Operation Restore Hope Part I

The first in a series examining the role of the United States on the international stage in the 20th century and beyond.

Last time, I posted about modern Islam’s seeming lack of concern for the history that came before them, as well as their continual denial of that history, especially by the Palestinians. Click the link of you missed it.

Today I will talk about a question that has plagued the United States since the founding of the country, but especially since World War II: what role should the US play in the world today, or to put it another way. Should the US be the world's policeman?

Recently Bari Weiss and the Free Press had a debate on this question. You can listen to it for free on the Honestly podcast, wherever you get your podcasts, I would recommend that episode and the podcast as a whole, she always has interesting guests even if you don't always agree with them, (Bari, I'll take a gratis month on my Free Press subscription for the plug). On the side of the US continuing its role as the world's policeman was Brett Stevens and Jamie Kurchick, on the side of having America abandon the role of policeman was Matt Taibbi and Lee Fang. Throughout the debate, which is very entertaining and thought-provoking, all four men reiterated that they had never served in the military, and that was impacting their opinions. Click this link to read the article and watch the video of the debate. Well, I’m a former Marine and a student of history, and I also have thoughts on this issue. As they said it’s not a simple question and the answer, which can be very nuanced, changes frequently, even in my own mind. To set the stage, I will examine my personal brush with this question, Operation Restore Hope in Somalia. I will set the scene in Part I, by looking at the history of Somalia, the short-lived democracy, the situation that led to the UN intervention and the US involvement. In Part II, I will relate my personal experiences in Somalia.

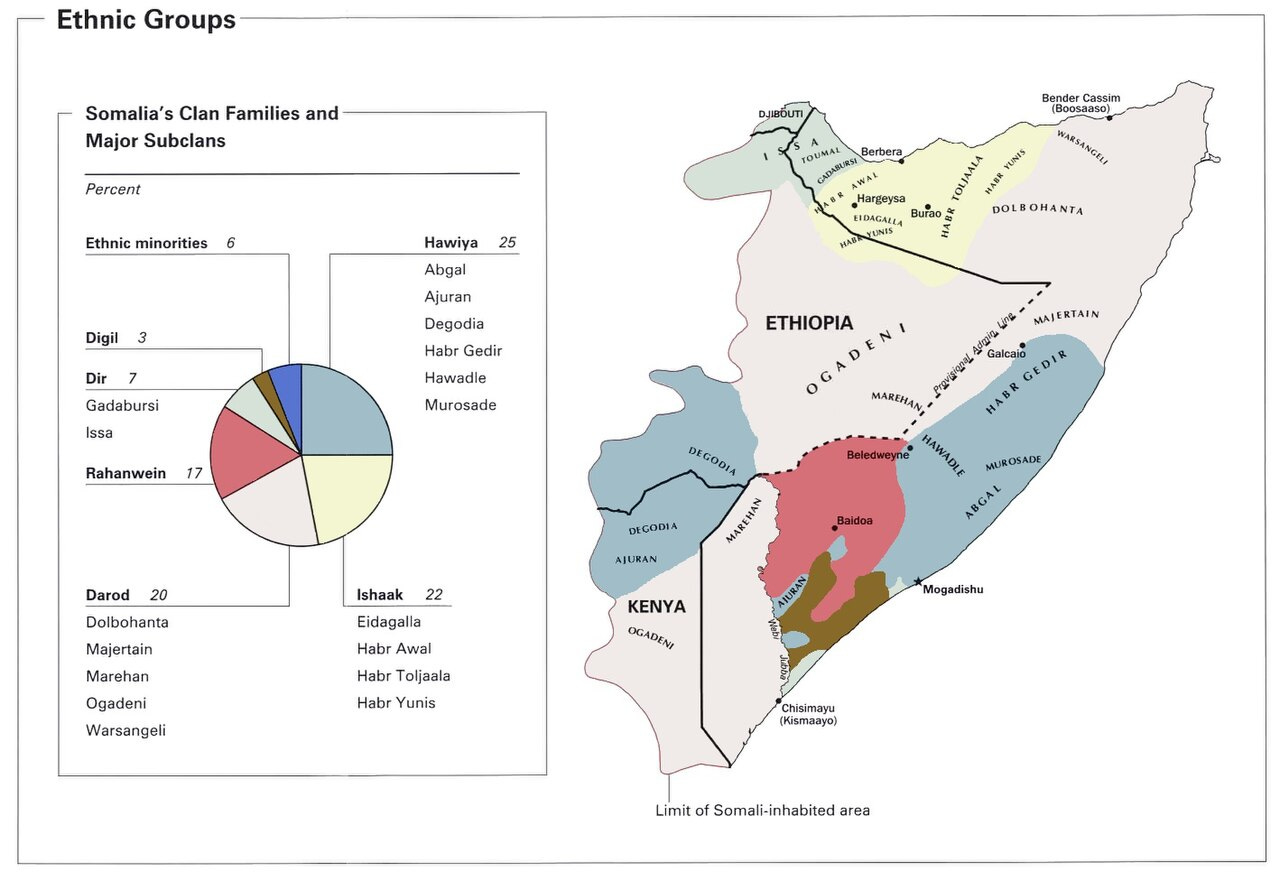

Everything you didn’t want to know about Somali clans

The most important aspect of Somali society, and perhaps the most difficult for Western observers to understand or appreciate, are the concepts of lineage and clan affiliation. It is no exaggeration that Somali children are taught their lineages for several generations back, so when they meet another person, each can recite his ancestry and thus understand his obligations and responsibilities to the other. Traditionally, all Somalis trace their ancestry back to one man, Abu Taalib, an uncle of the Prophet Mohamed. His son, Aqiil, in turn had two sons, Sab and Samaal. It is from these two the six clan-families descend and through which all ethnic Somalis trace their ancestry. The Sab branch is represented by the Rahanweyne clan, while the Darood, Dir, Issaq and Hawiye are descended from Samaal branch. Over generations, each of these clans were further subdivided into sub-clans and sub-sub-clans. If you ask a Somali who he is, he will tell you what sub-clan and clan he belongs to, not that he is a Somali or even where he is from. Clan structure and interactions are so important that I received a extensive briefing on the subject before I deployed there.

Major Somali clans:

Dir- 7% of Somalis are members of this clan. Gadabursi, and Biymaa are the most prominent sub-clans in the Dir family. Khadija Qalanjo, a popular singer in the 80s, and Ahmed Shide, the current Somali Minister of Finance are notable members of the Dir.

Rahanweyn- 17% of the population are members of this clan, with Mirifle and Digil being the largest sub-clans. Notable members include Adan Mohamed Nuur Madobe, speaker of the lower house of the Somali Federal Parliament, and Abdulkadir Mohamed Nur the current Minister of Defense.

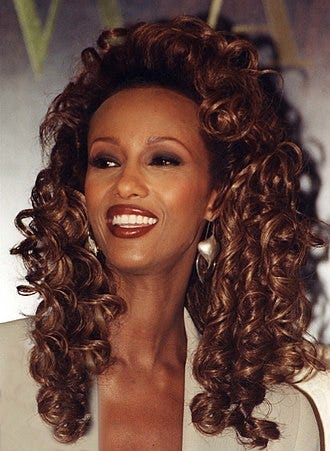

Darood- 20% of Somalis belong to this clan. The largest sub-clans inside the Darood are: Majertain, Ogaden, Marehan, and Harti. The third President of Somalia, Siad Barre, as well as model, and wife of David Bowie, Iman, are notable members.

Isaaq- 22% of the population belongs to this clan and Issa, Arap and Gadaburs are the largest sub-clans in the Isaaq family. Notable members include Edna Adan Ismail, first female Foreign Minister of Somaliland (a disputed area in the north of Somalia), and Mohamed Sultan Farah, Sultan for the Arap sub-clan, and the first traditional leader to join the Somali National Movement.

Hawiye- At 25% it is the largest clan. The biggest sub-clans are: the Habar

Gedir and the Abgal. Fourth President of Somalia, and former warlord Ali Mahdi Muhammad and Mohamed Farrah Hassan Aidid, warlord and self-proclaimed president of Somalia, are members of this clan family.

A thumbnail history of Somalia

According to the fossil record, Somalia has been inhabited for at least 50,000 years. Most historians believe that Somalia was the Biblical land of Punt. However, Somalis have a different view of their troubled country. They say that when God created Somalia, He laughed.

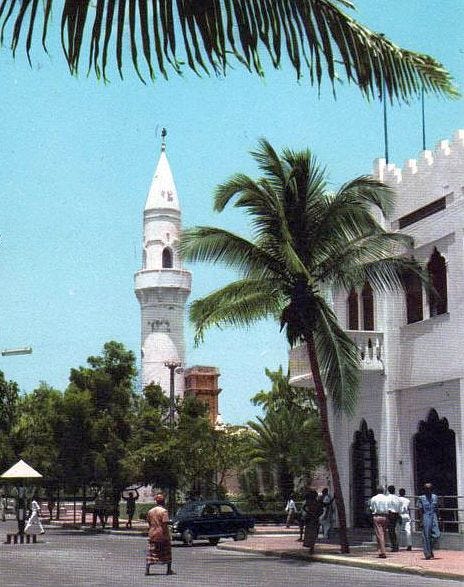

Islam came to Somalia around 615 AD in the First Hijra where the original followers of Muhammad migrated from Arabia because of their persecution by the ruling Arab tribe, the Quraysh. They were granted refuge in the Kingdom of Aksum, a Christian state located in parts of modern-day Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia. The Masjid al-Qiblatayn mosque in the town of Zeila, dates to the 7th century, and is the oldest mosque in Africa.

After the Berlin Conference in 1884, the European power began the Scramble for Africa, (every major power swooped into Africa to snap up every colony they could). Impelling Islamic leaders, especially Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, and his followers to start the Banadir Resistance one of the longest anti-colonial struggles on the continent. They successfully repulsed British forces four times between 1890 and 1919, causing the British to retreat to the coastal regions.

In 1920, the Banadir Resistance collapsed after intensive British aerial bombardments, and Banadir territories were subsequently made protectorates, with Italy ruling southern Somalia, and the United Kingdom the far northern section. The two areas were known as Italian Somaliland and British Somaliland.

On August 3, 1940, Italian troops, including Somali colonial units, invaded British Somaliland, completing the conquest eleven days later. In January of 1941, a force of British troops launched a campaign to retake British Somaliland and liberate Italian Somaliland. By March 1941, the campaign was complete and the UK remained in control of Somalia until in end of the war.

Independence and dictatorship

During the Potsdam Conference, in November of 1945, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland, but only under close supervision and on the condition that Somalia would achieve independence within ten years. Neither the UK or Italy net the ten year goal, but on July 1, 1960, both Italian Somaliland and British Somaliland were given their independence and, after a referendum, united to form the country of Somalia. Their government was set up like most western countries,with a National Assembly and a President, a constitution was ratified through another referendum.

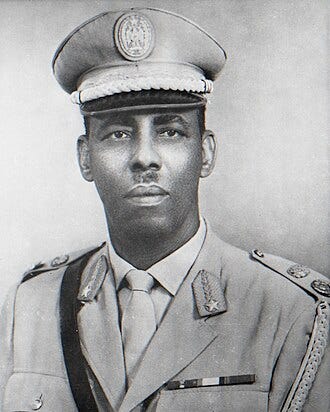

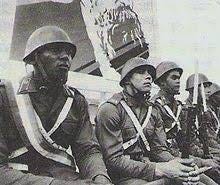

In 1967, Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, was elected president, however, on October 15, 1969 while the town of Las Anod, Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards, apparently over a clan grievance. Six days later, spurred into action by the assassination, the Somali Army seized power in a bloodless coup d’etat. The putsch was spearheaded by Commander of the Army Major General Mohamed Siad Barre.

The body that assumed power, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) was led by Barre, Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. The SRC renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic, (never a good thing), dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution. The new government established large-scale public works programs and successfully implemented an urban and rural literacy campaign. In addition to a nationalization program of industry and land, the new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab and African world. In 1974 Barre served as chairman of the Organization of African Unity and they joined the Arab League. In July of 1976, the SRC changed their name to the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP), a one-party government based on socialist and Islamic tenets, (that has always worked out so well).

In July 1977, after Barre's government sought to incorporate the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region of Ethiopia into a Greater Somalia, the Ogaden War broke out. By September 1977, Somalia controlled 90% of Ogaden, they had captured the strategic city of Jiiga and threatened to sever the train route from Dire Dawa to Djibouti. On February 1, 1978, a massive Soviet-sponsored intervention of 20,000 Cuban troops and several thousand Soviet “advisors”, came to the aid of the communist regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam. By March, the Somali troops were completely pushed out of Ogaden. The shift in support by the Soviet Union motivated the Barre government to seek a alliance with the United States, which had been courting the Somali government for some time. All in all, Somalia's initial friendship with the Soviet Union and later partnership with the United States enabled it to build the largest army in Africa.

In October 1980, the SRSP was disbanded, and the Supreme Revolutionary Council was re-established in its place. By this time, Barre's government had become increasingly unpopular. Many Somalis had become disillusioned with life under a socialist military dictatorship. Between 1987 and 1989 the Darod clan-dominated Barre regime perpetrated a genocide against members of the Isaaq Clan in northern Somalia. Estimates of the number of people killed range from 100,000 to 200,000. The Somali military even created a unit dubbed Dabar Goynta Isaaqa (The Isaaq Exterminators), who conducted a systematic pattern of attacks against unarmed, civilian villages, watering points and grazing areas of northern Somalia, killing many of the residents and forcing survivors to flee for safety to remote areas.

The regime was weakened further in the late 1980s as the Cold War drew to a close and Somalia's strategic importance was diminished. The government became increasingly totalitarian In an effort to hold on to power. Barre tried to quell the unrest by abandoning nationalism, and relying more and more on his own inner circle, while exploiting historical clan animosities. He ordered punitive measures against those he perceived as opposing him, especially in the north. The clampdown included the bombing of cities and the placing of over 20,000 mines in the north.

In response to these humanitarian abuses, Western donors cut aid to the Somali regime which, was heavily reliant on that aid. This resulted in a rapid and severe drop in value for the Somali Shilling and a retreat of the state, accompanied by mass military desertions.

Civil War

By the mid-1980s, resistance movements supported by Mengistu Haile Mariam in Ethiopia, had sprung up across the country. At a glance they were:

United Somali Congress (USC). The largest faction, and one of the first to take up arms against the Barre regime. They operated in southern Somalia especially in and around Mogadishu. They were comprised of members of the Hawiye clan. It was further divided into two factions, one lead by General Mohamed Farrah Aidid, made up of members of the Habar Gedir sub-clan, and the other led by Ali Mahdi Muhammad was comprised of members of the Abgal sub-clan.

Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM). Active mostly around Kismayo in southern Somalia and comprised of members of the Ogaden sub-clan of the Darood clan. It was also divided into two rival groups. One, led by Colonel Ahmed Omar Jess, was allied with General Aidid. The other faction, led by Colonel Aden Gabiyu, was allied with a third faction of the Ogaden sub-clan led by Mohamed Said Hirsi, Said Barre’s son-in-law, and known as General Morgan. Morgan’s group was allied with Ali Mahdi and therefore a rival of Colonel Jess.

Somali National Movement (SNM). This group was comprised of members of the Issaq Clan, under the leadership of Abdulrahman Ali Tur. This group declared an independent nation in the northwest of the country, called the Somaliland Republic.

Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF). Also operating in the north, it was comprised of members of the Majertain sub-clan of the Darood clan. They were opposed to the USC.

Somali National Front (SNF). Formed by Said Barre after his flight from Mogadishu but led by Omar Haji Mohamed, this faction was comprised of members of the Marehan sun-clan of the Darood clan, the majority of them were former members of the army. At the beginning of the civil war it was the strongest faction, because of the number of army troops in the group.

Southern Somali National Movement (SSNM). Centered in the town of Kismayo, this group was made up of members of the Biyemal sub-clan of the Dir clan. They opposed any faction of the USC, as well as the SPM.

Al-Itihaad al-Islamiya (AIAI). Founded by Hassan Dahir Aweys and Hassan Abdullah Hersi al-Turki as a non-violent Islamic movement but militarized after the fall of the Barre government. They drew members from across all clan lines but operated mostly in the north, fighting against the SSNM.

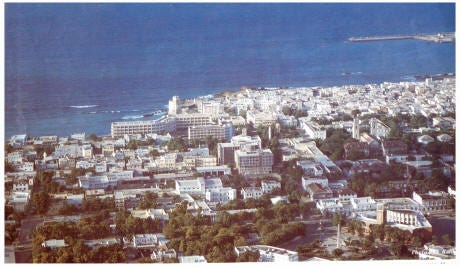

In 1990, as fighting in the north, between SNM rebels, the army and heavily armed pro-government militia intensified, USC rebels captured most of the towns and villages surrounding Mogadishu, (which led to some calling Barre “The Mayor of Mogadishu”). In December 1991, the USC entered Mogadishu and four weeks later, after the USC won battles against Barre's elite Red Berets, Barre’s hold on power in Somalia was finally broken.

In late December 1990, with the situation in Somalia, especially Mogadishu, deteriorating, violence quickly enveloped the city as rebels began clashing with government soldiers. On January 1, 1991, James Keough Bishop, the US Ambassador to Somalia, contacted the State Department requesting an evacuation of the embassy staff, it was approved the following day. On January 5, 1991, just ten days before the start of the coalition air campaign that kicked off the Gulf War, a company of Marines from the 1st Battalion 4th Marines, flew into, Mogadishu by helicopter, and evacuated 281 diplomats and other people from 30 different countries. All without firing a shot or taking any casualties. It would be nearly two years before any US personnel set foot inside the embassy compound again.

On January 26, 1991, with the situation in the country untenable, Said Barre, with his son-in-law General Morgan in tow, fled Mogadishu, in a tank filled with cash and gold worth $27 million, plundered from the Somali National Bank. He ran to Burdhubo, in southwestern Somalia, his clan stronghold. Twice, he attempted to retake Mogadishu, but in May 1991 was overwhelmed by General Mohamed Farrah Aidid's forced and sent into exile in Nigeria.

Even as the rebel groups were mopping up resistance and celebrating their victory, the various factions that had opposed Barre, now sought to achieve dominance in a new government. They began jostling for influence, authority and power in the vacuum left by Barre's departure. Ali Mahdi Mohamed of the USC was selected as the new president of Somalia, but the USC was an instrument of the Hawiye clan, and Ali Mahdi never received enough support from the rest of the country. The fighting, which now pitted the clans against one another, also led to the creation of new alliances and divisions. For instance, the USC itself split into two factions, the Somali Salvation Alliance led by Ali Mahdi and the Somali National Alliance led by General Aidid. No single group was strong enough to overcome the others in this unending fight for power and without a central government, anarchy, violence, and lawlessness reigned. In 1992, after four months of heavy fighting for control of Mogadishu, a ceasefire was agreed between Ali Mahdi and Aidid. Neither had seized control of the capital, and as a result, a “Green Line” was established between the east and west sides of the city, that divided their areas of control. I would become very familiar with that line during my time in Somalia.

Famine

The impetus for the US intervention in Somalia was a famine. Images of starving children were splashed across the nightly new for days. Those images, and the outcry they created, prompted the UN to act. In the summer of 1990, during the last year of Said Barre's regime, and before the full outbreak of the Somali Civil War, food shortages had begun. At the start of 1991, with the civil war in full swing, and following several years of decline, the formal economy collapsed. Simultaneously the country was hit with an exceptionally harsh drought. Farmers were unable to raise crops, and food itself became a weapon. To have it made your own group strong; to deprive it from your rivals weakened them as it strengthened you. The threat of losing food, or the ability to grow it, to armed militias was now added to the threat of being robbed by the everpresent gangs of bandits.

As agricultural production ceased, food prices skyrocketed across the south in mid-1991. In November later that year, major battles in Mogadishu and Kismayo closed the two main ports in Somalia. This led to the disappearance of food from many markets across southern Somalia. Warnings of famine began around December 1991, but were largely ignored by the United Nations and relief agencies. However, in March 1992, the Red Cross declared Somalia the "most urgent tragedy in the world" and warned that thousands of people would begin dying within weeks. With violence a reality of everyday life, everyone had to protect himself. Individuals armed themselves, formed local militias, or hired others for protection. Even private relief organizations became the targets of threats and extortion and had to resort to the hiring of armed bodyguards. It truly became a case of "every man against every man."

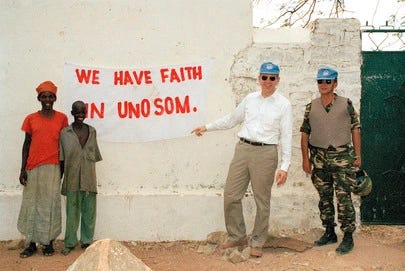

UNOSOM I

The UN had been engaged in Somalia from early in 1991 when the civil strife began, but UN personnel were withdrawn on several occasions during periods of protracted violence. After diplomatic interventions by the Organization of African Unity, the League of Arab States and the Organization of the Islamic Conference, as well as a series of Security Council resolutions (733 and 746), a ceasefire between the SNA and the SSA was reached. By the end of April 1992, the Security Council adopted Resolution 751 which provided for the establishment of a security force of 50 UN troops in Somalia to monitor the ceasefire, known as the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM), it existed only with the consent of the SNA and SSA. The resolution also allowed for an expansion of the security force, with 500 troops initially discussed. The first group of ceasefire observers arrived in Mogadishu in early July 1992. Despite the UN's efforts, the ceasefire was ignored. The fighting continued and even increased, putting the relief operations at risk. Aidid and Mahdi proved to be difficult negotiating partners and continually frustrated attempts by the peacekeepers to monitor the ceasefire. In August 1992 the Security Council agreed to send another 3,000 troops to the region to protect relief efforts, however, most of these troops were never sent.

Over the final quarter of 1992, the situation in Somalia continued to get worse. Factions in Somalia were splintering into smaller factions and splintering again. Agreements for food distribution with one party were worthless when the supplies had to be shipped through the territory of another and some elements were actively opposing the UNOSOM intervention. Troops were shot at, aid ships attacked and prevented from docking, cargo aircraft were fired upon and aid agencies, public and private, were subject to threats, robbery and extortion. Meanwhile, hundreds, if not thousands of people were starving to death every day. By November 1992, General Mohamed Farrah Aidid had grown confident enough to formally defy the Security Council and demand the withdrawal of peacekeepers, as well as declaring hostile intent against any further UN deployments.

UNITAF

In November 1992, the United States offered to establish a multinational force under its own leadership to secure the country for the humanitarian operation. This offer was accepted by the Security Council, and what became known as the Unified Task Force (UNITAF) was authorized to use "all necessary means" to ensure the protection of the relief efforts.

On the evening of December 4, 1992, President George H. W. Bush addressed the nation, leaning into his post-Cold War policy of a kinder, gentler America, he announced that US troops would be sent to Somalia to ensure food deliveries reached the correct people and the suffering of the Somali people would end. The US contingent would be operating under the name Operation Restore Hope, and would be joined by a multinational force, collectively known as the United Task Force. President Bush stated that the UNITAF mission would be a transitional action under US control, and would be divided into four phases.

Troops would secure key harbor and airport sites in Mogadishu and Baledogle.

The security zone would be extended to encompass the surrounding regions of southern Somalia.

The security zone would be extended further, reaching Kismayo and Bardera, and securing routes for humanitarian operations.

The US would transfer operations to the United Nations and withdraw most of our troops.

UNITAF was composed of forces from 27 different countries; Australia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Botswana, Canada, Egypt, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Greece, India, Ireland, Italy, Kuwait, Morocco, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the United Kingdom and Zimbabwe. However, the vast majority of troops (25,000 out of 37,000), were sent by the United States. The important task of organizing who went where, to do what, became a negotiation between the supplying governments and the Joint Task Force (JTF) staff. The relations between the different units involved in the effort and the JTF would be an ongoing issue for the entire duration of UNITAF and many accommodations would be made in order to facilitate a smooth operation. One example was that all non-English speaking units were given and liaison team consisting of a US service member that spoke their language and a communicator, in order to make coordination easier and allow the unit to get anything it needed from the US without a big hassle. More on that in Part II.

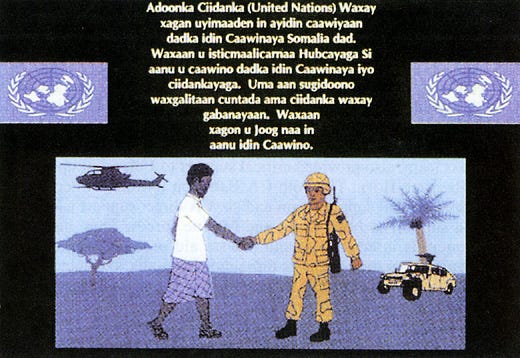

Operation Restore Hope began on December 6, 1992, when Navy SEALs began three days of hydrographic surveys and reconnaissance of the potential landing beach, the airport and port area. On December 8, the US conducted leaflet drops over Mogadishu, warning the population of the imminent arrival of US and UN troops

At 5:40 AM, on December 9, the Marines of 2nd Battalion 9th Marines, (2/9), and SEALs landed on a beach near the airport. They came out of the dark surf and were greeted by the bright lights of television cameras from many different TV networks. If there was an investigation into the leaking of the landing beach to the press, I’m not aware of any conclusion. Before noon, the port and the airport are secured and military airplanes start landing, bringing in a company of the 2nd French Foreign Legion Parachute Regiment. The next day 1st Battalion 7th Marines and 3rd Battalion 11th Marines arrived.

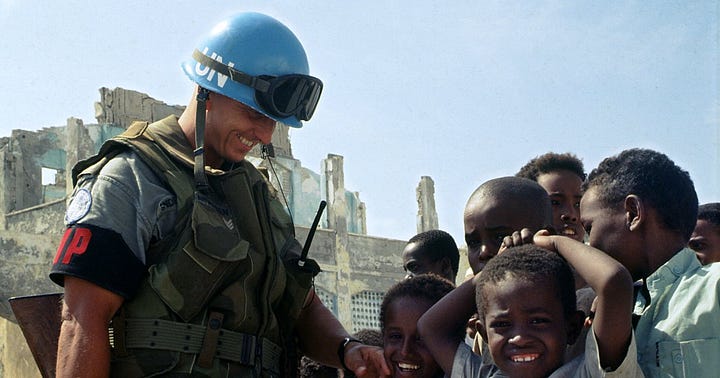

As the coalition forces moved into Mogadishu they encountered a city that had felt the ravages of two years of civil war and anarchy. The sound of gunfire could be heard throughout the city. There was no electricity, running water, or sanitation system. There was no functioning judicial system and law enforcement was nonexistent. Public buildings had been looted and destroyed and most private homes were severely damaged; virtually every structure was missing its roof and had broken walls, doors, and windows. The commerce of the city was at a standstill. Schools were closed and gangs of youths roamed the streets. Crowded refugee camps seemingly filled every parcel of open land, and new graves were encountered everywhere.

India Company 2/9 and 1/7 secured the airport in Baidoa and Bardera, while Golf Company 2/9 and elements of the Belgian 1st Parachute Battalion conducted an amphibious landing at the port city of Kismayo. As UNITAF forces pushed deeper into the interior of the country, they made the areas safe for food distribution.

Because the mandate of UNITAF was to protect the delivery of food and other humanitarian aid, the operation was regarded as a success. UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali determined that the presence of UNITAF troops had a "positive impact on the security situation in Somalia and on the effective delivery of humanitarian assistance.” An later epidemiological survey determined that approximately 10,000 lives had been saved by the military intervention. The transition to UNOSOM II was where things took an unfortunate turn for the US and the UN.

UNOSOM II

The United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) was the second phase of the United Nations intervention in Somalia taking place from March 1993 until March 1995. UNOSOM II was different than either UNOSOM I or UNITAF because of the focus on a nation-building mission. According to the UN Security Council resolution authorizing the mission (814), the operation's objectives were to aid in relief provision and economic rehabilitation, foster political reconciliation, and re-establish political and civil administrations across Somalia.

In June 1993, UNOSOM II was transformed into a military campaign as it found itself entangled in an armed conflict against General Aidid and the SNA. As the focus turned more and more towards the conflict with the SNA, the task of political reconciliation, and humanitarian aid took on a peripheral role. Three months into the conflict with the SNA, the US would launch Operation Gothic Serpent to finally capture or kill General Aidid. The Battle of Mogadishu would mark the end of significant US military operations in Somalia, and US forces would leave the country by the end of 1994.

In this first post I have outlined the history of Somalia, the initial UN intervention, the US-led UNITAF period, the transfer to UNOSOM II and the change in the mission that led to the humiliation of the Battle of Mogadishu. Next time I will relate my personal experiences in Somalia and how the common Marine could see what was happening, even if the brass at UNITAF and in Washington DC could not. I hope your are enjoying my posts as much as I enjoy writing them. Please pass this on to everyone who might be interested.

Chris