Interesting People Throughout History Part II

Today you get three for the price of one, in a salty seafaring tale of the bad luck/good luck dichotomy.

Last time you saw me in your inboxes I delivered Part II of my look at the Baseball Writers of America and the silly decisions they have made regarding post season award voting and election into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Click below if you missed it.

Today, I’m going back to the search for interesting people throughout history. This time I’m going to look at three people who, while seemingly cursed with bad luck, managed to overcome that bad luck (for the most part). The people I’m talking about are; Violet Jessop, Arthur John Priest, and Archie Jewell. You may have heard of Violet, but I’m sure most of you have never heard of Arthur or Archie, but today you will get to meet all three of these interesting people. They all have something specific in common to the three of them. All of them worked aboard the RMS Titanic and survived the sinking, all three also survived the sinking of the HMHS Britannic, the Titanic’s sister ship, during World War I. All three had also been on other vessels that had been severely damaged or sunk. Quite the run of bad luck/good luck. Let’s look at them one at a time.

Violet Jessop

Violet Constance Jessop was born on October 2, 1887, near Bahia Blanca, Argentina. She was the eldest daughter of Irish immigrants William, a sheep farmer, and Katherine Jessop. She was the first of nine children, six of whom survived to adulthood. As a child, contracted tuberculosis, and was not expected to survive. Somehow, she beat the prognosis and made a full recovery. Violet spent much of her childhood caring for her younger siblings. When Jessop was 16 years old, her father died of complications from a surgery and her family moved to England. She attended a convent school and cared for her youngest sister while her mother was at sea working as a stewardess for the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company (RMSPC). In 1908 at the age of 21, when her mother became ill, Violet followed in her mother's footsteps, and applied to be a stewardess with the RMSPC.1 Her first position was aboard the RMS Orinoco sailing between Southampton and ports in Caribbean. In 1911 she left RMSPC and signed on with the White Star Line. She didn’t want to work for White Star initially because she didn’t like the idea of sailing the North Atlantic, because of the weather conditions and the stories of the demanding passengers she had heard. Nevertheless, she became a stewardess on RMS Olympic working 17 hours a day while earning £30 a year (£2,300 or $2,894 in 2025).

Arthur John Priest

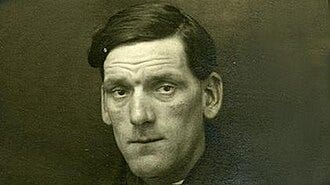

There is much less information about Arthur then what is available for Violet. But I was able to find out that Arthur Priest was born August 31, 1887 in Southampton, Great Britain. He was the son of Harry Priest, a laborer and his wife Elizabeth Garner, and was one of twelve children, eight of which lived to adulthood. In 1905, he began working as a fireman for the RMSPC.2 The firemen were part of what was known as the black gang, a group of 27 men, six firemen, two trimmers (they deliver the coal from the bunkers to the firemen), and the firemen's steward colloquially known as a 'peggy' whose task was to bring food and refreshments to the group. The work was intense and often done while stripped to the waist due to the sustained and intense heat of the furnaces. In 1911 he joined the crew of RMS Olympic still working as a fireman.

Archie Jewell

Again, there is a real lack of firm biographical information on Archie. I was able to find out that Archie Jewell was born December 8, 1888 in Bude, Cornwall, Great Britain. He was, the youngest child of John Jewell, a sailor, and his wife Elizabeth Jewell. He had six older siblings, two sisters and four brothers. His mother died on April 9, 1891. In 1903, at the age of 15, Jewell began working as a seaman on smaller steamships. He joined the White Star Line in 1904 and was assigned to RMS Oceanic as an able seaman.3 He served aboard her for seven years while living in Southampton when not on a voyage.

The Accidents

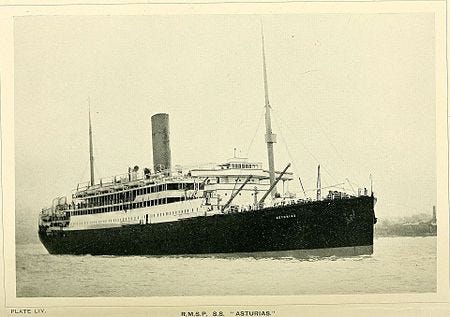

RMS Asturias

In 1908, while Arthur Priest was working on the RMS Asturias, the liner collided with another vessel. No one was killed, but the damage was significant and the ship barely made it back to port.

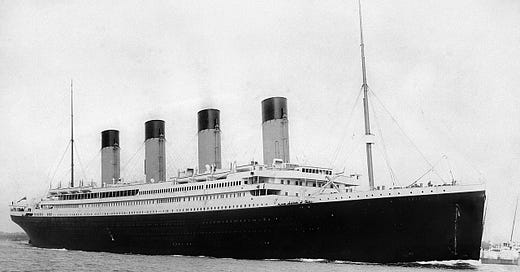

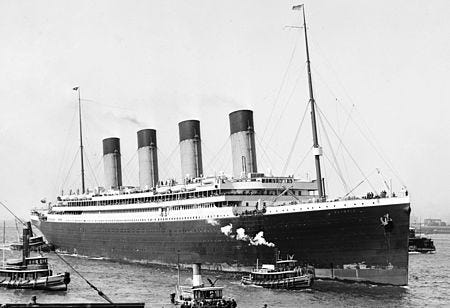

RMS Olympic

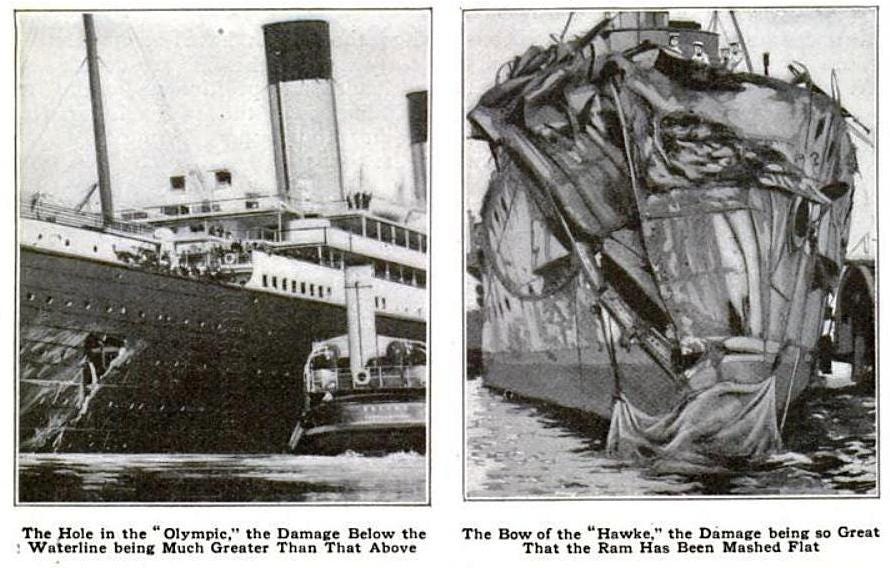

On September 20, 1911, shortly after Violet Jessop joined the crew of Olympic and with Arthur Priest down in the boiler room, a collision took place between RMS Olympic and HMS Hawke, a Royal Navy Edgar class cruiser. The two ships were running parallel to each other travelling through the Solent.4

As Olympic turned to starboard, the wide radius of her turn took Commander William Frederick Blunt, the commanding officer of the Hawke, by surprise, and he was unable to avoid the collision. The Hawke's bow, which had been designed to sink ships by ramming them, sliced into Olympic's starboard side near the stern, tearing two large holes in Olympic's hull, above and below the waterline. This resulted in the flooding of two of her watertight compartments and a twisted propeller shaft. Olympic settled slightly by the stern, but in spite of the damage was able to return to Southampton under her own power. No one was killed or seriously injured, in the accident, but HMS Hawke suffered severe damage to her bow and nearly capsized. However, the accident caused a delay in the completion of Titanic, because one of her propellers was used to fix Olympic.

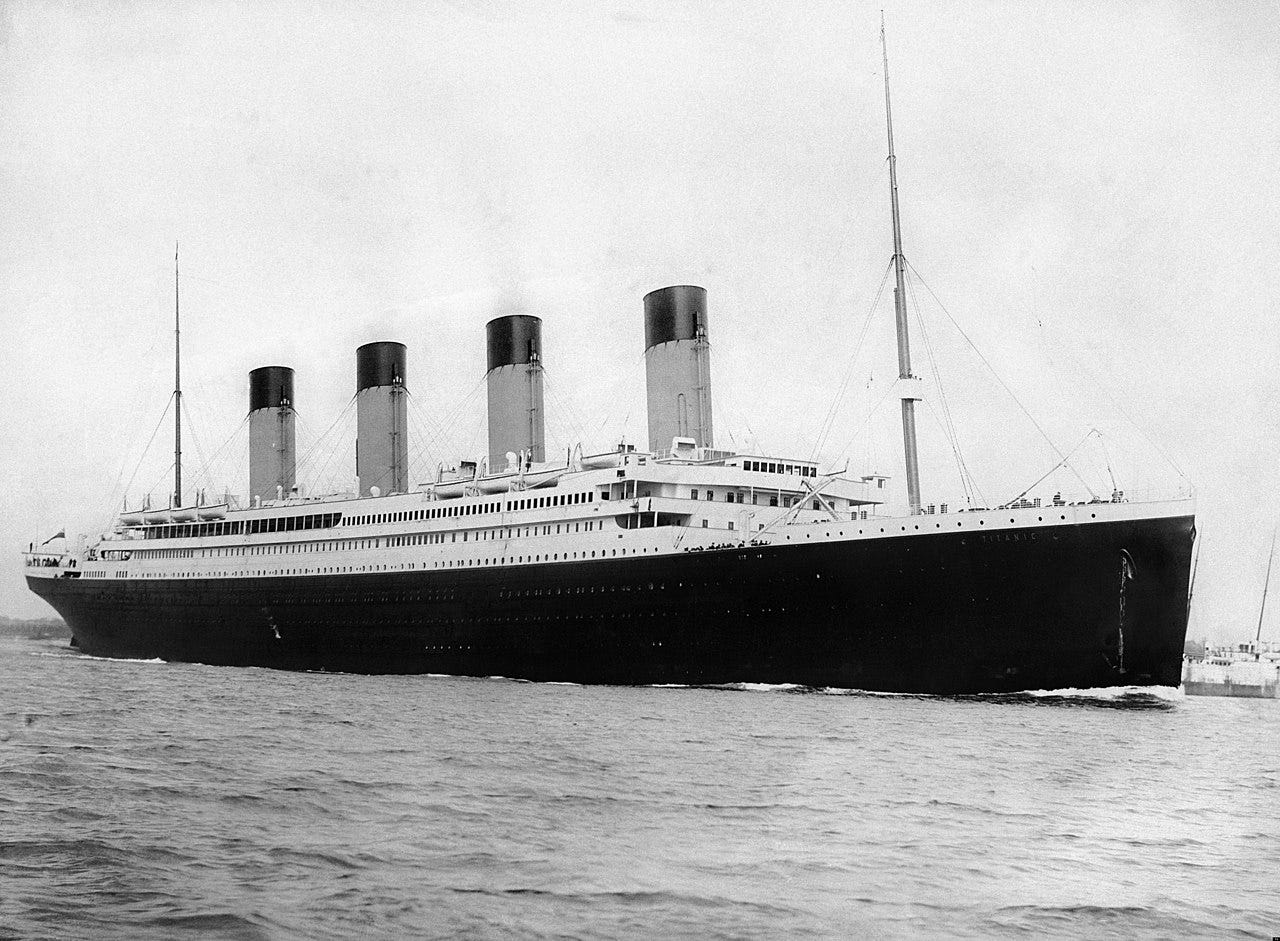

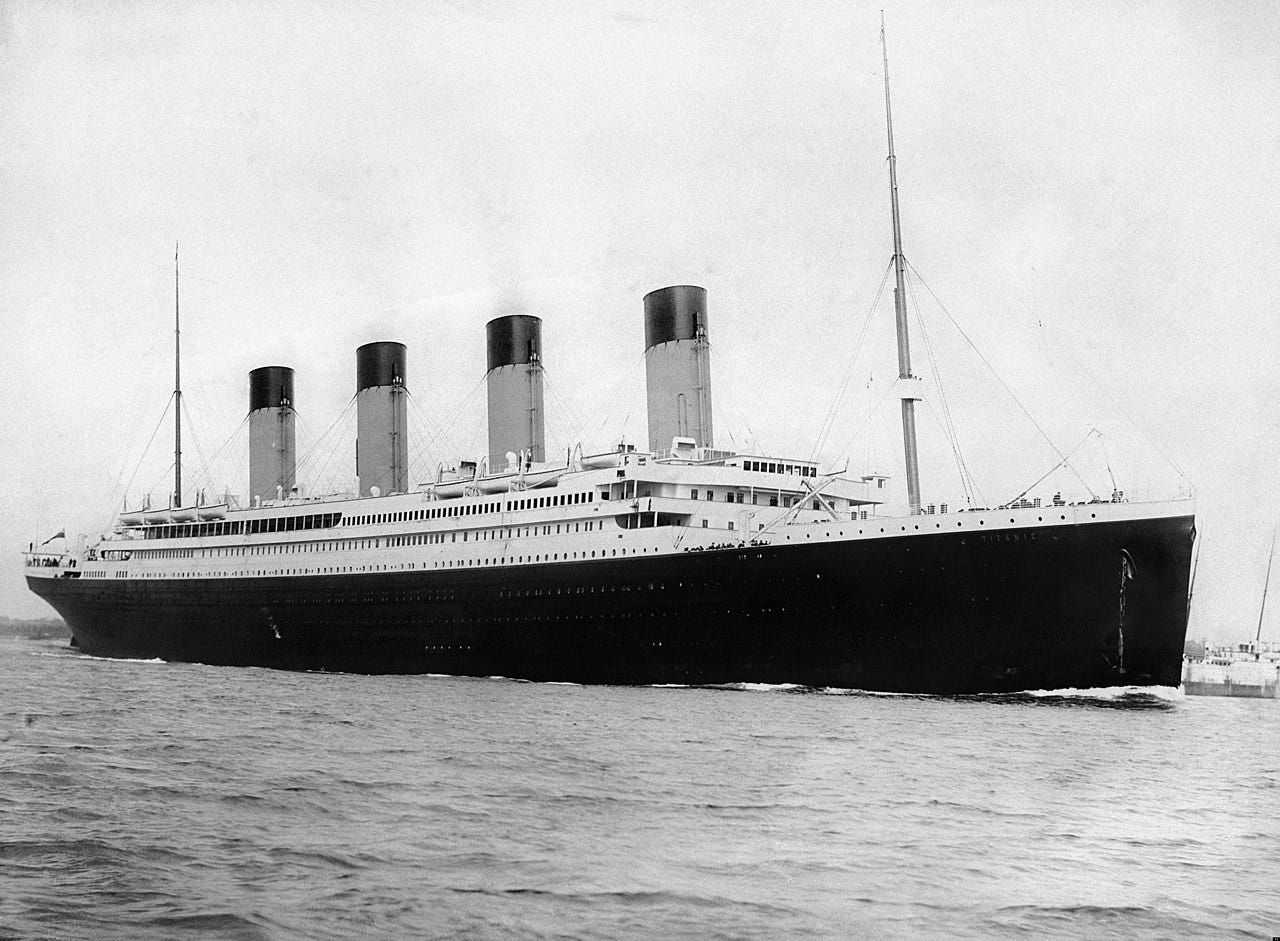

RMS Titanic

That delay allowed White Star to change the design of Titanic, following lessons learned from the Olympic's cruises. This made Titanic “the ship” to sail on, and Violet's friends wanted her to transfer to Titanic and sail with them. She was reluctant to transfer because she was happy working on Olympic, but as more details of Titanic came out, specifically the crew quarters, she was convinced and transferred to the “unsinkable” ship. We all know what happened early in the morning of April 15, 2912, during the maiden voyage of Titanic, but our three brave souls all had roles to play in the tragedy.

Archie Jewell was in the crow’s nest on lookout duty from 8:00 pm to 10:00 pm, at 9:00 pm he received a call from the bridge telling him to keep a sharp lookout for all ice, big and small. When he was relieved by the next shift, he had not seen any ice. He went to sleep in his bunk (he was scheduled for another watch at 2:00 am), and was awakened by a crash. When he went up on deck he saw ice on the deck from the iceberg that had doomed the ship. He was ordered to be part of the crew of Lifeboat #7 which was lowered into the icy Atlantic at 12:45 am from the starboard side of the vessel. Since most of the passengers and crew still believed the ship would not sink, when the lifeboat was launched at 12:45 am, it contained 28 people even though it had a capacity of 65 people.

Violet Jessop’s part in that terrible night might be even more strange. After it became apparent the ship was going to sink, some of the 42 female crew were ordered on deck to be an example on how to act for the hundreds of non-English speaking passengers to follow. Violet was one of those picked. When the lifeboats were being loaded many of the genteel women on board refused to get in the boats, thinking they weren't safe. Once again, Violet was chosen to be the example and was put into Lifeboat #6. Just as the boat was being lowered another crew member dropped a bundle in Violet's lap and yelled “keep an eye on that”, it was a infant wrapped tightly in blankets. After being taken aboard Carpathia, a woman ran up to Violet Jessop and grabbed the baby she was still clutching to her lifevest and ran off. Jessop said later:

“I was too frozen and numb to think it strange that this woman had not stopped to say “thank you”.”

At the same time, down in the six boiler rooms of Titanic, the approximately 176 firemen on board, disregarded their own safety, and stayed below deck, keeping the steam-driven electric generators running for the radiotelegraph, lighting, and water pumps. When it became clear the ship had only a little time left, the firemen were given the order to evacuate. Some chose to stay behind and keep feeding the furnaces until the last moment. Arthur Priest was one of the firemen that left. By the time he made it up on deck, the passengers and crew were in a panic, the bow of the ship was already under water and most of the lifeboats had already been launched. He had to jump in the water and swam for a while, clad only in shorts and a life vest. He was rescued from the water by Lifeboat #15, the last boat launched from the starboard side at 1:35 am. That lifeboat was almost full with 68 people on board. He injured his leg in the escape, and by the morning when the survivors were picked up by the Carpathia was suffering from frostbite on his toes. Luckily for him, or not, he did not lose any toes.

It is fairly strange that these three crew members survived, since 75% of the crew perished (212 of 908). After the sinking there was a inquest conducted by the British Wreck Commissioner on behalf of the British Board of Trade. The inquiry was overseen by High Court judge John Bigham , 1st Viscount Mersey. It was held in London from May 2, to July 3, 1912. The hearings took place mainly at the London Scottish Drill Hall. Mr. Jewell was the first person questioned during the inquest, he answered 331 questions in all, and was given a word of thanks from Lord Mersey for his candor and his answers. Neither Ms. Jessop nor Mr. Priest were questioned.

RMS Alcantara

In April 1915, with World War I in full swing, the British Admiralty requisitioned four “A"-Series” ships from the RMSPC.5 The Alcantara, the Avon, the Arlanza and the Atlantis were converted into armed merchant cruisers. They were armed with six 150 mm (6-inch) guns, anti-aircraft guns and depth charges. On April 17, 1915, they were commissioned into the Royal Navy and assigned to the 10th Cruiser Squadron. The 10th Squadron joined the Northern Patrol, part of the blockade of Germany. The Squadron patrolled about 200,000 square miles of the North Sea, Norwegian Sea and Arctic Ocean to prevent German ships from leaving the North Sea.

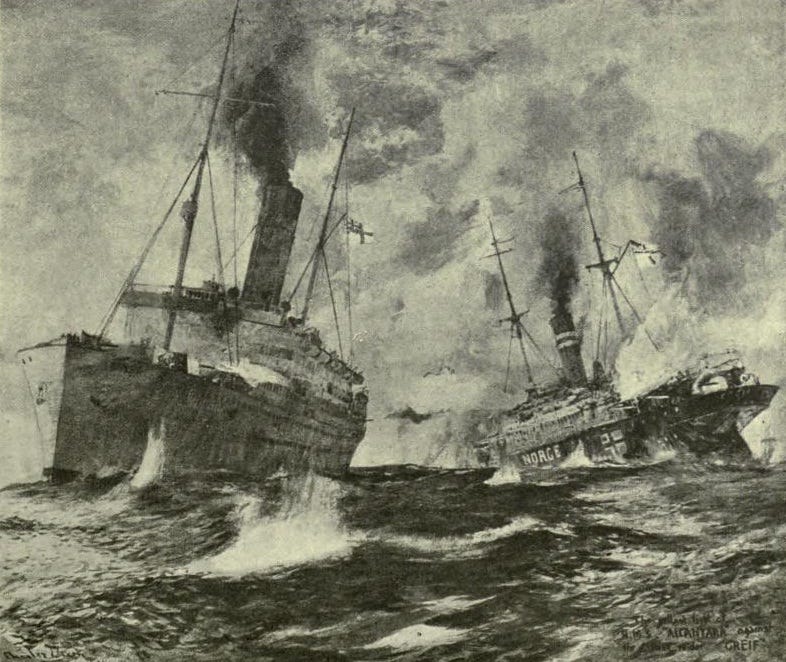

At 8:45 am on February 29, 1916, HMS Alcantara, along with the HMS Andes was steaming north-north-east near its patrol line, when lookouts spotted smoke off the port beam. The captain, Thomas Wardle maneuvered closer to identify the source of the smoke. Unbeknownst to him, the smoke was from SMS Greif, a converted merchant raider armed with four 5.9 inch guns, two 4 inch guns and two torpedo tubes.6 A few minutes later Andes signalled "Enemy in sight north-east 15 knots". Wardle ordered Alcantara to turn north at maximum speed and soon sighted a ship with one funnel, flying Norwegian flags. Another message from Andes described a two-funnelled ship and the identity of the ship in sight remained doubtful. A few minutes later, Andes was seen to starboard, apparently steaming north-east at speed, as if in pursuit. Before joining the chase, Wardle decided to examine the unknown ship, went to action stations and fired two blanks to force it heave to.

By 9:20 am, Wardle had received a signal by the Andes that it had altered course to the south-east, which only added to the confusion, because the ship he was investigating could not be the one being pursued by the Andes. The lookouts on the Alcantara could see the Norwegian flag and the name Rena on the stern, the ship looked authentic. A boat was lowered from Alcantara when it was about 1,000 yards astern to check the ship's particulars, since the Admiralty had been informed about the voyage of the Rena. Wardle signalled the developments to the Andes, and George Young, captain of the Andes, replied with "This is the suspicious ship". As the message was being read, a gun at the stern of the "Rena" was unmasked and flaps fell down along the sides, revealing more guns. The Greif opened fire, hitting the boat containing the boarding party and damaging Alcantara's steering gear before the British ship could reply. Alcantara's gunners opened fire and the ship closed with the raider as it began to get under way. For about fifteen minutes the ships exchanged fire. The Andes opened fire when she arrived and Greif was soon obscured by a pall of smoke. The German gunners ceased fire and boats full of survivors were seen pulling away from the ship. The Alcantara had been hit by a torpedo, was badly damaged and was listing to port. Wardle ordered the crew to abandon ship, and by 11:00 am, the list was so bad the Alcantara was on the brink of capsizing. At 11:10 it turned over and slipped beneath the waves, it sank with 69 members of her crew. The cruiser HMS Comus and the destroyer HMS Munster, had seen the signals from Andes and sailed south. They arrived as the action ended, and began to rescue the crew of the Alcantara. Comus and Andes moved closer to the wreck of the Greif and sank it with gunfire; about 220 men of its crew of 360 were rescued. Arthur Priest was in the boiler rooms and there he stayed until the abandon ship order was given. He was in a lifeboat that was picked up by the HMS Munster.

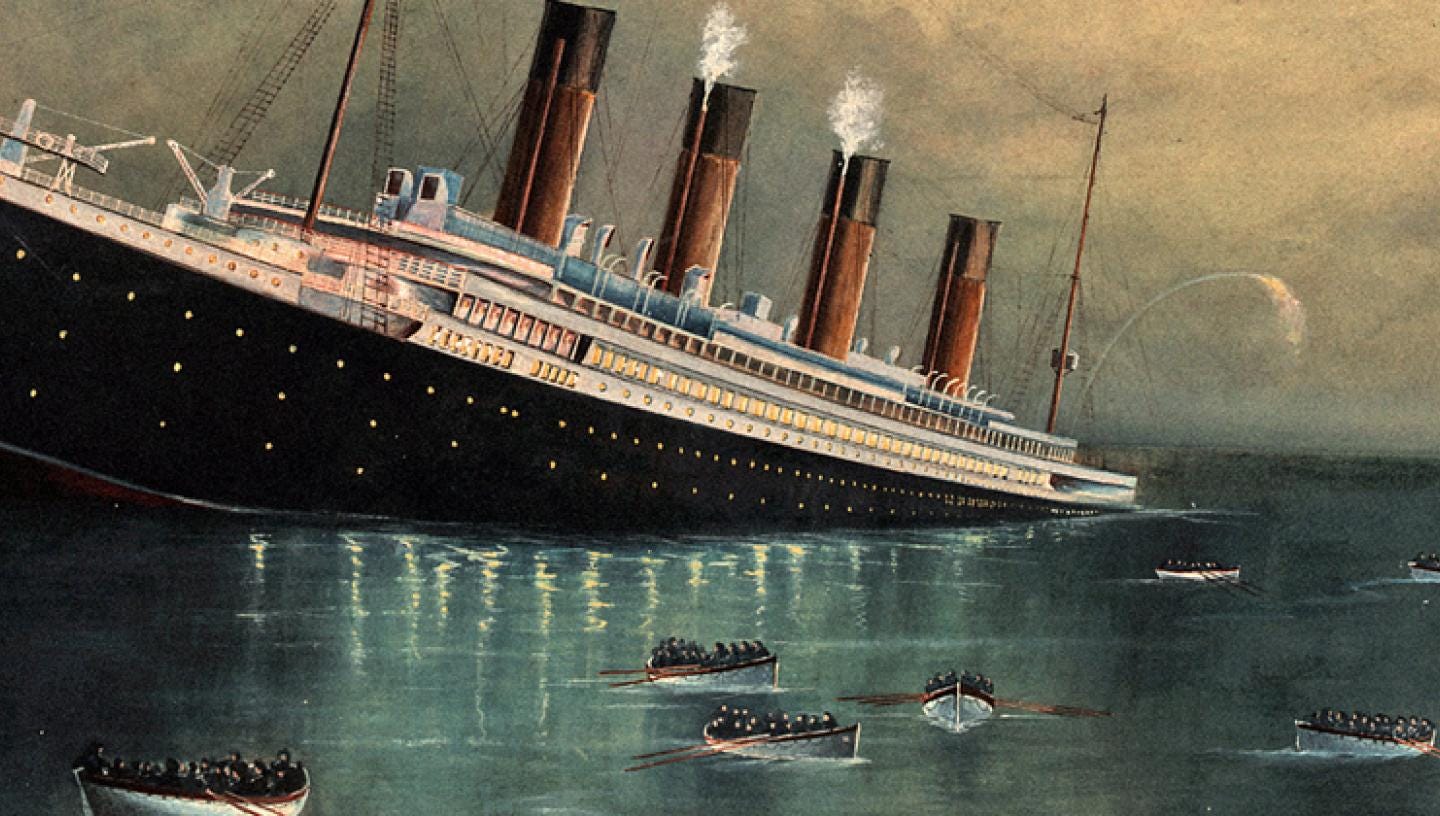

RMS Britannic

Since the loss of this ship is not nearly as well known as her sister, I have written a more detailed account of the time leading up to the incident and the actual sinking itself.

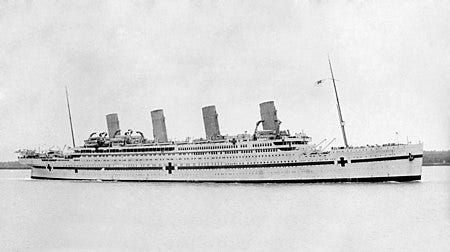

Because of the sinking of the Titanic, the completion of the last ship in the three ship class, the RMS Britannic, was delayed while safety concerns were addresses and facilities upgraded. Therefore, Britannic was launched February 26, 1914, with fitting out beginning immediately. In August 1914, before Britannic could commence transatlantic service between New York and Southampton, World War I broke out. Immediately, all British shipyards with Admiralty contracts were given available raw materials priority. All construction on civil contracts, including Britannic, were slowed. The naval authorities requisitioned a large number of ships as armed merchant cruisers, troop transports or hospital ships. The Admiralty paid the companies for the use of their ships but the risk of losing a ship in naval operations was high. The larger ocean liners were not initially taken for naval use, because smaller ships were easier to operate. Olympic returned to Belfast, while work on Britannic continued slowly. The need for increased tonnage grew critical as naval operations extended to the Eastern Mediterranean. In May 1915, Britannic completed mooring trials of her engines, and was prepared for emergency entrance into service with as little as four weeks' notice. The same month also saw the first major loss of a civilian ocean liner when Cunard's RMS Lusitania was torpedoed near the Irish coast by U-20.7

The following month, the Admiralty decided to use recently requisitioned passenger liners as troop transports in the Gallipoli campaign. The first to sail were Cunard's RMS Mauretania and RMS Aquitania. As the Gallipoli landings proved to be disastrous and the casualties mounted, the need for large hospital ships for treatment and evacuation of wounded became apparent. Aquitania was diverted to hospital ship duties in August (her place as a troop transport would be taken by Olympic in September). Then on November 13, 1915, Britannic was requisitioned as a hospital ship from her storage location at Belfast. Repainted white with large red crosses and a horizontal green stripe, she was renamed HMHS (His Majesty's Hospital Ship) Britannic and placed under the command of Captain Charles Bartlett. In the interior, 3,309 beds and several operating rooms were installed. The common areas of the upper decks were transformed into rooms for the wounded. The cabins of B Deck were used to house doctors. The first-class dining room and the first-class reception room on D Deck were transformed into operating rooms. The lower bridge was used to accommodate the lightly wounded. The medical equipment was installed on December 12, 1915, and she was declared fit for service.

Britannic was assigned a medical team consisting of 101 nurses, 336 non-commissioned officers and 52 commissioned officers as well as a crew of 675 people. On December 23, she left Liverpool bound for the port of Mudros on the island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea. There were several other ships on the same route including the Mauretania, Aquitania and her sister ship Olympic. The group made a stop in Naples to restock coal and take on water, before continuing to Mudros. All the vessels picked up the mounting casualties from the Gallipoli campaign, and returned to Great Britain. After she returned, she spent four weeks as a floating hospital off the Isle of Wight.

The Britannic made two more uneventful voyages to Mudros and back. By June 6, 1916, her military service was over and she returned to Belfast to be transformed back into a transatlantic passenger liner. The British government paid the White Star Line £75,000 (£8.3 million or $10.4 million in 2025) to compensate the company for the conversion. The work took place for several months before she was recalled into military service on August 26, 1916. Britannic returned to the Aegean Sea for a fourth and fifth voyage between September 24, and November 10, 1916.

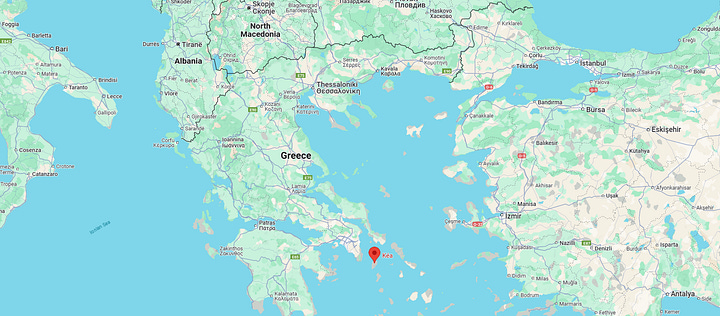

After completing five successful voyages, Britannic departed Southampton for a sixth voyage to Lemnos on November 12, 1916. There were 673 crew, 315 members of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 77 nurses, and the captain, a total of 1,066 souls on board. She arrived at Naples on November 17, but a storm kept her in port until the 19th, when Captain Bartlett decided to take advantage of a brief break in the weather and continue. By the morning of November 21, Britannic was steaming at full speed into the Kea Channel, between Cape Sounion and the Island of Kea. At 08:12 am European Eastern Time, Britannic was rocked by an explosion after hitting an anti-ship mine. The mines had been planted in the Kea Channel on October 21, U-73.

The reaction in the dining room was immediate; doctors and nurses left instantly for their posts. However, further aft, the explosion was not felt as strongly and many thought the ship had hit a smaller boat. Captain Bartlett and Chief Officer Robert Hume were on the bridge at the time and the gravity of the situation was soon evident. The explosion was on the starboard side, between holds two and three, and damaged the watertight bulkhead between hold one and the forecastle. The first four watertight compartments were filling rapidly with water, the fireman’s tunnel connecting the firemen's quarters in the bow, with boiler room six was seriously damaged, and water was flowing into that boiler room. On the bridge, Captain Bartlett was already considering efforts to save the ship. Only two minutes after the blast, boiler rooms five and six had to be evacuated. In ten minutes, Britannic was roughly in the same condition Titanic had been in, one hour after hitting the iceberg. Bartlett gave the order to prepare the lifeboats, but he did not allow them to be lowered into the water at this time.

Captain Bartlett gave the order to turn starboard towards the island of Kea in an attempt to beach her. The steering gear had been knocked out by the explosion, which eliminated steering by the rudder and the effect of Britannic's starboard list as well as the weight of the dead rudder made attempts to navigate the ship under her own power difficult. The captain ordered the port shaft driven at a higher speed than the starboard side, which helped the ship move towards Kea. Bartlett ordered the watertight doors closed, sent a distress signal. An SOS signal was immediately sent out and received by several ships in the area, among them HMS Scourge and HMS Heroic, but Britannic heard nothing in reply. Unknown to either Bartlett or the ship's wireless operator, the force of the explosion had caused the antenna wires slung between the ship's masts to snap. This meant that although the ship could still send out transmissions, she could no longer receive them. At the same time, the hospital staff prepared to evacuate.

Along with the damaged watertight door of the firemen's tunnel, the watertight door between boiler rooms five and six failed to close properly, and now water was flowing into boiler room five. Britannic could stay afloat, while motionless, with her first six watertight compartments flooded but at this point she had reached her flooding limit.8 The next crucial bulkhead between boiler rooms five and four and its door were undamaged and should have guaranteed the ship's survival. However, there were open portholes along the lower decks. The nurses had opened most of those portholes to ventilate the wards, against standing orders. As the ship's list increased, water reached this level which submerged the portholeds within minutes of the explosion. Water began entering the ship behind the final watertight compartment between boiler rooms five and four, and the ship was doomed.

While Bartlett continued his desperate maneuver, Britannic's list steadily increased. Fearing that the list would become too large to launch, some crew decided to launch lifeboats without waiting for the order to do so. Two lifeboats were put onto the water on the port side by Third Officer Francis Laws. These boats were drawn towards the still-turning, partly surfaced propellers. Bartlett ordered the engines stopped, but before this could take effect, the two boats were drawn into the propellers, completely destroying both and killing 30 people. Bartlett was able to stop the engines before any more boats were lost.

By 8:50 am, most of those on board had escaped in the 35 successfully launched lifeboats. At this point, Bartlett concluded that the rate at which Britannic was sinking had slowed so he called a halt to the evacuation and ordered the engines restarted in the hope that he might still be able to beach the ship. At 9:00 Bartlett was informed that the rate of flooding had increased because of the ship's forward motion and that the flooding had reached D-deck. Realizing that there was now no hope of reaching land in time, Bartlett gave the final order to stop the engines and sounded two final long blasts of the whistle, the signal to abandon ship. As water reached the bridge, he and Assistant Commander Dyke walked off onto the deck and entered the water, swimming to a collapsible boat from which they continued to coordinate the rescue operations.

Britannic gradually capsized to starboard, and the funnels collapsed one after the other as the ship rapidly sank. By the time the stern was out of the water, the bow had already slammed into the seabed, since Britannic's length was greater than the depth of the water, the impact caused major structural damage to the bow before she slipped completely beneath the waves at 9:07, 55 minutes after the explosion. Unlike with the Titanic, ships were on the scene to assist within two hours. Another major difference between the two accidents was the temperature of the water. In 1912 the icy North Atlantic was 28°, In the balmy Aegean it was 68°. In total, out of the 1,066 people on board, 1,036 people survived the sinking. Thirty people lost their lives in the disaster.

Violet Jessop was a stewardess with nursing duties for the British Red Cross tending to the wounded soldiers on board the Britannic. She stayed at her post helping the wounded get into lifeboats, but did not find a place for her on one. According to her account:

“I leapt into the water, but was sucked under the ship’s keel, which struck my head. She dipped her head a little, then a little lower and still lower. All the deck machinery fell into the sea like a child's toys. Then she took a fearful plunge, her stern rearing hundreds of feet into the air until with a final roar, she disappeared into the depths, the noise of her going resounding through the water with undreamt-of violence. I escaped, but years later when I went to a doctor because of lots of headaches, he discovered I had once sustained a fracture of the skull.”

Archie Jewell was on duty as a lookout when the mine exploded. He came down from the crow’s nest and manned a lifeboat, just like on Titanic. This time, however, it was clear from the outset that the ship was going to sink and the boats were filled and launched in good order. He was picked up by the HMS Scourge along with 338 other survivors.

Arthur Priest was in one of the boiler rooms along with the rest of the black gang and stayed at his post shoveling coal into the furnace until Captain Bartlett called for the engines to be stopped for good, and for the crew to abandon ship. In a letter to his sisters he described his escape:

"... most of us jumped in the water but it was no good we was pulled right in under the blades. I shut my eyes and said goodbye to this world, but I was struck with a big piece of the boat and got pushed right under the blades and I was going around like a top. I came up under some of the wreckage and everything was going black, when someone on top was struggling and pushed the wreckage away so I came up just in time, I was nearly done for. There was one poor fellow drowning and he caught hold of me but I had to shake him off so the poor fellow went under."

He was eventually picked up by HMS Heroic along with 494 people.

SS Donegal

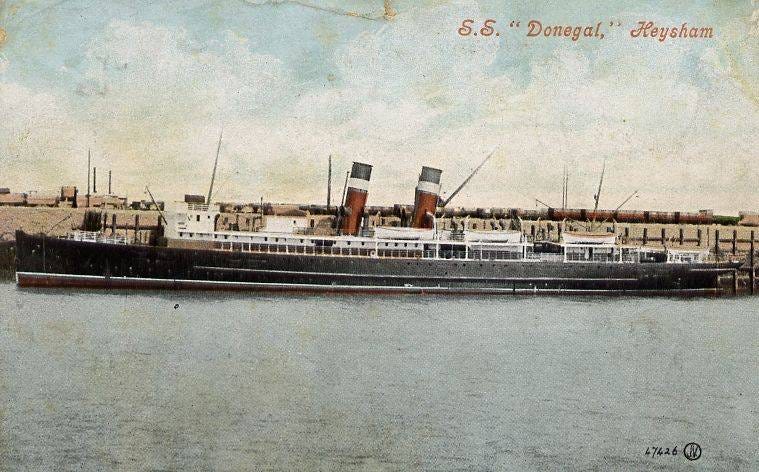

SS Donegal was one of numerous ferries, requisitioned from railway companies, that were converted into ambulance ships to carry wounded personnel from France back to Great Britain. On March 1, 1917 a German submarine tried to attack Donegal but the steamer managed to outrun her. On April 17, 1917, the Donegal left the French port of Le Havre with a Royal Navy escort, bound for Southampton carrying 610 wounded soldiers and 70 crew. She was about 58 miles south of her destination, when she was attacked and torpedoed by minelaying submarine UC-21. She sank quickly with the loss of 29 wounded British soldiers and 12 of her crew.

Arthur Priest, who has to have the best bad luck ever, was once again, down in the boiler room shovelling coal. Once again, he managed to escape, but I was unable to find any information as to how he did it or how he survived.

Afterword

Archie Jewell was also on board the Donegal but this time his luck had run out. He was one of the twelve crew members lost in the sinking. His body was never recovered, he was 28 at the time.

In 1920, after World War I, Violet Jessop returned to work for White Star, before joining Red Star Line Jessop went on two cruises around the World on the company's flagship, Belgenland. She ended her career by going back to RMSPC (which had shortened their name to Royal Mail Line). In 1936, when Violet was 36, she married John James Lewis, a fellow White Star Line steward. They divorced around a year later. In 1950, she retired to Great Ashfield in Suffolk. Jessop died of congestive heart failure in 1971 at the age of 83.

Arthur Priest's life is an amazing story of human endurance. He worked his entire life in extraordinary conditions in the belly of the ship, where fires and explosions were common. He was often at the very worst part of a vessel from which to escape and yet he survived an astonishing litany of torpedoes, mines, icebergs and collisions to live out his days spinning tales in the pubs of Southampton. In 1917, Arthur was awarded the Mercantile Marine Ribbon for his service in World War I. After the sinking of SS Donegal, Priest retired from his job as a stoker. He lived out the rest of his days in Southampton, with his wife Annie. He claimed that "no one wished to sail with him after these disasters." He died in 1937, on dry land. Truly, the name "unsinkable" applied rather better to him than it did to the mighty Titanic.

As I said in the beginning of this post, I was giving you three people for the price of one. I think Violet, Arthur and Archie are remarkable people that led exciting lives, revolving around some of the most important events of the early 20th century. Were they lucky or unlucky? Hard to say, they were lucky to live through all those disasters but unlucky to keep finding themselves in those situations. Obviously Archie wasn’t as luck as Arthur but he still lived through two major sinkings. I hope you all have enjoyed this look at three interesting people from history. Please share this with Next time I’ll be starting my Detroit Tigers 2025 season preview and predictions.

Chris

A stewardess on the larger transatlantic passenger ships would primarily be responsible for attending to the personal needs of passengers in their cabins, including serving meals, maintaining cleanliness, assisting with clothing needs, and generally ensuring their comfort throughout the voyage, essentially acting as a personal attendant on board the ship; this could involve tasks like bringing drinks, tidying up cabins, and responding to passenger requests.

A fireman in the British Merchant Navy is a seaman that is part of the Engineering Department. Their duty was to tend the fire of the boilers powering a steamship. The job is hard physical labor consisting mostly of shoveling coal into the firebox of the vessel’s boilers.

An Able Seaman (AB) is a seaman that is part of the Deck Department of a merchant ship with more than two years experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty”. An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination of these roles.

The Solent is a strait between the Isle of Wight and mainland Great Britain. The ports of Southampton and Portsmouth lie inland of its shores. It is about 20 miles long and varies in width between 2-1/2 and 5 miles.

The Admiralty was a department of the United Kingdom Government responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964.

SMS means Seiner Majestat Schiff in German. It is the same as His Majesty’s Ship in English. It was used for all German naval vessels until the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1918.

Passengers had been notified before departing New York of the danger of voyaging into a war zone in a British ship, but the attack itself came without warning. U-20 fired a single torpedo at the ship. After the torpedo struck, a second explosion occurred inside the ship, which then sank in only 18 minutes. There were only 763 survivors out of the 1,960 passengers and crew and 128 of the dead were American citizens.

After the loss of Titanic, the number of watertight bulkheads was increased from four to five and they rose three decks higher on Britannic.