What's Wrong with the Government? Part III

The third part of a four part ground-breaking examination of the US government.

Part II looked at the Progressives and the role of the legislature in the current mess. Today I will look at the Executive Branch and the three main Presidents involved in the expansion of the role of government, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt.

Executive Branch:

At the same time the administrative state was being built by the legislature, measures were underway to ensure that these new bureaucracies would be “professional.” According to the theory of the Progressives, bureaucracies would have to be staffed by people who were nonpartisan and not susceptible to the pressures of public opinion. Their work would be scientific, not political, and this meant that elected officials should not be able to appoint or remove them from office. The old way of staffing administrative agencies, through appointment by elected officials led to the patronage system of the 19th century. The Progressives knew that this would have to give way to a new model: the civil service system. In 1880 after the public horror caused by the assassination of President James Garfield by Charles Guiteau, who had sought a patronage appointment and had been spurned by the President, the Pendleton Act was passed ushering in the modern system of competitive examinations for federal office. Until then any Federal employee could be fired by the president, after that, the overwhelming majority of the decision makers in the administrative state are neither elected by the people nor directly responsible to someone who is elected by the people. They are, literally, unelected bureaucrats.

In his book Congressional Government, Woodrow Wilson reflected his contempt for the American separation of powers system and urged a constitutional change to a parliamentary-style system with centralized power and an expanded federal bureaucracy. He dismissed the president as a mere “clerk of the Congress.” However, over the next two decades, his perceptions about the Presidency changed significantly. Wilson regarded the administration Theodore Roosevelt, the first acknowledged progressive president, as exemplary.

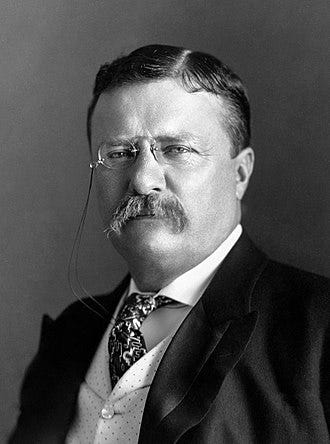

Theodore Roosevelt:

The stature and influence that the presidency has today began to develop with Teddy Roosevelt. Throughout the second half of the 1800s, Congress had been the most powerful branch of government, and although the presidency began to amass more power during the 1880s, Roosevelt completed the transition to a strong, effective executive. He made the President, rather than the political parties or Congress, the center of American politics. Roosevelt did this through the force of his personality and through aggressive executive action. He thought that the President had the right to use any and all powers unless they were specifically denied to him. His approach to presidential power was the new model. Before TR the traditional chief executive dealt with the congressional chieftains to influence policy as it took shape in response to the needs of the times. Instead, the modern president would bypass the ordinary channels of political power and appeal to the public to shape opinion and policy according to his creative vision. His presidency gave the progressive movement credibility, lending the prestige of the White House to welfare legislation, government regulation, and the conservation movement. The desire to make society more fair and equitable, with economic possibilities for all Americans, lay behind much of Roosevelt's program.

Roosevelt also changed the government's relationship to big business. Prior to his presidency, the government had generally given the titans of industry carte blanche to accomplish their goals. One of Roosevelt's central beliefs was that the government had the right to regulate big business in order to protect the welfare of society. However, this idea was relatively untested, although Congress had passed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890, former Presidents had only used it sparingly. In 1902 when the Department of Justice filed suit against the Northern Securities Company, it sent shockwaves through the business community, and gave notice that the status quo had changed. The suit alarmed the business community, which had hoped that Roosevelt would follow precedent and maintain a "hands-off" approach to the market economy. At issue was the claim that the Northern Securities Company—a giant railroad conglomerate created by a syndicate of wealthy industrialists and financiers led by J. P. Morgan—violated the Sherman Antitrust Act because it was a monopoly. In 1904, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the government and ordered the company be dismantled.

Roosevelt kept his attention on the nation's railroads, in part because the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had notified the administration about abuses within the industry. The Elkins Act of 1903 so followed. It ended the practice of railroad companies granting shipping rebates to favored companies, however, the railroads and their cronies were quickly able to undermine the act. Recognizing that the Elkins Act was not effective, Roosevelt pursued further railroad regulation and undertook one of his greatest domestic reform efforts. The legislation, which became known as the Hepburn Act, proposed enhancing the powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission to include the ability to regulate shipping rates on railroads. When Roosevelt encountered stiff resistance in Congress, he took his case directly to the people, going on a speaking tour throughout the western United States. He was ultimately successful when public opinion turned up the pressure on the Senate to approve the legislation. The passage of the Hepburn Act marked the first time a President appealed directly to the people and used the press to help him make his case.

As a Progressive, Roosevelt believed that the government should use its resources and power, to help achieve economic and social justice. When the country faced an anthracite coal shortage in the fall of 1902, because of a strike in Pennsylvania, the President thought he should intervene. As winter approached and heating shortages were imminent, he started to formulate ideas about how he could use the power of the presidency to solve the problem, even though he did not have any authority or precident to end the strike.

Roosevelt summoned the mine owners and the miners to the White House. When management refused to negotiate, Roosevelt told them he would use federal troops to seize the mines and run them as a federal operation. Faced with Roosevelt's plan, the owners and labor unions agreed to submit their cases to a commission and abide by its recommendations. Roosevelt called the settlement of the coal strike a "square deal," inferring that everyone gained fairly from the agreement.

He also revolutionized foreign affairs. It was TR that said “walk softly and carry a big stick” and believed that the US should be the world's policeman. Roosevelt believed that the United States had a global responsibility, and that a strong foreign policy served the country's national interest. When Columbia refused to negotiate a treaty allowing the US to build a canal in Panama, which at the time was part of Columbia, he supported Panamanian rebels against the Columbian government. When the rebels won independence for Panama, Roosevelt swooped in and signed a treaty that gave America control over the entire center of the country. He intervened in Venezuela and the Dominican Republic to “preserve stability” ( read, make it safe for American business) in the region. Roosevelt believed that a large and powerful Navy was an essential component of national defense because it served as a strong deterrent to America's enemies. During his tenure as President, he built the U.S. Navy into one of the largest in the world. In 1907, he proposed sending the fleet out on a world tour. His reasons were many: to show off the "Great White Fleet" and impress other countries around the world with US naval power. In another Foreign Policy first, Roosevelt became the first president to negotiate a peace treaty between two warring countries. This treaty, the Treaty of Portsmouth, ended the Russo-Japanese War and earned Roosevelt the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize.

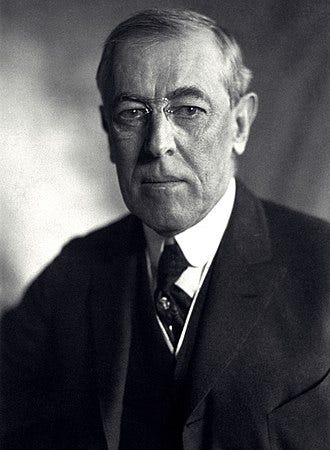

Woodrow Wilson:

Woodrow Wilson took the example of Teddy Roosevelt to heart. He now saw the way forward and knew he could use the precedent set by TR to advance his Progressive agenda even further. He wanted to fundamentally transform the American political landscape and now had both the blueprint and the precedent of TR. In 1912 when President Wilson was inaugurated, he was already hostile to the idea of enacting the Constitution as it was written or intended, and believed, like Roosevelt, that his control of foreign policy was “absolute.” According to Wilson “The President is at liberty, both in law and in conscience, to be as big a man as he can be.”

He began his assault on traditional governance by using The Panic of 1907, a financial crisis that had occurred during the Roosevelt administration. After a special congressional investigating committee, the Pujo Committee, showed the American public the extent to which a handful of banks and corporations controlled the nation's wealth, Wilson pushed for the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. It established twelve regional reserve banks controlled by the Federal Reserve Board, a new federal agency whose members were appointed by the president. This new federal system could adjust interest rates and the nation's money supply. Because it was authorized to issue currency based on government securities and “commercial paper” (the loans made to businesses by banks), the amount of money in circulation would expand or contract with the business cycle. Wilson also pushed through legislation creating the Federal Trade Commission and convinced Congress to create a cabinet-level Department of Labor on March 4, 1913. Wilson strengthened his support among progressives by appointing a former union official, William Wilson, as the first Secretary of Labor.

When the World War I began in 1914, Wilson believed that he could use the war to transform the world in the Progressive mold. According to Wilson, all wars could be prevented with a world association to protect borders, and prevent war for territorial gain. He also believed that it would be a first step on the way to the Progressive utopia of a single monolithic world government. To mobilize public opinion in support of the war, Wilson created the Committee on Public Information headed by George Creel, a muckraking journalist. Creel launched a campaign to sell the war to the American people by sponsoring 150,000 lecturers, writers, artists, actors, and scholars to champion the cause. His “Four-Minute-Men,” were prepared to make a four-minute speech anytime and anywhere a crowd gathered, and by wars end had made more than 755,000 speeches in theaters, lecture halls, churches, social clubs and on street corners all over the nation. In the resulting patriotic fervor, opponents of the war were painted as loafers and even traitors. “Americanization” drives pressured immigrants to become “completely American” by abandoning their cultures. Some states prohibited the use of foreign languages in public. New York State required voters to demonstrate literacy in English (not necessarily a bad idea). Libraries publicly burned German books. Some communities banned playing the music of German musicians such as Bach and Beethoven, and schools dropped German courses from their curriculum. Sauerkraut became “liberty cabbage,” and German measles was renamed “liberty measles.” Some Americans with German names were beaten in the streets and even lynched. To avoid such violence, others anglicized their names. Wilson was also responsible for the passage of the Espionage and Sedition Acts, prohibiting interference with the draft and outlawing criticism of the government, the armed forces, or the war effort. Violators were imprisoned or fined, 1,500 people were arrested for violating these laws. Even suffragettes who refused to stop marching for the right to vote were arrested and thrown in jail. The Post Office was empowered to censor the mail, and more than 400 periodicals were deprived of mailing privileges for periods of time. Leaders and members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), known as “Wobblies,” were especially singled out for attack. In one incident, Justice Department agents raided IWW offices nationwide, arresting union leaders who were sentenced to jail terms of up to twenty-five years. The Supreme Court actually upheld the Espionage and Sedition Acts as constitutional, saying that freedom of speech depends upon the circumstances in which it is done (see Supreme Court section below, for more on this case).

Believing that he could create world peace, Wilson stretched his constitutional wartime powers to their limits. His administration imprisoned political opponents, censored authors, closed newspapers, commandeered whole sectors of the industrial and agricultural economy, all of which were at odds with our history, politics, culture, and Constitution. Wilson’s plan required a mandate from the American people in the 1918 congressional elections. With that in mind, he explicitly attacked his opponents and asked Americans to “sustain” him and “say so in a way which it will not be possible to misunderstand.” They answered, but their answer did not sustain him, Republicans took both houses of Congress easily. Undaunted by this rejection, Wilson negotiated the Treaty of Versailles and took it to the Senate for its ratification. Congressional hearings revealed the unworkability and radicalism of the treaty, with entirely too much power over the daily life of Americans placed in the hands of foreign leaders in Geneva Switzerland. The treaty may still have been ratified if Wilson had consented to protecting the Constitution, but he would not. In fact, Wilson had said he would “consent to nothing” and that “the Senate must take its medicine. and confirm my treaty”. However, under the Constitution, that was simply not the case. The Senate would have its say, and in the end the treaty was not ratified.

Franklin D. Roosevelt:

Maybe the president that did the most to turn the country towards the Administrative State was Franklin D. Roosevelt. When he was elected in 1933 he was given a specific mandate by the American people to rescue the United States from the throes of its worst depression in history. When he accepted the Democratic nomination, FDR had promised a "New Deal" to help America out of the Depression, though the meaning of that program was far from clear. the New Deal was, and remains, difficult to categorize. Even a member of FDR's administration, the committed New Dealer Alvin Hansen, admitted in 1940 that "I really do not know what the basic principle of the New Deal is." Part of this mystery came from the President himself, whose political sensibilities were difficult to measure. Roosevelt certainly believed in the premises of American capitalism, but he also believed that American capitalism, circa 1932, required reform in order to survive. How much, and what kind of, reform was still up in the air. FDR was neither a die-hard liberal nor a conservative, but a Wilsonian Progressive. However, the policies he enacted during his first term sometimes reflected contradictory ideological sources. The New Deal began almost immediately upon Roosevelt's assumption of the presidency. FDR invoked the "analogue of war" as he spurred Congress towards a flurry of legislative activity that became known as the "Hundred Days"—from March to June 1933—in which the new President won passage of numerous bills designed to end the nation's economic troubles. In enacting this agenda, FDR began to remold the role of the federal government in American economic and political life. FDR's immediate task upon his inauguration was to stabilize the nation's banking system. FDR called Congress into emergency session where the legislature enacted, nearly sight unseen, the President's banking proposal. Under this plan, the federal government would inspect all banks, re-open those that were sufficiently solvent, re-organize those that could be saved, and close those that were beyond repair. In 1933 Roosevelt took America off the gold standard, and required all people to turn in to the Federal Reserve all gold coins, gold bullion and gold certificates owned by them to the Federal Reserve by May 1 for the set price of $20.67 per ounce. By May 10, the government had taken in $300 million of gold coin and $470 million of gold certificates. In 1934, the government increased the price of gold to $35 per ounce, effectively increasing the gold on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheets by 69 percent. In addition to removing the gold standard the Banking Act of 1935 gave the country a central banking mechanism for the first time. Which allowed the government to meddle in every aspect of the economy.

Another area of crisis was the state of farming in the US. Many small and family-owned farms had are were about to go bankrupt and Roosevelt saw this as another area where the government could step in. Roosevelt asked Congress to pass the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), which it did in May 1933. FDR and his advisers believed that overproduction had caused gluts in the farm market, dropping prices, and, in turn, sending farmers' incomes plummeting. The AAA aimed to inflate farmers' incomes by offering cash incentives to farmers who agreed to cut production. The AAA originally covered wheat, corn, cotton, hogs, milk, rice, and tobacco, but Congress added new commodities to the program in the ensuing years. More than three million farmers joined the AAA program in its first year, and farm income did increase by more than fifty percent between 1932 and 1935. Despite these impressive gains, the benefits of the AAA too often went to large farm-owners rather than the millions of poor white and black tenant farmers and sharecroppers who lived in abject poverty. Moreover, AAA policies stressed the lowering of production, which meant that crops were plowed under and livestock killed. With many Americans hungry and ill-clothed, critics labeled such policies "utterly idiotic".

Drawing its inspiration from Wilson’s efforts at economic planning during World War I, Roosevelt demanded that Congress pass the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) which they did in June 1933. The NIRA created two new agencies, the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the National Recovery Administration (NRA) which were the cornerstones of the New Deal. There were many other agencies that were created during the New Deal including the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal National Mortgage Association ("Fannie Mae"), and the Federal Housing Administration. The Tennessee Valley Authority was another FDR project that had mixed outcomes. While the TVA brought millions of southern Americans electric power, roads, and jobs in regions that previously had no phones, electric lights, or stable employment, it displaced thousands of people, usually poor farmers, to make way for power plants and dams. In later years, the TVA's dams and power plants wreaked havoc on the environment by spewing pollution.

There were also plenty of critics that arose on the Left and Right to attack Roosevelt and his policies. The American Liberty League founded by former presidential candidate Al Smith, tarred the New Deal as a radical and un-American assault upon the basic principles of capitalism and free enterprise, while Senator Huey Long (D Louisiana), accused FDR of falling captive to American business interests. Long insisted that his "share our wealth" plan of income redistribution would "make every man a king." Dr. Francis Townsend, a California physician, attacked FDR for not doing enough to help elderly Americans and Detroit's Father Charles Coughlin, took to the radio airwaves in 1934 to tell his estimated 40 million listeners that the key to ending the depression was "free silver".

During what became known as the "Second Hundred Days" (June to August, 1935) FDR won passage of a slew of progressive legislation that almost single-handedly dedicated the United States government to providing a minimum level of social and economic protection for all Americans. Three major initiatives represented the administration's turn to the political left: the Works Progress Administration (WPA); the Wagner-Connery National Labor Relations Act (or the Wagner Act, for short); and the Social Security Act. The WPA, for all its efforts, failed to lift the country out of its economic doldrums. The Social Security Act financed its programs through deductions from workers' paychecks, which actually stunted economic growth by lowering consumer purchasing power. Additionally, the programs and benefits of the Social Security Act were not distributed evenly among all Americans. Agricultural workers (who were likely to be black or Latino of both sexes) and domestic servants (often black women) were not eligible for old-age insurance (what is now commonly referred to as "social security"); farm laborers were also ineligible for unemployment insurance. Also since many of these social security programs were administered by state governments, the size of benefits varied widely, especially between the North and the South.

FDR's policies were wildly popular with large segments of the American population, regardless of their ineffectiveness, as his overwhelming victory in 1936 made clear. At his inauguration in 1937, FDR vowed to continue fighting for the nation's underprivileged, the "one-third of the nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished” and also said that he sought "unimagined power" to enforce the "proper subordination" of private power to public power. FDR understood, though, that despite his victory in the 1936 election, his New Deal program was by no means safe. The Supreme Court and a phalanx of Republicans and conservative Democrats had at various times proven hostile to FDR's New Deal. FDR set out in his second term to remove these roadblocks. All too often, however, he encountered stiff resistance.

The Supreme Court topped FDR's list of concerns. Since the Court had ruled the NRA, the centerpiece of the New Deal, unconstitutional, FDR reasoned, it was likely to do the same to subsequent programs, such as the Social Security Act, when they appeared on the Court's docket. Roosevelt's best hope was for the composition of the Court to change. However, older conservative justices opposed to FDR's program refused to retire. Some of the most ardent New Deal supporters surmised that these jurists simply refused to die! So FDR sought a more systematic way to shield his policies from court action.

In early February, 1937, he proposed legislation that would expand the membership of the Court, adding a new justice for every sitting justice over the age of seventy-five. This maneuver would have put six new Roosevelt-appointed justices on the Court, giving FDR a comfortable majority that could be expected to validate the New Deal. Though most of the press erupted in fury, denouncing FDR as a would-be dictator, he had so large a majority in both houses of Congress (5-1 in the Senate, 4-1 in the House), that political commentators expected the bill to pass. However, in late March the Court began to uphold state and federal social legislation in what has been called "the switch in time that saved nine." When the bill finally reached the Senate floor in July, Roosevelt no longer had the votes he needed. He claimed, though, with good reason, that though he had lost the battle he had won the war, for never again did the Court strike down a New Deal law. Scholars differ on why the Court changed, but they almost all agree that what happened in 1937 was nothing less than a "Constitutional Revolution." From that day to today, the Court has not invalidated a single piece of major New Deal legislation regulating business or expanding social rights.

In addition to revamping the Supreme Court, FDR believed that he needed to reform and strengthen the Presidency, and specifically the administrative units and bureaucracy charged with implementing the chief executive's policies. During his first term, FDR quickly found that the federal bureaucracy, specifically at the Treasury and State Departments, moved too slowly for his tastes. FDR often chose to bypass these established channels, creating emergency agencies in their place. "Why not establish a new agency to take over the new duty rather than saddle it on an old institution?" asked the President. "If it is not permanent," he continued, "we don't get bad precedents." FDR would look at other ways to increase his administrative and bureaucratic power. His 1937 plan for executive reorganization called for the President to receive six full-time executive assistants, for a single administrator to replace the three-member Civil Service Commission, for the President and his staff to assume more responsibility in budget planning, and administration for every executive agency to come under the control of one of the cabinet departments. The President's conservative critics pounced on the plan, seeing it as an example of FDR's imperious and power-hungry nature; Congress successfully bottled up the bill. Nonetheless, in 1939, Congress passed a reorganization bill that created the Executive Office of the President (EOP) and allowed FDR to shift a number of executive agencies (including the Bureau of the Budget) to its preview. While FDR did not get the far-reaching result he sought in 1937, the 1939 legislation strengthened the Presidency immeasurably.

Some of the more liberal measures of the New Deal encountered stiff resistance in Congress, often from conservative Southerners within the President's own party. As a result, FDR attempted in 1938 to purge conservative congressional Democrats by supporting their more liberal opponents in the party's primaries. He went after Senators Millard Tydings (Maryland), "Cotton Ed" Smith (South Carolina), and Walter George (Georgia), as well as seven other conservative Democrats. FDR's plan failed miserably; of the ten Democrats he targeted for ouster, only one lost. The others returned to Washington even more antagonistic toward the President. In addition, many other Democrats resented the President's meddling in local affairs.

It was World War II, not the New Deal, that brought an end to the Great Depression. The war sparked the kind of job creation and massive public and private spending that finally lifted the United States out of its economic doldrums. It was a mammoth effort in which the vast majority of America's industrial and human resources were brought to bear. Women and African Americans benefited greatly from this war-time economy, as the former joined the workforce in unprecedented numbers while the latter left the rural and poor South to find industrial employment, as well as voting rights and a less oppressive legal and social system, in the North. Sacrifice was the word of the day. The nation's two main labor union federations, the AFL and the CIO, agreed not to strike. Americans, sometimes begrudgingly, submitted to the federal government's rationing of everything from gasoline to shoes and food. New automobiles, radios, and other big-ticket items were virtually unavailable for purchase. In addition to rationing, the government coordinated the use of raw materials and the production of staple goods. Indeed, during the war the federal government played an even larger role in the functioning of the American economy than it did during the New Deal.

Under FDR, the American federal government assumed new and powerful roles in the nation's economy. Writ large, the New Deal sought to insure that the economic, social, and political benefits of American capitalism were distributed more equally among America's large and diverse populace, but by 1940, the percentage of Americans without jobs remained in double digits and the American people lacked the purchasing power to jump start the economy. FDR also reshaped the American presidency. Through his "fireside chats," delivered to an audience via the new technology of radio, FDR built a bond between himself and the public—doing much to shape the image of the President as the caretaker of the American people. Under FDR's leadership, the President's duties grew to encompass not only those of the chief executive, implementer of policy—but also chief legislator, drafter of policy. In this new role of designing and crafting legislation, FDR required a set of advisers unlike any seen previously in Washington, including a full-time staff devoted to domestic and foreign policies. Before Roosevelt, the federal government was unimpressive relative to the private sector. Under Calvin Coolidge, the last pre-Depression president, its revenues averaged 4 percent of GDP, compared to the 18.6 percent of GDP today. America would never be the same.

This post illustrates one of the biggest problems with the America of today, the power of the president is orders of magnitude more than it was originally designed to be. These three presidents, the two Roosevelts and Wilson, made massive leaps in turning the country away from the traditions of our founding and towards this quasi-America we live in. In my next post, and the last in this series, I will examine the Supreme Court and their role in the expanding administrative state. As always, I hope you enjoy my posts and please share them with anyone who might find them interesting. Until next time, you stay classy Substack!

Chris