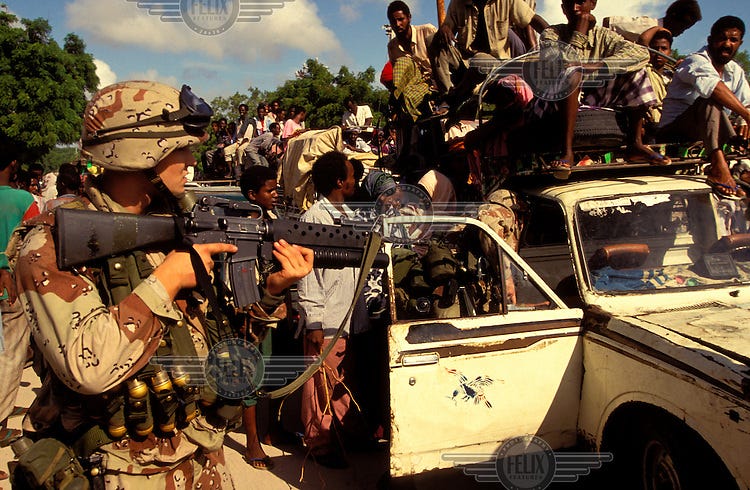

When we arrived in country, the Somalis, at least the ones not affiliated with Aidid or Ali Mahdi, were glad to see us and we were met with smiles wherever we went. That’s not to say that we weren’t shot at, in fact we were shot at nearly everyday, but it was poorly aimed fire meant more to harass us and keep us away for whatever the armed factions were doing, not fire meant to cause casualties. After a while, we became used to it and would ignore it unless it came too close. If that were the case, then we would have to respond, but our rules of engagement were so strict that we had to actually see the shooter before we could return fire. For example, if we received sniper fire that we identified was coming from a certain building, we could not fire at the building. If we wanted to get the sniper we would have to search the building to find him, and that was seldom worth the danger it presented.

After arriving in Mogadishu, 3/9 and I were initially sent to the recently re-occupied United States Embassy, which in the intervening two years, had been stripped of everything one could take, including the roof tiles (of course). The first Marine unit to arrive at the embassy, 1/4,3 raised the US flag over the embassy for the first time in two years, bringing a tear to the eye of everyone present as they did so. The flag they raised, was the flag that had flown over the Marine Barracks in Beirut, Lebanon on October 23, 1983, when a Hezbollah suicide bomber drove a truck into the building killing 241 Marines.

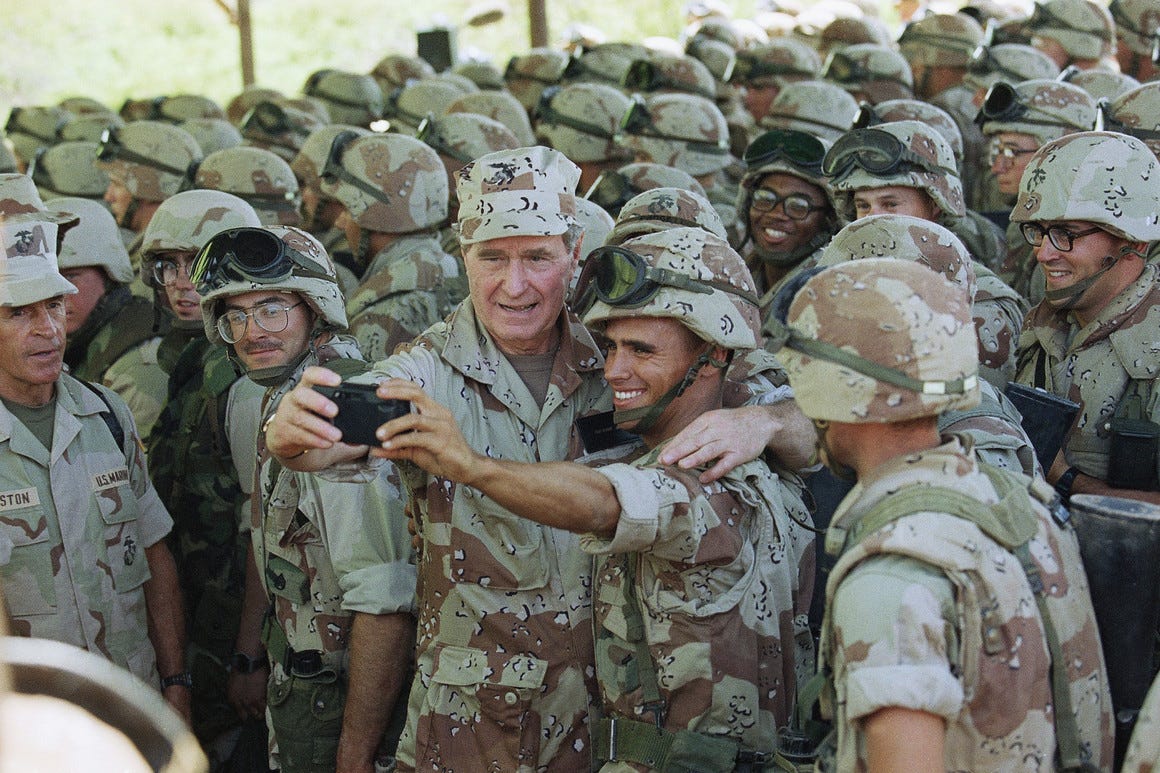

After we had been at the embassy for a week or so, we started seeing guys wearing polo shirts, with desert camo pants, dark sunglasses and earpieces. They were obviously not US military personnel, the only thing they could be was Secret Service agents. On December 30, the platoon, the Forward Observers and I, had been assigned to, were gathered together and informed that President Bush (George H.W.) was coming to Somalia to visit the troops.

We were told that we were going to be the security element for Marine One as it sat on the helicopter pad inside the embassy walls. We were informed that every other person in the embassy compound would have to remove the firing pin from their weapons, rendering them useless, but we would have operable rifles. It was explained to us that we would be facing away from the helipad watching for any threat approaching, either a disgruntled US serviceman or a Somali trying to get over the wall. We were matter-of-factly told that if we turned to see the president, we would be shot, no questions asked. We were allowed to ask question at the end of the briefing but there were only two. 1. What should we do if we see a Somali head poke over the top of the wall and 2. Who are they, the Secret Service, more worried about, the Somalis or the Marines. The answers were short and to the point. 1. If you see a head poke over the wall blow it off. 2. The Marines, and it’s not even close. The President didn’t send the Somalis here, he sent you guys. The visit went off without a hitch and none of my platoon were shot by the Secret Service, so that’s a win/win.

Because the embassy had become the UNITAF headquarters and the general security situation in Mogadishu, the compound needed to be fortified. “Guard towers” were placed at all four corners of the walls. The towers were just three Conex boxes stacked up with a window cut in one side of the top box, for either a .50 caliber machine gun (.50 cal), or a Mk-19 automatic grenade launcher. We all had guard duty in those boxes. It was hot, stuffy, boring, and noisy, it was noisy because of the Somali kids. These were local kids from Mogadishu, and while they weren't starving, it looked like they hadn't eaten in a few days. They were there to beg for food from our MREs (Meals Ready to Eat), but it was strictly forbidden to give them any.4 When we wouldn't give them food, they would throw rocks at us inside our boxes. There is nothing louder than being inside a metal box being pelted by rocks. They would throw so many rocks and they would do it so often, that we even had to put mesh over the windows to keep the rocks from damaging the weapons.

One day I was on duty in one of the boxes with another Marine and as usual there was a group of kids down below asking for food. They didn’t speak English but pantomimed eating, getting their point across. As usual we couldn’t give them any food and as usual they started throwing rock to express their displeasure. It was like being inside a bell being rung inside that metal box being as it is pelted by ten or twelve kids throwing rocks. I was leaning against the doorframe in an attempt to get some fresh air and lessen the noise, when I saw a kid pick up a rock and launch it in my direction. My baseball brain calculated the trajectory and decided that it was going to miss me, but just barely. I thought I would play Joe Cool and not move as the rock whistled by me. Unfortunately for me, I miscalculated by just a hair and the rock hit me on the right elbow, directly on the funny bone. I reacted like I had been shot, falling back into the box holding my elbow and swearing up a storm. My partner who, was surprised by my reaction, kept asking if I had been shot. I replied through gritted teeth, “no, one of those little fuckers hit me with a rock, right on the funny bone”. At that moment all I could think about was revenge, even though I knew better, and it was against the rules. I picked up one of the many rock inside the box and whipped it back at the the kid. Out of the corner of my eye, right as I let it fly, I saw the battalion Sergeant Major, the most senior enlisted man in the unit, he had caught me red-handed and I knew that something bad was going to happen to me. He screamed at me “What the hell do you think you’re doing Grenda?” I responded with the Marine version of “he started it”, but just like with parents, it didn’t pass muster. He told me to come see him when my duty was over. When I did, he chastised me again, telling me that he didn’t care how much it hurt, that was not the kind of behavior he expected from his Marines. My punishment was to take care of the heads (bathrooms) for a week. That might not sound that bad, but it was the worst things I ever did in the Marines. There was no plumbing in Somalia so the bathrooms were just outhouses, and instead of a pit underneath, there was a 55 gallon drum cut in half. So every day, twice a day, for a week, I had to haul those drums out of the four heads by hand, pour about a gallon of gas in each one, light it and stir it with a metal pole until everything was burned up. It was hot, gross, smelly work, and everyone else stayed as far away from me as they could. This was in addition to my regular guard duty, patrolling and roadblock assignments. At the end of that week I was exhausted.

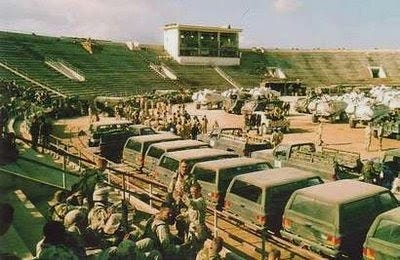

3/9 only stayed at the embassy for a short time before being moved to the rundown Mogadishu soccer stadium. We lived under the bleachers, which was nice, but had to watch out for the giant spitting cobras that also lived under there, which wasn’t. Having said that, we were bigger than their usual meals, so they left us alone, and since no one wanted to be bitten or blinded by a huge venomous snake in a Third-World country, we gave them a wide berth as well.

We ran daily patrols with the stadium as our base. Usually, they were vehicle patrols in a convoy of two or three humvees or 5-ton trucks loaded with 16 Marines each. One Marine in each truck manned a .50 cal, mounted on the roof of the cab. Most Marines did not want to be the .50 cal gunner because you are the most exposed in firefight, but I thought, if we’re going to get into a firefight, I wanted the biggest weapon available. As we drove around the city, it was my job to watch out for any suspicious vehicles or ambushes.5 As we drove through town, I would move the gun around covering likely areas for an ambush or vehicles as they approached. When I covered a vehicle, the reaction of the Somalis was always the same and made me chuckle. They would put both hands on the steering wheel and look to see how fast they were going. This is even weirder because the traffic in Mogadishu never moved very fast.

The traffic consisted of old Mercedes-Benzes, Audis, Chevy LUVs, Isuzu D-Max (both small pickups), and Toyota Hilux pickups, some of which had been turned into people carriers, (which all contained an entirely unsafe amount of people), and two wheeled carts pulled by the saddest donkeys in the entire world.

On our patrols, Somali kids would run behind our vehicles trying to get us to throw them our rations or candy, which as I said before, was against the rules, or just to see what was going on. Those kids were fast, if there was ever a 100 meter flip flop dash in the Olympics, it would be won by a twelve-year-old Somali boy. They also acted as our mine canaries, if we were driving along and all of a sudden the kids disappeared we knew we were in a dangerous area. The first time it ever happened we were rolling along and someone said “hey, where did the kids go”, a minute later, at least three guys opened fire on us as we drove by a building. We ducked behind the sides of the truck and the drivers put their feet down, getting us out of the kill zone as fast as possible. Luckily no one was hit, but we quickly learned to pay attention to what the kids were doing.

Most of these patrols were looking for heavy weapons or technicals, small pickups with a heavy weapon mounted in the back and filled with armed teenagers. They had been outlawed by UNITAF command, and we had a “seize on sight order” regarding those vehicles. This was always a risky operation, especially if the occupants didn’t want to give up the vehicle. However, we never took any casualties and captured more than a few, making everyone in the city safer.

We would also man checkpoints throughout the city looking for weapons. It wasn't hard to find them, because everyone in their right mind was armed. The difficulty was determining who was allowed to have weapons and who wasn't. There was a system in place were non-governmental organizations (NGO), or other official groups, were given a pass that allowed them to have a weapon. That being said, every car we stopped had more weapons than passes, and everyday our collection of weapons grew.

I remember one time we stopped a car from an Irish charity, there were four people in the vehicle, one pass, and six weapons, even though everyone knew the policy, they were very indignant when we confiscated five of their AK-47s. The weapons we confiscated in Somalia were the strangest bunch of misfit weapons imaginable.

AK-47s were the most common weapon, but we also found the Soviet SKS, AKM, and PPSh-41. There were World War II era US M-3 and German MP-40 submachine guns. Italian Cold War-era BM-59 carbines, Model 38 and M-12 submachine guns, Singaporean SAR-80s, German H&K G-3s, and US M-16s. We once confiscated an AK-47, that had all the original wooden parts, the foregrip, pistol grip and buttstock, removed and replaced by sky blue plastic parts. It was the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen, if Fortnite had been around then, we would have said it was the Fortnite addition. Who would do that and why would they do it?

Most of the weapons we confiscated from civilians (as opposed to the NGOs), looked like crap on the outside, super rusty and dirty, but the moving parts worked and were all very clean. Just because it looked like it had been left outside during a rainstorm didn’t mean it wouldn’t shoot you just as dead as a pristine weapon.6

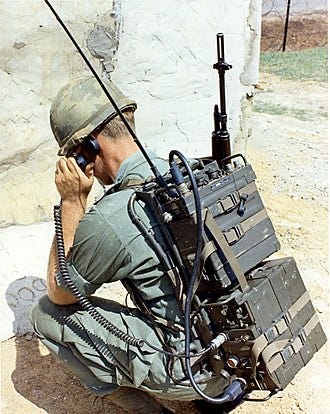

We also did foot patrols, which were considerably more dangerous. You’re walking through a potential hostile area, with no vehicle to rush you out of a ambush zone and no heavy weapons to rely on. In fact, our first casualty happened during a foot patrol. I was not on the patrol, I was the radio operator back at the stadium, electronically watching over them and their progress. They were near the Green Line in downtown Mogadishu when a sniper shot the patrol corpsman, just under the collarbone.7 The patrol commander tried to call me to get a medivac in to fly him to the hospital at the airport, but because of the buildings, and the Vietnam-era radios we used, we could not communicate clearly.8

They could receive my transmissions but I couldn’t hear them, it was garbled or static. They were getting more and more frustrated as it became obvious that I wasn’t receiving them. If this had been a vehicle patrol they would have had a much more powerful radio and would have already driven out of the area. The battalion commander sent two humvees to get them, but that was going to take a while, and we didn’t know how bad the corpsman had been hit. The situation was made that much more complicated because it was the corpsman who was wounded. All Marines are trained in battlefield first aid, but none of them had actually done it for real, with a actual man screaming and bleeding all over the place. I was beside myself, and was doing everything I could to get a hold of them. I was calling every other unit in the area, including the international contingents, in the hopes that they could contact the patrol and rely the information back to me, but that didn’t work either. After 30 minutes of trying to get through, all with a medivac on standby, the humvees reached them and the patrol was evacuated. By that time, I had been taken off the radio, because I was having a melt down and screaming in frustration at everyone. It was the only time in my Marine Corps career that I lost my composure, and it was all because I couldn’t do my job, and get the patrol the help they needed. A lieutenant took me aside and walked me around the soccer field, repeatedly telling me it wasn’t my fault, but I was inconsolable. I kept saying that if he died it was my fault. When I went back to my hooch9, the two forward observers were not helpful. All they could talk about was what they would have done if they had been on that patrol. According to them they would have charged into the building to kill the sniper and any other gunmen they found. Real John Wayne hero stuff, they obviously didn’t understand how real this was. Shortly thereafter, the humvees arrived with the patrol and the wounded corpsman himself, told me he was going to be ok, and it wasn’t my fault. The patrol commander agreed and assured me that no one felt ill will towards me. I felt relieved but was still very agitated. I grabbed his flack jacket still covered in his blood10. The round went through the front of the vest, the body of the corpsman, and almost through the back of the vest, you could feel it pushing out the back of the vest.

Danger! Profanity Ahead!

I found the young F/Os, and shoved the vest in their faces, yelling that this is fucking real life not a Goddamn movie, and here, in this fucked up place, real people get killed for fucking real. I said this wasn’t a fucking game and they better pull their heads out of their asses and get them screwed on straight before I have to stuff them in body bags. I said the rules here were different here, anyone could have a gun, anywhere and you could be shot while doing anything, at any time, then turned around and walked out of the room. The two kids were cowed enough that I never heard another comment about hero things again. The corpsman had a surgery at the field hospital and was flown to Germany for another, and to complete his recovery. As far as I know, he made a full recovery.

I’m going to stop for now, this post is already the longest I’ve had in quite a while and I still have lots to say. Next time I will finish up my involvement in Operation Restore Hope and if I have the time, I’ll tell you what I think about the operation 31 years later.

This post was difficult and different for me to write. Usually I write about an event I wasn’t involved in, and interject my thoughts between well established facts. This post was about something I lived through and something I don’t talk about a lot. It was harder than I thought it would be, to go back to that time and write about it, and how I felt. I hope you appreciate it and are looking forward to the next part of this story.

Chris

The infantry and artillery battalions names are written as 3/7 or 3/11 for brevity. H&S Company stands for Headquarters and Service Company. It was home to the communication platoon, the admin guys, the cooks, the truck drivers, the corpsman and oddly enough the snipers.

During the Vietnam era the Marine Corps would just send Marines home from wherever they were deployed when their enlistment was up. Some time after that they changed the policy, and if you didn’t have enough time left in service to complete the deployment they would transfer you to a different unit.

1/4 had made the initial seaborne landing where they were greeted by the lights and cameras of many TV stations. It was a very surreal situation.

MREs are made with very high calorie counts, around 1300 per meal, to keep us going during sustained combat. We were told that the digestive systems of the starving or malnourished Somalis wouldn't be able to be process that many calories to one time and they would go into shock.

The .50 cal was not loaded but did have a ammo box hooked up and all I had to do was open the receiver and slap the ammo belt in there, close it, pull the charging handle and I was ready to fire.

If you’re wondering what happened to these weapons, it might surprise you to learn that they were dumped out of a helicopter into the Indian Ocean. There could be a large reef, just off the coast, home to a large variety of sea life, built on a foundation of those weapons. If that is the case. it might be the best thing we did there.

Marines don’t have their own medical services, we rely on the Navy to provide them. Every battalion has a platoon of 20 Navy medics, known as corpsman. They are beloved in the Marines, because they will do all they can to help an injured Marine, even at the risk of their own lives.

The PRC-77 radio that was the man portable radio of the day had a theoretical range of three miles with the three-foot tape antenna and five miles with the ten-foot whip antenna but those needs to be taken with a mountain of salt. The range depended on a variety of factors; terrain, weather conditions, battery strength, and other electromagnetic energy present (other radios nearby) are the most common.

A hooch is military slang for the place your living/sleeping while in a camp on deployment. It could be anything from a pup tent to a sandbag bunker or a few poncho spread over the ground with overhead cover like we had.

At the time, the protective vests issued to the US military were not meant to stop a rifle round, or a close range pistol round. They were designed to stop shrapnel from artillery shells, mortars and hand grenade fragments. The same goes for the helmet we we equipped with. They were both hot, the vest weighed nine pounds, and everyone hated them.