What's Wrong with the Government? Part IV

The Supreme Court and their role in our journey to an administrative state

In Part III of my series

I examined the role of three presidents in the rise of the administrative state and our journey farther and farther away from the republic envisioned by the Founders. Today I will look at the role the Supreme Court has played or maybe more accurately, has refused to play in the unchecked growth of a government that is increasingly unanswerable to the American people.

The Supreme Court:

As I wrote in Part I,

the role of the Supreme Court was originally somewhat vague but the Supreme Court is supposed to have original jurisdiction over all cases that arise between the states, between a state and people of another state, between people of the same state if the issue is regarding the land of another state or territory and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make. It was never explicitly mentioned if the Supreme Court was able to rule if a law properly passed by the Legislature was constitutional or not, but the one of the first cases heard by the court Marbury v Madison settled that issue. I will now look at some of the landmark cases that either tried to keep the country on the right path or sent us down this road we are currently on.

Marbury v. Madison

In the fiercely contested presidential election of 1800 Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican (sounds like a horrible combination to me), easily won the popular vote over incumbent president and Federalist, John Adams but just narrowly won in the Electoral College. Once it became clear Adams was going to lose, he did everything he could to fill federal offices with "anti-Jeffersonians". On March 2, 1801, just two days before his presidential term ended, Adams nominated nearly 60 Federalist supporters to new circuit judge and justice of the peace positions the Federalist-controlled Congress had recently created. These last-minute nominees, whom Jefferson's supporters derisively called the “Midnight Judges”, included William Marbury, a prosperous Maryland businessman, ardent Federalist, and vigorous supporter of Adams.

On March 3 1801, after their appointments were approved by the Senate en mass and signed by Adams, Secretary of State John Marshall sent the commissions to be delivered. Nearly all reached their addressees, however some, including Marbury’s did not. On March 4, 1801, when Jefferson was sworn in, he instructed his Secretary of State, James Madison, to withhold the undelivered commissions. In Jefferson's opinion, the commissions were void because they had not been delivered before Adams left office. Without the commission certificates, the appointees were unable to assume their new offices and duties. Over the next several months, Madison steadfastly refused to deliver Marbury's commission to him. Finally, in December 1801, Marbury filed a lawsuit against Madison in the Supreme Court, asking the Court to force Madison to deliver his commission.

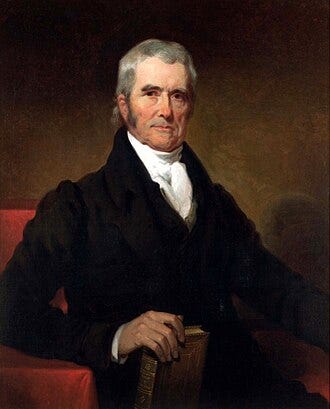

On February 24, 1803, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous 4–0 decision against Marbury. The opinion written by Chief Justice John Marshall (yes, the same guy who was just Secretary of State), tailored the opinion around a series of three questions:

Did Marbury have a right to his commission?

If Marbury had a right to his commission, was there a legal remedy for him to obtain it?

If there was such a remedy, could the Supreme Court legally issue it?

The court held that Marbury did have a right to the commission and that a Writ of Mandamus, a type of court order that commands government officials to perform an act their official duties legally require them to perform, was the proper remedy for Marbury's situation. However, this raised the issue of whether the Court, which was part of the judicial branch, had the power to command Madison, who as secretary of state was part of the executive branch. This brought the case down to the final question, did the Supreme Court have jurisdiction to allow it to issue the writ? The answer depended entirely on how the Court interpreted the Judiciary Act of 1789. The Court interpreted the Judiciary Act to have given it original jurisdiction over lawsuits for writs of mandamus. This meant that the Judiciary Act had taken the Constitution's initial scope for the Supreme Court's original jurisdiction, which did not cover cases involving writs of mandamus, and expanded it to include them. The Court ruled that Congress cannot increase the Supreme Court's original jurisdiction as it was set down in the Constitution, and it therefore held that the relevant portion of Section 13 of the Judiciary Act violated Article III of the Constitution. After ruling that Section 13 of the Judiciary Act conflicted with the Constitution, the Court struck down the section, in the Court's first ever declaration of the power of judicial review, setting the role of the court for the years to come.

Little v. Barreme

During the Quasi War (an undeclared naval war with France from 1798 to 1800) Congress passed a law authorizing the navy to seize "vessels or cargoes that are apparently, as well as really, American" and "bound or sailing to any French port" in an attempt to prevent American vessels transporting goods to France. In addition to this law, President John Adams signed an executive order "to intercept any suspected American ship sailing to or from a French port” and authorized Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert to carry it out. The frigate USS Boston, captured the Danish brig Flying-Fish which had left the French-controlled Haitian port of Jeremie. She was suspected of being an American ship in violation of the embargo on France. A federal district court judge freed the Flying-Fish, since it was neither an American vessel nor going to a French port, but did not award damages for its illegal capture. The owners of the Flying Fish appealed and the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled that George Little, the captain of the Boston should pay damages. Captain Little appealed to the Supreme Court on the grounds that he was only following a presidential order and therefore should not be held responsible for any damages for his mistake. In a unanimous decision, written by Chief Justice John Marshall, the Court affirmed the Court of Appeals decision stating the President did not have "any special authority" to order the seizure of non-American ships and ships departing French ports. Even if the Flying-Fish had been an American ship, it still would not have been subject to seizure. Therefore, since Little had illegally seized the ship, he was also liable for damages. Marshall wrote "Is the officer who obeys [the President's order] liable for damages sustained by this misconstruction of the act, or will his orders excuse him? The instructions cannot change the nature of the transaction, or legalize an act which without those instructions would have been a plain trespass." Marshall also wrote that:

It is by no means clear that the President of the United States, whose high duty it is to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed," and who is commander in chief of the armies and navies of the United States, might not, without any special authority for that purpose, in the then existing state of things, have empowered the officers commanding the armed vessels of the United States to seize.

This ruling should be the precedent used for every substantive executive order issued by a president.

The Aurora v. United States

In 1809 Congress passed a law that stated the president will determine if England and France are seizing American merchant vessels and impressing American sailors. The law stated that if the president makes that determination, than an embargo of all cargo imported or exported from those countries would take effect. In 1810 President Madison made the determination that England was still taking American vessels and crew. This finding on November 2, 1810, automatically led to the embargo against English goods. The announcement of the embargo reached England by December 13. The Aurora left Liverpool on December 16 and when she docked in New Orleans on February 2, 1811, her cargo was impounded. The owner, Robert Burnside, sued the government, stating that the Congress did not have the authority to delegate the lawmaking power to the president. The court ruled unanimously in an opinion written by Associate Justice William Johnson, that in this case the President was merely acting as an agent of Congress and not making law. The law was clear in that it only directed the president to make a finding of fact, and it was that fact which would trigger the law coming into force or not. Therefore, the Executive branch was not making a law. This is an important decision because it set a precedent for the actions of congress and the president. We will see in a future case that the precedent was short-lived.

McCulloch v. Maryland

In 1818, the state of Maryland passed legislation to impose taxes on the Second Bank of the United States. James W. McCulloch, the cashier of the Baltimore branch of the bank, refused to pay the tax. The state appeals court held that the Second Bank was unconstitutional because the Constitution did not provide a textual commitment for the federal government to charter a bank. In 1819 in a unanimous decision, written by or old friend, Chief Justice John Marshall, the Court held that Congress had the power to incorporate the bank and that Maryland could not tax instruments of the national government employed in the execution of constitutional powers. According to Marshall, the “necessary and proper” clause (Art. I, Section 8), implied that Congress possessed powers not explicitly outlined in the Constitution. Marshall redefined “necessary” to mean “appropriate and legitimate,” covering all methods for furthering the objectives of the enumerated powers. Marshall also held that while the states retained the power of taxation, the Constitution and the laws made in addition to it, are supreme and cannot be controlled by the states. Marshall maintained that since the legislature has the authority to tax and spend, it therefore has authority to establish a national bank, as being "necessary and proper" to that end. This decision started the US down the road to the administrative state because now nearly anything could be seen to be “necessary and proper”.

Wayman v. Southard

This case was another “necessary and proper” case, as well as one that allowed Congress to delegate their powers. The 1825 case involved the Process Act of 1792, which was one of several federal statutes that authorized the federal courts to establish their rules of operation, provided such rules were not against the laws of the United States. The Kentucky state legislature attempted to set the procedures for trials involving writs of execution (directing a law enforcement officer to seize the property of the defendant to obtain the funds necessary to pay a judgment), in federal courts in line with those in Kentucky state courts. In a unanimous decision, written by Chief Justice John Marshall, the court ruled that the “necessary and proper” clause allowed the courts to set their own rules of operation. He made a distinction between the essential legislative functions of Congress, which it should regulate itself, and the subordinate rules and procedures which he felt could be more efficiently established by other entities. He also wrote that state legislatures were incapable of receiving delegated power from Congress, that left the federal courts themselves as the only logical choice. Wayman v. Southard was one of the first cases to explore delegation of congressional power and Marshall's opinion solidified the right of Congress to delegate power to other federal entities.

Bank of the United States v. Halstead

In another 1825 case the Bank of the United States, which had been chartered by Congress in 1791, sued Peter Halstead, a North Carolina resident, for defaulting on a loan. Halstead argued that the bank's charter was unconstitutional and therefore the bank had no legal standing to enforce the debt. The court's ruling in this case addressed the constitutional authority of Congress to create the Bank of the United States. Chief Justice John Marshall, (him again?), who wrote the opinion of the court, held that the creation of the bank was indeed within the powers granted to Congress in the Constitution. The decision in Bank of the United States v. Halstead affirmed the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States and added to the precedent of the interpretation of the “necessary and proper” clause. Overall, the case of Bank of the United States v. Halstead played a significant role in shaping the understanding of the constitutional powers of Congress and the economic structure of the United States.

Field v. Clarke

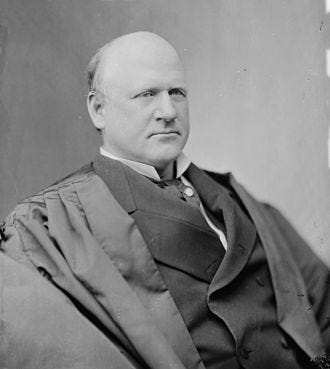

In 1890 Congress passes the appropriately named Tariff of 1890. This law directed President Benjamin Harrison to impose tariffs on specific goods from specific countries whose tariff policy was determined by the president to be unequal and unreasonable. Several import businesses, including Marshall Field & Co., argued that the tariff represented an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the President. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the Tariff Act of 1890 was indeed constitutional. In an opinion written by Associate Justice John Harlan I, the unanimous court ruled that this was not a instance of Congress delegating it’s legislative duty to another entity but that the President was given the power of discretion rather than the power of legislation. All he was being asked to do was to determine if a country’s tariff was unequal and unreasonable. If that was the case, the law would do the rest. Another Associate Justice, the very Greek named, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, concurred with the opinion but stated that Harlan should have used Aurora v United States as the precedent. I think they are both wrong, the Aurora case was clearly a simple yes or no factual question but the Field case (Marshall Field himself was the plaintiff) is not a simple yes or no question, it is a matter of opinion, which is squarely in the realm of the Legislative branch and therefore, is an unconstitutional delegation of power.

Schenck v. United States

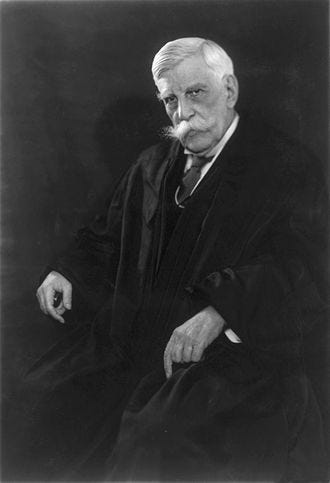

During World War I, socialists Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer distributed leaflets declaring that the draft violated the Thirteenth Amendment prohibition against involuntary servitude. The leaflets urged the public to disobey the draft, but advised only peaceful action. Schenck was charged with conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act of 1917, attempting to cause insubordination in the military and obstruct recruitment. After they were convicted, Schenck and Baer appealed on the grounds that the statute violated the First Amendment. The Court held that the Espionage Act did not violate the First Amendment and was an appropriate exercise of Congress’ wartime authority. Writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, concluded that courts owed greater deference to the government during wartime, even when constitutional rights were at stake. He wrote that the First Amendment did not protect Schenck from prosecution, even though,

"in many places and in ordinary times, Schenck, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within his constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. In this case the words used, are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent."

Holmes reasoned that the widespread dissemination of the leaflets was sufficiently likely to disrupt the conscription process. He also famously, compared the leaflets to falsely shouting “Fire!” in a crowded theater. A quote that is often taken out of context and used to condemn all speech that is controversial. He said:

The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.

This was a landmark ruling on free speech and in subsequent cases, when it appeared to him that the Court was departing from the established precedents in similar cases, Holmes dissented, reiterating his view that expressions of honest opinion were entitled to near absolute protection, but that expressions made with the specific intent to cause a criminal harm, or that threatened a clear and present danger of such harm, could be punished. In Abrams v. United States, he elaborated on the common-law privileges for freedom of speech and of the press, and stated his conviction that freedom of opinion was central to the constitutional scheme because competition in the "marketplace" of ideas was the best test of their truth. Holmes’ position was a real dichotomy because on one hand he believed in the absolute right of free speech and at the same time thought that some speech was dangerous and should be banned.

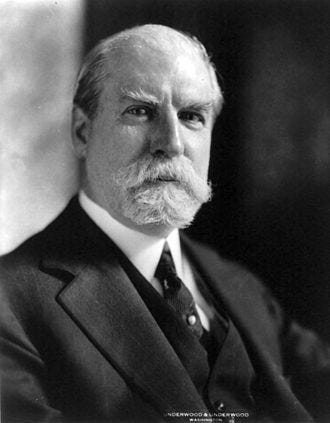

J.W. Hampton v. United States

J.W. Hampton Jr. & Company imported barium dioxide into New York and was assessed an import duty of six cents per pound, two cents more than the rate originally specified by law. The collector of customs had raised the rate pursuant to a presidential proclamation issued under the Tariff Act of 1922. The act authorized the president to adjust the duties imposed by the act and provided criteria for determining adjustments. J.W. Hampton Jr. & Company brought a claim in United States Customs Court, they believed that the president's exercise of a power reserved for Congress, the authority to adjust tariff rates to protect American business, was unconstitutional. The firm also contended that Congress may only impose taxes for the purpose of generating revenue and argued that the Tariff Act was unconstitutional because Congress had imposed the act's import duties in order to protect American industries.

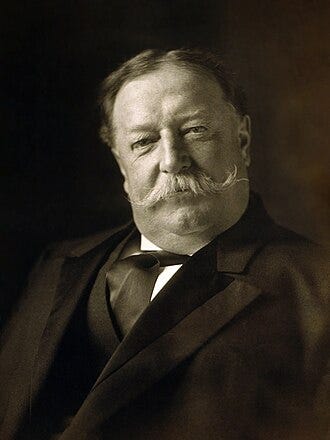

The customs court held that the act was constitutional as did the Court of Customs Appeals and the case went to the Supreme Court. On April 9, 1928 Chief Justice William Howard Taft (yes, the former president), writing the decision for a unanimous court, stated that that the Tariff Act of 1922 did not contain an unconstitutional delegation of legislative authority because Congress provided the president with instructions on when and how to adjust the tariff rates established by the law. Taft also rejected the reasoning, arguing that a tax could not be enacted to protect American business. He said that Congress could have additional motives for implementing a tax and as long as the tax also had the purpose and effect of raising revenue it was constitutional. However the most important part of Taft’s opinion was the section of his opinion where he sets a new precedent for declaring the act constitutional. He writes:

If Congress shall lay down by legislative act an intelligible principle to which the person or body authorized to fix such rates is directed to conform, such legislative action is not a forbidden delegation of legislative power.

The “intelligible principle” precedent became the standard as a legal test for whether or not a delegation of authority by Congress to the executive branch violates the separation of powers principle as well as the nondelegation doctrine. It will be used in many other cases throughout the intervening years to rule a whole host of laws as constitutional.

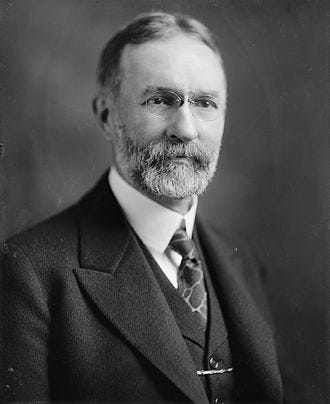

Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) aimed to alter the government's approach to regulating business. The NIRA authorized the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to create industry-wide "codes of fair competition," with input from both businesses and labor unions, to replace existing antitrust laws. The NRA formulated the "Code of Fair Competition for the Live Poultry Industry of the Metropolitan Area in and about the City of New York" (the Live Poultry Code), which set rules for the poultry industry regarding hours, wages, health and safety, and other practices. Schechter Poultry Corporation was charged and convicted of 19 code violations and the ruling of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit was also against them. Schechter petitioned the Supreme Court, arguing that NIRA violated the nondelegation doctrine, by unlawfully delegating legislative authority to the National Recovery Administration. Schechter also claimed that the Live Poultry Code was unconstitutional in violation of the Tenth Amendment, because the federal government had no authority to regulate intrastate commerce and violated the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment. In an opinion authored by Chief Justice Charles Hughes, the unanimous Court held that the Act was "without precedent" and was an unconstitutional delegation of legislative authority.

The President cannot be allowed to have unbridled control to make whatever laws he believes to be necessary to achieve a certain goal. The law did not establish rules or standards to evaluate industrial activity, meaning Congress failed to provide the necessary guidelines for the implementation of this functionally legislative process. The court also held that Section 3 of NIRA violated the Tenth Amendment, though it declined to rule on the Fifth Amendment question. The Schechter ruling was part of a series of judicial setbacks to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal agenda that may have inspired his attempt to pass the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. The bill would have empowered the president to appoint a new Supreme Court justice for every existing one over the age of 70, which would have given Roosevelt six new appointments upon its passing. This led to the abrupt reversal of the Court, sometimes called ”The Switch in Time that Saved Nine”. Since this change, the court has never declared any New Deal legislation unconstitutional.

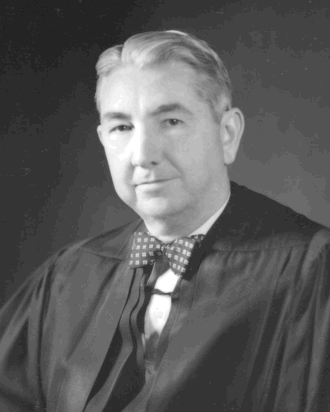

Humphrey's Executor v. United States

The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 created the Federal Trade Commission with a mandate to "prevent unfair methods of competition in commerce." The commission consisted of five members to be appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, with not more than three of the members being of the same political party. Members were to serve terms of seven years and "Any commissioner may be removed by the President for inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” On December 10, 1931, William E. Humphrey was appointed to serve a seven year term on the Federal Trade Commission by President Herbert Hoover. However, because he was a Hoover appointee and opposed most of the New Deal programs President Franklin Roosevelt wished to enact, on July 25, 1933, Roosevelt asked for Humphrey's resignation. On October 7, 1933 when Humphrey still had not resigned, Roosevelt had him removed from office. Humphrey rejected this action and attempted to continue performing his duties until his death on February 14, 1934. Humphrey's estate then sued to recover the salary due to him for the time after his removal.

On May 27, 1935 Associate Justice George Sutherland wrote the opinion for a unanimous court. The Court distinguished between executive officers and quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial officers. The Court held that the latter may be removed only with procedures consistent with statutory conditions enacted by Congress, but the former serve at the pleasure of the President and may be removed at his discretion. The Court ruled that the Federal Trade Commission was a quasi-legislative body because it adjudicated cases and promulgated rules. Therefore, the President could not fire a member solely for political reasons and Humphrey's firing was improper. The government was ordered to pay the estate of Humphrey $50,000, the pay Humphrey was owed for the time from his firing to the end of his term. Justice Sutherland argued that Congress may create officials who may not be fired by the president because their duties are quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial rather than executive in nature and this argument has served as the foundation for the modern regulatory state.

United States ex rel. Accardi v. Shaughnessy

Joseph Accardi was an Italian national who entered the United States illegally in 1932. Deportation proceedings were brought against him in 1947. Accardi sought a discretionary suspension of deportation by the Attorney General. After the hearing examiner and the Acting Commissioner of Immigration denied the requested relief, but before the case reached the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), the last stop before a further discretionary appeal to the Attorney General, the Attorney General announced at a press conference that he planned to deport a confidential list of "unsavory characters. Accardi's name happened to be on the list, which was distributed to members of the BIA, which then affirmed the denial of suspension of deportation. The Supreme Court reversed the denial of habeas relief by the lower courts with the majority ruling that the Attorney General had violated the principle that agencies must follow their own regulations.

Speaking for the Court, Associate Justice Thomas Clark reasoned that the Attorney General's internal distribution of the list of unsavory characters violated regulations fixing the procedures for processing petitions for suspension of deportation. In particular, the regulations, by directing the BIA to "exercise such discretion and power conferred upon the Attorney General by law," meant that the BIA was to exercise its authority according to its own "understanding and conscience," and that the Attorney General had "denied himself the right to sidestep the Board or dictate its decision in any manner. In other words, the regulations implicitly established the BIA as an impartial adjudicator, and the Attorney General's edict interfered with the Board's impartiality. The Court said that Accardi was entitled to a new hearing before the Board, untainted by any preannounced view from the Attorney General. Accardi might again be denied suspension of deportation upon rehearing, "but at least he will have been afforded that due process required by the regulations in such proceedings. The "Accardi" decision requires that government officials follow agency regulations. The Accardi doctrine has since become a foundation for the rule that requires governmental agencies to observe their own rules, even when it is not expedient. Unpublished agency guidelines are not viewed as binding rules under the Accardi doctrine because guidelines do not have the force and effect of law. Agency guidelines establish uniform governmental policies and purport to establish self-imposed constraints on agency actions. Some guidelines, however, not only set internal policy, but also establish procedural and substantive restraints that protect persons from arbitrary treatment by government officials.

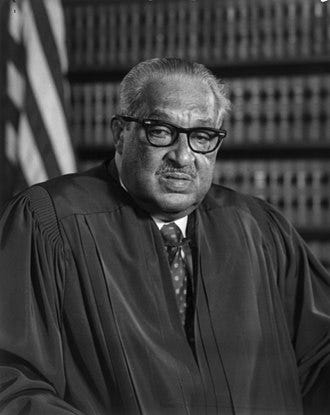

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe

The federal government, with the approval of the Memphis City Council, proposed a plan to build a six-lane interstate highway through Overton Park, which would have resulted in the destruction of 26 acres of the park. The route had been approved by the Bureau of Public Roads in 1956 and the Federal Highway Administrator (the BPR's successor) in 1966. The passage of the Department of Transportation Act of 1966, however, created the Department of Transportation—a new department that absorbed several previous entities and assumed their responsibilities. The act also included new requirements for projects involving public parks, which had previously been popular targets for highway development because the lack of inhabitants and major structures made them easier to acquire. Section 4(f) of the act put forth the following requirements:

After the effective date of this Act, the Secretary shall not approve any program or project which requires the use of any land from a public park, recreation area, wildlife and waterfowl refuge, or historic site unless (1) there is no feasible and prudent alternative to the use of such land, and (2) such program includes all possible planning to minimize harm to such park, recreational area, wildlife and waterfowl refuge, or historic site resulting from such use.

the secretary of transportation was required to conduct a review of any project involving parks to ensure that those conditions were not violated. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1968 updated Section 4(f) by adding the following language:

It is hereby declared to be the national policy that special effort should be made to preserve the natural beauty of the countryside and public park and recreation lands, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and historic sites.

A local group calling itself Citizens to Preserve Overton Park sued Secretary of Transportation John Volpe to challenge the plan. Both the United States District Court for the Western District of Tennessee and the United States Court of Appeals of the 6th Circuit ruled in favor of Volpe. The group appealed to the Supreme Court and on March 2, 1971, the Court ruled in favor of Citizens to Preserve Overton Park in a 6-2 (with one Justice absent) decision. Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote the opinion and he wrote that although Volpe had not been required to provide formal findings from his review, the district court had not used all available records when conducting judicial review of Volpe's actions. Therefore, the district court had approved Secretary Volpe's review using insufficient evidence. Marshall wrote, "We agree that formal findings were not required. But we do not believe that in this case judicial review based solely on litigation affidavits was adequate.” The case was remanded to the district court to conduct another review based on all of the available documentation. Overton Park is one of the most important cases in the administrative law realm, marking a shift in how lawyers attacked federal regulation. The rulings conclusion that courts must examine the entire record of an agency's decision established the "hard look" doctrine. It also stands as a notable example of the power of litigation by grassroots citizen movements to block government action.

Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc

This might be the most important case on this list after Marbury v Madison. It has had a huge effect on the rise of the administrative state and the inability of the courts to do anything about it. It has literally been sited thousands of time in court cases around the country. This case established the principle known as Chevron deference.

The decision involved a lawsuit challenging the government's interpretation of the word "source" in an environmental statute. In 1977, Congress passed a bill amending the Clean Air Act of 1963. The bill changed the law so that any company that planned to build or install any major source of air pollutants were required to go through an elaborate "new-source review" process before they could proceed. The bill did not precisely define what constituted a "source" of air pollutants, and so the EPA formulated a definition as part of implementing the changes to the law. The EPA's initial definition of a "source" of air pollutants covered essentially any significant change or addition to a plant or factory, but in 1981 it changed its definition to be simply a plant or factory in its entirety. This allowed companies to avoid the "new-source review" process entirely if, when increasing their plant's emissions through building or modifying, they simultaneously modified other parts of their plant to reduce emissions so that the overall change in the plant's emissions was zero. The Natural Resources Defense Council, an American non-profit environmental advocacy organization, filed a lawsuit challenging the legality of the EPA's new definition.

The United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit set aside the agency's regulation as inappropriate for a program enacted to improve air quality. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court and in a unanimous decision written by Associate Justice John Paul Stevens, the court reversed the circuit court’s decision.

Justice Stevens began his opinion by clarifying the scope and extent to which a federal court should defer to a federal agency's interpretation of a statute, which the agency itself has the authority and obligation to administer, he wrote:

When a court reviews an agency's construction of the statute which it administers, it is confronted with two questions. First, always, is the question whether Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue. If the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of the matter; for the court, as well as the agency, must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress. If, however, the court determines Congress has not directly addressed the precise question at issue, the court does not simply impose its own construction on the statute, as would be necessary in the absence of an administrative interpretation. Rather, if the statute is silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue, the question for the court is whether the agency's answer is based on a permissible construction of the statute. If Congress has explicitly left a gap for the agency to fill, there is an express delegation of authority to the agency to elucidate a specific provision of the statute by regulation. Such legislative regulations are given controlling weight unless they are arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to the statute. Sometimes the legislative delegation to an agency on a particular question is implicit rather than explicit. In such a case, a court may not substitute its own construction of a statutory provision for a reasonable interpretation made by the administrator of an agency. Judges are not experts in the field, and are not part of either political branch of the Government. Courts must, in some cases, reconcile competing political interests, but not on the basis of the judges' personal policy preferences. In contrast, an agency to which Congress has delegated policymaking responsibilities may, within the limits of that delegation, properly rely upon the incumbent administration's views of wise policy to inform its judgments. While agencies are not directly accountable to the people, the Chief Executive is, and it is entirely appropriate for this political branch of the Government to make such policy choices - resolving the competing interests which Congress itself either inadvertently did not resolve, or intentionally left to be resolved by the agency charged with the administration of the statute in light of everyday realities. When a challenge to an agency construction of a statutory provision, fairly conceptualized, really centers on the wisdom of the agency's policy, rather than whether it is a reasonable choice within a gap left open by Congress, the challenge must fail. In such a case, federal judges - who have no constituency - have a duty to respect legitimate policy choices made by those who do. The responsibilities for assessing the wisdom of such policy choices and resolving the struggle between competing views of the public interest are not judicial ones.

The Chevron deference defines the extent to which a federal court, in reviewing a federal government agency's action, should defer to the agency’s construction of a statute. When such a gap is implicitly left by Congress, the court is not to substitute its own construction of the statute as long as the agency’s interpretation is reasonable. In practice, Chevron deference enables agencies to often overstep their authority by treating vague language or doubtful gaps in a statute as authorization for actions that the agencies favor but which Congress never intended. In other words, they’re the “experts” and they will tell us what the law means.

Our only hope in ever trying to roll back the size and reach of government is three cases on the Supreme Court docket.

Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo

In Loper Bright, the National Marine Fisheries Service found a gap in the Magnuson-Stevens Act and “discovered” a previously unknown power to require small fishing vessels to pay for their federally mandated at-sea monitors who enforce restrictions on methods and amounts of fishing. The fishermen argue that Chevron deference lets agencies steal the courts’ power to say what the law is and Congress’ power to write laws, leaving citizens subject to regulators’ whims. Therefore, they contend that the court should overrule Chevron or drastically constrain its application.

Securities and Exchange Commission v. Jarkesy

Loper Bright will have major implications for citizens fighting administrative agencies in courts, but it won’t have much of an effect if citizens can’t get their cases into courts. Agencies prosecute many of their cases before tribunals within the agencies themselves. There, agency employees called administrative law judges decide those cases in the first instance, and other judge employees hear appeals. Jarkesy may limit the use of these in-house tribunals. The Securities and Exchange Commission suspected that George Jarkesy Jr. and his investment advisor committed fraud, and it brought an enforcement action against them before one of its judges. The defendants argued that the in-house tribunal violates their Seventh Amendment right to have a jury trial. That right applies to “suits at common law”, of which fraud is one. So, the defendants argue, the Constitution forbids the SEC from bringing their case to its in-house tribunal. They also argued that Congress gave the agency too much discretion to choose whether to bring cases to courts or to administrative law judges. If the defendants win their Seventh Amendment claim, agencies will have to send more of their enforcement cases to federal court. A win for the defendants would partially dispel the specter of bias that haunts administrative law judges, who rule in their employers’ favor 90% of the time.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Community Financial Services Association of America

While agencies often try to make themselves self-contained governments, sometimes Congress lends them a hand. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is the most dramatic example. When Congress created the bureau in 2010, it did everything it could to make sure that the CFPB answered to no one but itself. Relevant to this lawsuit, Congress created an unusual funding mechanism for the CFPB. Whereas most agencies receive their money from congressional appropriations, the CFPB gets to take as much money as it wants (subject to a loose cap) directly from the Federal Reserve. This makes the CFPB uniquely immune from congressional control, and like the SEC, the CFPB has rulemaking and law enforcement powers. These can easily be used to advance the CFPB’s own agenda rather than that of Congress.

Of course the real way to start to dismantle the leviathan that has become our government is to get strong candidates with a desire to turn this out of control roller coaster were on, around. If we can get enough people in Congress that are passionate about our traditional form of government and don’t get sucked into the “inside the beltway” mentality, we might be able to make a difference. I hope you have enjoy this series of posts and please feel free to share them with anyone who might be interested. Until next time, you stay classy Substack.

Chris