In my last post I covered the period in the history of Israel, from 1956 until early 1967. Click the link below if you missed it.

This time I will discuss the history and events leading up to the Six Day War. Historians have compared the Six Day War to a schoolyard fight. Each side was being restrained by a stronger ally and at the same time, fighting against that restraint, all the while spewing provocative language. It seems like both sides were being carried along by forces they could not control towards a war that neither side really wanted. It is a very interesting time and observed from the outside seemed like a very preventable conflict.

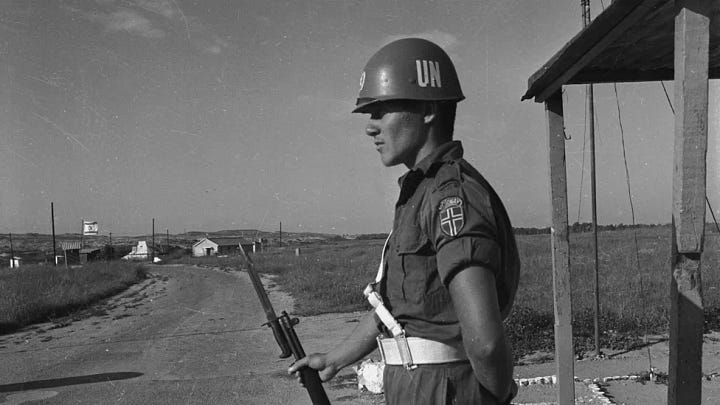

After the Suez crisis, the situation in the Middle East changed dramatically. The United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) was stationed in the Sinai peninsula, separating Egyptian and Israeli forces and ensuring compliance with the 1949 and 1956 armistice agreements. In 1958, Egypt and Syria agreed to a political and military union known as the United Arab Republic, placing Israel in the middle of their two biggest rivals, who now had a much closer relationship and level of cooperation. Jordan was also trying to navigate the minefield of relations in the region. And hovering over everything like a dark storm cloud was the Cold War, this contest of wills raged on, with the US and USSR vying for influence in every area of the world.

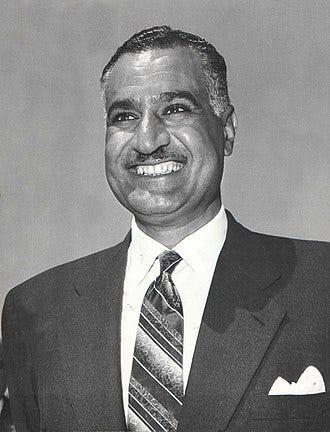

In the years following Sinai, when the situation was supposed to be stabilizing, there were numerous border clashes between Israel, Syria and Jordan. Clashes that had killed 60 Israelis since 1957. In November 1966, in response to PLO guerilla activity, including a mine attack that left three dead, the IDF attacked the village of al-Samu in the West Bank. After a battle that saw 19 Jordanians killed and 150 wounded. King Hussein of Jordan criticized Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser for failing to come to Jordan's aid, and "hiding behind UNEF skirts".

The issue of water sharing from the Jordan–Yarmuk river system would also be a major problem between Israel, Syria and Jordan. Small scale water-related skirmishes had occurred since the 1949 agreements. In July 1953, when Israel began construction of an intake for its National Water Carrier at the Daughters of Jacob Bridge in the demilitarized zone north of the Sea of Galilee, Syrian artillery units opened fire on the construction site. A majority of the UN Security Council (the only “no” vote was the USSR) voted for the resumption of work by Israel, but the intake was moved to a site on the Sea of Galilee.

In 1955, the Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan, otherwise known as the Johnston Plan, was accepted by the technical committees of both Israel and the Arab League, but both the General Assemblies of the Arab League and Israel failed to ratify the plan. The fact that neither Israel nor the Arab League ratified the plan was not considered critical, because both sides seemed to adhere to the technical details of the agreement. Israel completed the National Water Carrier project in 1964, with an initial diversion capacity of 960 million square feet, well within the limits of the Johnston Plan. Nevertheless, the Arab states were not prepared to coexist with a project which would be a major benefit to Israel’s economic growth. In January 1964 an Arab League summit meeting in Cairo decided to deprive Israel of 35% of the National Water Carrier capacity, by a diversion of the headwaters of the Jordan River to the Yarmuk River. The scheme was only marginally feasible, as it was technically difficult and expensive. After that announcement, Israel declared that they viewed the diversion project as an infringement on its sovereign rights. In 1965, there were three notable border clashes connected to the diversion plan, starting with Syrian shootings of Israeli farmers and army patrols, followed by Israeli tanks and artillery destroying the Arab heavy earth moving machines that were used for the diversion plan.

The Armistice Agreement had also established demilitarized zones (DZ) on the Israel-Syria border. However, Israel gradually took over portions of the zones, evicting Arab villagers and demolishing their homes. Israel regarded the de-militarized zones in the north as part of their sovereign territory, but that view was not sanctioned by the UN. The southernmost, and the largest of the DZs, stretched from the southeastern shore of the Sea of Galilee east to the Yarmuk River where the borders of Israel, Jordan and Syria converge. In April of 1967, Syria attacked Israeli tractors working in the DZ area on two separate occasions. When the tractors returned on the morning of April 7, 1967, the Syrians opened fire with light weapons. The Israelis responded by sending in armor-plated tractors to continue ploughing, resulting in a further exchanges of fire. The resulting tit-for-tat escalated, leading to heavy machine guns, mortars, tanks and artillery exchanging fire, in what was described as "a dispute over cultivation rights in the demilitarized zone south-east of Lake Tiberias.” Without advance planning or prior approval of the Ministerial Committee on Security. Israeli aircraft bombed Syrian positions and the Syrians responded by heavily shelling Israeli border settlements. Israeli jets retaliated by bombing the Syrian village of Sqoufiye, destroying around 40 houses. In response to that bombing, Syrian artillery fired over 300 shells on kibbutz Gadot in 40 minutes. The "incident" had also escalated into a full-scale aerial battle over the Golan Heights, with Israeli Mirage IIIs battling Syrian MiG-21s. The dogfights resulted in the loss of six MiGs and a group of IAF Mirages making a provocative flight over Damascus. The United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) attempted to arrange a ceasefire, but Syria declined to co-operate unless Israeli agricultural work was halted.

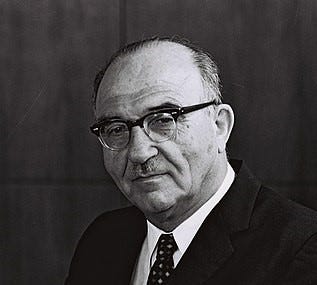

Speaking to a Mapai party meeting in Jerusalem on May 11, Prime Minister of Israel Levi Eshkol warned that Israel would not hesitate to use air power on the scale of April 7, in response to continued border terrorism. On the same day Israeli UN ambassador Gideon Rafael presented a letter to the Security Council warning that Israel would "act in self-defense as circumstances warrant".

On May 13, at the end of a visit to the Soviet Union by Egyptian Vice President Anwar Sadat, Soviet President Nikolai Podgorny, relayed a Soviet intelligence report that Israeli troops were massing along the Syrian border. On May 14, Nasser sent his chief of staff, General Mohamed Fawzi, to Syria in order to verify the Soviet warning. Fawzi reported that there were no visible indications that the Israelis were sending any troops at all to the Syrian border. However, while Fawzi was in Syria, Soviet Ambassador Dmitri Pozhidaev handed a telegram to Nasser from Podgorny stating that the KGB had confirmed the Israeli buildup along the Syrian border.

Nasser was in a difficult position. He had received humiliating rebukes for Egypt's lack of action after the recent Israeli attacks on Jordan and Syria. This, combined with perceived Israeli threats to topple the Syrian regime and calls from the Soviets to honor the Syrian-Egyptian defense agreement, left Nasser feeling as though he had no option other than to display solidarity with Syria. Another factor affecting Nasser’s calculation was the ongoing Egyptian involvement in the civil war in Yemen. Egypt had 130,000 troops in Yemen since 1962, and in 1967, there was still no end in sight for Egyptian involvement it that conflict.

On May 14, Nasser began the re-militarization of the Sinai, concentrating large numbers of tanks and troops there. This move was reminiscent of what he had done in the Rotem Crisis, although this time it was done openly. Field Marshal Amer explained to Pozhidaev, that the influx of troops into Sinai was a deterrent for Israel. He said: "Israel will not risk starting major military actions against Syria, because if it does Egyptian military units, having occupied forward initial positions on this border will immediately move out on the basis of the mutual defense agreement with Syria.” On May 16, Ahmed el-Feki, Egypt's Under Secretary of State, assured David Nes, US chargé d'affaires in Cairo that Egypt would not take the initiative in attacking Israel, but would only come to their aid in case of a large-scale Israeli attack against Syria. Nes came away from the conversation "certain" that Egypt had "no aggressive intent.” However, in late May, Field Marshal Amer had formulated a plan for initiating an attack on Israel. The plan was code-named Operation Dawn, and called for the strategic bombing of Israeli airfields, ports, cities, and the Negev Nuclear Research Center. Arab armies would then invade Israel, and cut it in half with an armored thrust through the Negev. Amer told one of his generals that "This time, we will be the ones to start the war."

At 10:00 p.m. on May 16, 1967, General Fawzi handed a letter from Nasser to the commander of the United Nations Emergency Force, in Sinai, General Indar Rikhye. It read in part: “For your information, I gave my instructions to all UAR armed forces to be ready for action against Israel, the moment it might carry out any aggressive action against any Arab country. Due to these instructions our troops are already concentrated in Sinai on our eastern border. For the sake of complete security of all UN troops which have installed observation posts along our borders, I request that you issue orders to withdraw all these troops immediately." Rikhye said he would ask the Secretary-General for instructions.

Detailed archival studies revealed that the original letter had not demanded a full withdrawal of UNEF, but ordered that they vacate the Sinai and redeploy in Gaza. However, UN Secretary General U Thant demanded an all-or-nothing clarification from Nasser, leaving the Egyptians with little choice but to ask for their total withdrawal. U Thant then attempted to negotiate with Nasser about the fate of UNEF, but on May 18 the Egyptian Foreign Minister, Mahmoud Fawzi (No relation to General Mohamed Fawzi) informed all the nations composing UNEF, that the UNEF mission in Egypt and the Gaza Strip had been terminated and that they must leave immediately. The Governments of India and Yugoslavia decided to withdraw their troops from UNEF, regardless of the decision of U Thant. While this was taking place, U Thant suggested that UNEF be redeployed to the Israeli side of the border, but Israel refused, arguing that UNEF contingents from countries hostile to Israel would be more likely to impede an Israeli response to Egyptian aggression than to stop that aggression in the first place. General Rikhye was given the order to begin withdrawal on May 19. The withdrawal of UNEF was to be spaced over a period of some weeks. The troops were to be withdrawn by air and by sea from Port Said. The withdrawal plan envisaged that the last personnel of UNEF would leave the area on June 30, 1967. On the morning of May 27, Egypt demanded that the Canadian contingent be evacuated within 48 hours "on grounds of the attitude adopted by the Government of Canada in connection with UNEF and the United Arab Republic Government's request for its withdrawal, and to prevent any probable reaction from the people of the United Arab Republic against the Canadian Forces in UNEF." The withdrawal of the Canadian contingent was accelerated and completed on May 31, with the effect that UNEF was left without its logistics and air support components.

Before UNEF was deployed in 1956, negotiations were necessary with Egypt. A key principle governing the stationing and functioning of UNEF, and of all later peacekeeping forces worldwide, was the consent of the host government. Since it was not an enforcement action under Chapter VII of the Charter, UNEF could only enter and operate in Egypt with the consent of the Egyptian Government. This principle was clearly stated by the General Assembly in the language of Resolution 1001. The resolution provided the authority to guarantee the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Sinai and their replacement with UNEF. However, the entry of UNEF into Egyptian territory could only come with Egypt’s consent, and UNEF’s presence could only last as long as that consent was maintained. Since Israel refused to accept UNEF on its territory, the force could only be deployed on the Egyptian side of the border, and thus its functioning was entirely contingent upon the consent of Egypt as the host country. Once that consent was withdrawn, its operation could no longer be maintained.

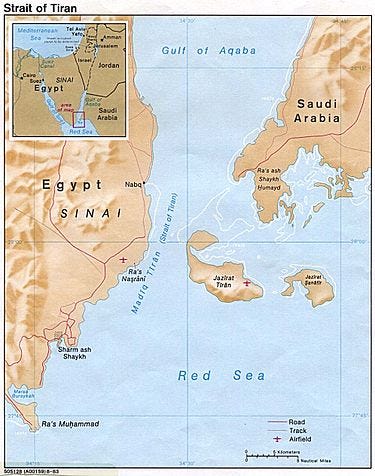

In the lead-up to June 1967, Israeli Prime Minister Eshkol had repeated declarations that Israel had made in 1957, saying that closure of the Straits of Tiran would be an act of war. 90% of Israeli oil passed through the Straits of Tiran and it was their only link for trade with the Eastern world. Then, on May 22, Egypt announced that the Straits of Tiran would be closed to "all ships flying Israeli flags or carrying strategic materials starting May 23”. In order to enforce the blockade, Egypt falsely announced that the Tiran straits had been mined and oil tankers that were due to pass through the straits were delayed. According to Sami Sharaf, Minister of State for Presidential Affairs, Nasser knew that the decision to block the Tiran straits made the war "inevitable". Nasser stated, "Under no circumstances can we permit the Israeli flag to pass through the Gulf of Aqaba." The closure of the Tiran Straits was closely linked to the previous withdrawal of the UN peacekeepers, because having the peacekeepers (rather than the Egyptian military) at Sharm el-Sheikh was important for keeping that waterway open. Nasser himself said that the closure of Tiran was necessary once Egyptian troops occupied Sharm el-Sheikh, because “no self-respecting Egyptian would be able to overlook an Israeli ship passing through the straits”.

On May 25 1967, Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban landed in Washington "with instructions to discuss American plans to re-open the Straits of Tiran". As soon as he arrived, he was given new instructions in a cable from the Israeli government. The cable said that Israel had learned of an imminent Egyptian attack, which overshadowed the blockade. No longer was he to emphasize the Straits issue. He was instructed to ‘inform the highest authorities, of this new threat and to request an official statement from the United States that an attack on Israel would be viewed as an attack on the United States." Eban was livid, he was unconvinced that Nasser was either determined or even able to attack, and saw these instructions as inflating the Egyptian threat, and flaunting the Israeli’s weakness, in order to extract a pledge that the President could never make. He later described the cable as an "...act of momentous irresponsibility, which lacked wisdom, veracity and tactical understanding," and came to the conclusion that the genesis of the cable was Chief of the General Staff Yitzchak Rabin's indecisive state of mind.

Despite his own skepticism, Eban followed his instructions during his first meeting with Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Under Secretary Eugene Rostow, and Assistant Secretary Lucius Battle. American intelligence experts spent the night analyzing the Israeli claims and on May 26, Eban met with Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and eventually President Lyndon B. Johnson. In a memo to the President, Rusk rejected the claim of an Egyptian and Syrian attack being imminent, stating "our intelligence does not confirm the Israeli estimate”. According to declassified documents from the Johnson Presidential Library, President Johnson and other top officials in the administration did not believe war between Israel and its neighbors was necessary or inevitable. During a visit to the White House on May 26, President Johnson told Eban “All of our intelligence people are unanimous that if the UAR attacks, you will whip the hell out of them.” Therefore, Johnson declined to airlift special military supplies to Israel or even to publicly support it and Eban left the White House distraught. After some more time to think, Johnson and his advisors thought, ‘What if their intelligence sources are better than ours?’ Johnson decided to fire off a Hotline (A direct line to Moscow serviced by teletype, set up after the Cuba Missile Crisis in 1962) message to the Premier of the Soviet Union, Alexei Kosygin, in which he said, "We've heard from the Israelis, but we can't corroborate it, that your proxies in the Middle East, the Egyptians, plan to launch an attack against Israel in the next 48 hours. If you don't want to start a global crisis, prevent them from doing that." As a result of that message, at 2:30 a.m. on May 27, Soviet Ambassador to Egypt Dimitri Pojidaev woke up Nasser and read him a personal letter from Kosygin in which he said, "We don't want Egypt to be blamed for starting a war in the Middle East. If you launch that attack, we cannot support you." Nasser knew that operation Dawn was set to be launched in just a few hours, at sunrise. His mood soured when he realized that Israel had accessed Egyptian secrets and compromised them. Nasser hurried to an emergency meeting at headquarters, and told Amer about the exposure of Dawn and asked him to cancel the planned attack. Amer consulted his sources in the Kremlin, and they corroborated the substance of Kosygin's message. Despondent, Amer told the commander of Egypt's air force, Major General Mahmud Sidqi, that the operation was cancelled. The cancellation orders arrived to the pilots when they were already in their planes, awaiting the final go ahead.

Meanwhile, the Israeli government asked the US and UK to reopen the Straits of Tiran, as they had guaranteed they would in 1957. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson proposed an international maritime flotilla, made up of mostly merchant vessels, to assert an international right to navigation through the straits and quell the crisis. The plan was adopted by President Johnson, but received little support, with only Britain and the Netherlands offering to contribute ships. The British cabinet later stated that there was a new balance of power in the Middle East, led by the United Arab Republic, that was A) to the detriment of Israel and the Western powers and B) something Israel was going to have to learn to live with. On May 22, Chief of the General Staff, General Yitzhak Rabin reported to Israel's cabinet that the Egyptian forces were in a defensive posture and were not being deployed to attack. The cabinet was deadlocked over the issues of the blockade and Egyptian intentions in Sinai. Interior Minister Haim-Moshe Shapira, in particular pointed out that the Straits had been closed from 1951 to 1956 without the situation endangering Israel's security and Abba Eban said that Israel would have to move at America’s pace if they did not want to lose the support of the US. Eventually, after spirited discussion, the cabinet decided to attack Egypt if the Straits of Tiran were not re-opened by May 25. On May 24 Prime Minister Eshkol told his generals: "Nobody ever said we were an army for preventive war. I do not accept the mere fact that because the Egyptian army is deployed in Sinai makes a war inevitable. You did not receive all these weapons in order for you to say that now we are ready and well-equipped to destroy the Egyptian army, so we must do it”. Following an appeal from Under Secretary of State Eugene Rostow to allow time for negotiations to proceed. Israel agreed to a delay of ten days to two weeks. The generals were furious when the cabinet agreed to postpone the attack. For them it was about much more than the Straits of Tiran. What mattered was the big picture, Nasser was moving massive amounts of troops into the Sinai and uniting the entire Arab world against them, both of which were, in their view, a direct threat to Israel. On May 26, US intelligence informed Israel that it was their assessment that Egypt would not launch a preemptive attack on Israel, but only attack in response to an Israeli invasion of Syria. In a speech to Arab trade unionists on May 26, Nasser announced: "If Israel embarks on an aggression against Syria or Egypt, the battle against Israel will be a general one and not confined to one spot on the Syrian or Egyptian borders. The battle will be a general one and our basic objective will be to destroy Israel.” Nasser publicly denied that Egypt would strike first and spoke of a negotiated peace if Israel allowed all Palestinian refugees the right of return and of a possible compromise over the Straits of Tiran.

During May and June the Israeli government had worked hard to keep Jordan out of any war, making numerous calls for Jordan to refrain from hostilities. Israel was concerned about being attacked on multiple fronts, and did not want to have to deal with the West Bank. Jordan’s position there put them only eleven miles from Israel's coast. A well-coordinated attack would cut the country in half in less than two hours. Additionally, King Hussein had doubled the size of Jordan's army in the last decade and had US training and arms delivered as recently as early 1967. It was also feared that Jordan could be used as a staging point for operations against Israel. Therefore, an attack from the West Bank was always viewed by the Israeli leadership as a threat to Israel's existence. King Hussein was also caught in a no-win situation. If he allowed Jordan to be dragged into a war with Israel, they would face the brunt of an Israeli response, but if he remained neutral, he would be facing a full-scale insurrection among his own people.

In fact Army Commander-in-Chief General Sharif Zaid Ben Shaker warned in press conference that "If Jordan does not join the war, a civil war will erupt in Jordan.” On May 30, King Hussein flew to Cairo and signed a mutual defense treaty with Egypt, a treaty that placed all the Jordanian military under the command of an Egyptian general. When he returned to Amman deliriously happy crowds tried to lift up his Mercedes and carry it back to the palace. Hussein was not deluded. The crowds loved him because Nasser had accepted him, not the other way around. The move surprised foreign observers, because President Nasser had generally been at odds with Hussein, calling him an "imperialist lackey" just days earlier. Nasser said that any differences between him and Hussein were erased "in one moment" and declared: "Our basic objective will be the destruction of Israel. The Arab people want to fight." At the end of May, 1967, Jordanian forces were placed under the command of Egyptian general Abdul Munim Riad. On the same day, Nasser proclaimed: "The armies of Egypt, Jordan and Syria are poised on the borders of Israel to face the challenge, while standing behind us are the armies of Iraq, Algeria, Kuwait, Sudan and the whole Arab nation. This act will astound the world. Today they will know that the Arabs are arranged for battle, the critical hour has arrived. We have reached the stage of serious action and not of more declarations." Also on May 30, the US Ambassador to Egypt, Richard Nolte reported that Nasser "cannot and will not retreat" and "he would probably welcome, but not seek, a military showdown with Israel.” The President of Iraq, Abdul Rahman Arif, said that "the existence of Israel is an error which must be rectified. This is an opportunity to wipe out the ignominy which has been with us since 1948.” And predicted that "there will be practically no Jewish survivors". Syria’s Defense Minister Hafez al-Assad declared: "Our forces are now entirely ready, not only to repulse the aggression, but to initiate the act of liberation itself, and to explode the Zionist presence in the Arab homeland. The Syrian Army, with its finger on the trigger, is united. I, as a military man, believe that the time has come to enter into a battle of annihilation. On June 3, days before the war, Egypt sent two battalions of commandos to Amman, tasked with infiltrating Israel's borders and engaging in attacks and bombings, to draw the IDF into attacking Jordan and ease the pressure on the Egyptians. Soviet-made artillery and Egyptian military supplies and crews were also flown to Jordan. At the same time several other Arab states not bordering Israel, including Iraq, Sudan, Kuwait and Algeria, began mobilizing their armed forces.

Spurred by the virulent Arab rhetoric and bloody threats pouring out of Arab radio stations, a doom-laden mood overcame the country. People made black jokes: "Let's meet after the war. Where? In a phone box," alluding to how many Israelis might be left. 1967 was only 22 years after the end of the Holocaust, it was not surprising that the Arab propaganda hit home. The sense of the Israeli public was of a heightened fear of another holocaust on the horizon. The government stockpiled coffins; rabbis consecrated parks as emergency cemeteries and tens of thousands of pints of blood were donated.

A few days earlier Meir Amit, the head of the Mossad, had travelled to Washington DC on a false passport, in disguise and had a crucial meeting with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Amit was deeply concerned about the mobilization of nearly the entire male population under the age of 50 and its effect on the economy of Israel. Amit told McNamara that he was going to recommend a war. McNamara asked only two questions. “How long and how many casualties?”. Amit answered it would take a week and cause less casualties than the War of Independence, around 6,000. McNamara said 'I read you loud and clear'." With that, the Americans had given a clear signal. They had been told that Israel would be going to war and had made no attempt to stop it happening. Amit travelled back to Israel with the US Ambassador to Israel, Abe Harman, on an aircraft full of gas masks. They arrived in Tel Aviv on the evening of Saturday June 3.

A car took them straight to Prime Minister Eshkol's apartment, where he was waiting with his key ministers. Amit recommended an immediate attack. Harman wanted them to wait another week or so. The newly appointed Minister of Defense Moshe Dayan disagreed: "If we wait for seven to nine days, there will be thousands dead. It's not logical to wait. Let's strike first and then look after the political side." Everyone who was there had no doubt that the decision had been taken. Israel was going to war. The cabinet ratified it the next morning.

We are now on the eve of the war that would change both the map and the history of the Middle East. In my next post I will cover the actual war and it’s aftermath. I hope you are enjoying this series and look forward to reading them as they come out. Please click below to leave a comment and let me know how I’m doing.

If this had pages I’d call it a page turner - so it’s a page scroller, I guess. Really well done!!

Excellent report leading up to the war. I was 15 during the summer of 1967. My family was camping with my favorite aunt and uncle when the war broke out. I vaguely recall the adults discussing it but not knowing much about the history of the area . Since then I have grown up and spent 38 years in the Navy and Navy Reserve. I was recalled to active duty during Desert Storm in 1990-91. Needless to say I have learned much about the Arabs and the Jews since 1967.