In A Short History of Israel Part VII, click below to read it. I described the situation

leading up to the Suez Crisis, where British, French and Israeli forces attempted to capture the Suez canal after it had been nationalized by Egyptian President Gamel Abdel Nasser. Today I will finish this strange but important moment of history. A moment that elevated a leader to nearly god-like status, brought down another one and set the stage for one of the most lopsided defeats in history.

One more thing I just found in the build-up to the Suez Crisis. It is too sad not to include although it doesn’t necessarily fit here. Roi Rotberg was born in Tel Aviv in 1935. He served as a messenger boy for the IDF in the War for Independence and eventually joined the IDF and after completing an officer's course, he settled in Nahal Oz as the Security Officer. As Security Officer he was regularly involved in chasing off infiltrators, sometimes using lethal force. He married Amira Glickson and had a son, Boaz, who was an infant at the time of his death. On April 29 1956 he saw Arab workers begin to harvest wheat in the kibbutz’s fields. He rode towards them on horseback to chase them off. Unfortunately, the Arabs had prepared an ambush for Rotberg. As he approached, others emerged from hiding to attack. He was shot off his horse, beaten and shot again, then his body was dragged into Gaza. Badly mutilated, his body was returned on the same day after United Nations intervention.

The next day IDF Chief of the General Staff Moshe Dayan traveled to Nahal Oz to personally give the eulogy. This speech is remembered in Israel like the Gettysburg Address is in America. This is what Dayan said:

"Early yesterday morning Roi was murdered. The quiet of the spring morning dazzled him and he did not see those waiting in ambush for him, at the edge of the furrow. Let us not cast the blame on the murderers today. Why should we declare their burning hatred for us? For eight years they have been sitting in the refugee camps in Gaza, and before their eyes we have been transforming the lands and the villages, where they and their fathers dwelt, into our estate. It is not among the Arabs in Gaza, but in our own midst that we must seek Roi's blood. How did we shut our eyes and refuse to look squarely at our fate, and see, in all its brutality, the destiny of our generation? Have we forgotten that this group of young people dwelling at Nahal Oz is bearing the heavy gates of Gaza on its shoulders? Beyond the furrow of the border, a sea of hatred and desire for revenge is swelling, awaiting the day when serenity will dull our path, for the day when we will heed the ambassadors of malevolent hypocrisy who call upon us to lay down our arms. Roi's blood is crying out to us and only to us from his torn body. Although we have sworn a thousandfold that our blood shall not flow in vain, yesterday again we were tempted, we listened, we believed.

We will make our reckoning with ourselves today; we are a generation that settles the land and without the steel helmet and the cannon's maw, we will not be able to plant a tree and build a home. Let us not be deterred from seeing the loathing that is inflaming and filling the lives of the hundreds of thousands of Arabs who live around us. Let us not avert our eyes lest our arms weaken. This is the fate of our generation. This is our life's choice - to be prepared and armed, strong and determined, lest the sword be stricken from our fist and our lives cut down. The young Roi who left Tel Aviv to build his home at the gates of Gaza to be a wall for us was blinded by the light in his heart and he did not see the flash of the sword. The yearning for peace deafened his ears and he did not hear the voice of murder waiting in ambush. The gates of Gaza weighed too heavily on his shoulders and overcame him."

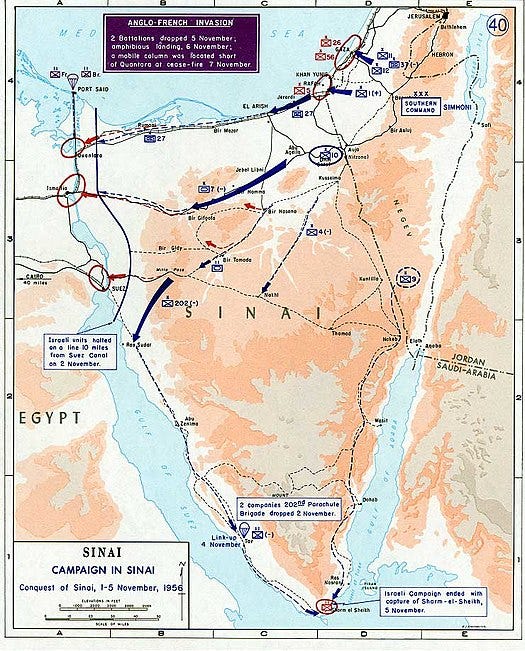

At 3:00 pm on October 29 1956, Operation Kadesh began with Israeli Air Force P-51 Mustangs launching a series of attacks on Egyptian positions all over the Sinai.

A battalion of paratroopers, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Rafael Eitan, was dropped into the Sinai east of the Suez Canal near the Mitla Pass, to secure the pass at Jabel Heitsn. The rest of the brigade, under the command of Colonel Ariel Sharon linked up with Eitan and consolidated their position. As the paratroopers were being dropped into the Sinai, the 9th Infantry Brigade captured Ras al-Naqbin in a night attack. Ras al-Naqbin would become the staging point for the upcoming assault on Sharm el-Sheikh. The 4th Infantry Brigade, under the command of Colonel Josef Harpaz, captured another important staging point, al-Qusaymah, which would be used as a jumping off point for the assault against Abu Uwayulah.

Egyptian commander, Field Marshal Abdel Amer treated the reports of an Israeli incursion into the Sinai as a large raid instead of an invasion, and he did not order a general alert. By the time that Amer realized his mistake, the Israelis had made significant advances into the Sinai.

The village of Abu Uwayulah, 16 miles inside Egyptian territory, served as the crossroads for the entire Sinai, and was a key Israeli target. To the east of Abu Uwayulah were several ridges that formed a natural defensive zone known to the Israelis as the "Hedgehog”, it could only be assaulted from the east flank of Umm Qataf ridge and the west flank of Ruafa ridge. Holding the Hedgehog, in a series of well-fortified trenches, were 3,000 Egyptians of the 3rd Infantry Division commanded by Colonel Sami Yassa. On October 30, a probing attack by Israeli armor under Major Izhak Ben-Ari became a general assault on the Umm Qataf ridge. The attack was repulsed with heavy causalities on both sided. During the fighting, Colonel Yassa was badly wounded and replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Saadedden Mutawally. To the south, another unit of the Israeli 7th Armored Brigade, discovered a gap in the Jebel Halal ridge of the Hedgehog and took it. Colonel Mutawally failed to appreciate the extent of the danger posed to his forces and to Abu Uwayulah, by the IDF breakthrough at al-Dayyiqa.

On October 30, the Security Council held a meeting, at the request of the United States, where a draft resolution calling upon Israel to immediately withdraw its armed forces behind the established armistice lines, was submitted. A similar draft resolution sponsored by the Soviet Union was also rejected.

At dawn on October 31, led by Colonel Avraham Adan, the 7th Brigade passed through the gap at al-Dayyiqa and attacked Abu Uwayulah. After an hour's fighting, Abu Uwayulah fell to the IDF. At the same time, the 10th Brigade launched an attack against the Ruafa ridge but the attack went nowhere and was ultimately unsuccessful.

On October 31, after a morning of punishing airstrikes on Egyptian positions, Adan committed all of his forces against the Ruafa ridge of the Hedgehog, in a three-pronged attack with one armored force attacking the northeastern edge of Ruafa, mechanized infantry attacking the northern edge of the ridge and a feint attack from a neighboring knoll. During the chaotic battle, with combat devolving into hand-to-hand fighting, every IDF tank involved in the effort was destroyed, and both sides were stretched to the brink. As the sun rose on November 1, it was the IDF that was in control of Ruafa ridge. Another IDF assault that night, this time by the 10th Infantry Brigade on Umm Qataf was less successful with much of the attacking force getting lost in the darkness, resulting in a series of confused attacks that ended in failure. Moshe Dayan, who had grown impatient with the failure to storm the Hedgehog, fired the 10th Brigade's commander Colonel Shmuel Golinda and replaced him with Colonel Israel Tal. On the morning of November 1, after massive Israeli and French napalm attacks at Umm Qataf, Colonel Tal and the 10th Brigade, along with the 37th Armored Brigade assaulted Umm Qataf, and once again, were turned back. However, the ferocity of the IDF assault combined with rapidly dwindling stocks of water and ammunition caused Colonel Mutawally to order a general retreat from the Hedgehog.

The Sinai was not the only focus of Israeli forces, the IDF were also engaged in operations in the Gaza Strip. The city of Rafah was strategically important to Israel because control of that city would sever the Gaza Strip from the Sinai Peninsula and secure a road to the two main cities of the Northern Sinai, al-Arish and al-Qantarah. Occupying the forts outside of Rafah were a mixture of Egyptian and “Palestinian” forces of the 5th Infantry Brigade commanded by Brigadier General Jaafar al-Abd. The 87th Palestinian Infantry Brigade occupied Rafah itself. To the south of Rafah were a series of mine-filled sand dunes and to the north were a series of fortified hills. The IDF force tasked with capturing the city, was composed of the 1st Infantry Brigade led by Colonel Benjamin Givli and 27th Armored Brigade commanded by Colonel Haim Bar-Lev.

On October 31, Givli and Bar-Lev were ordered to seize Crossroads #12 in the central Rafah area, and to focus on breaking through Egyptian lines rather than reducing every strongpoint. The IDF assault began with Israeli sappers and engineers clearing a path through the minefields that surrounded Rafah. French warships led by the cruiser George Leygues, provided fire support. Using the two paths cleared through the minefields, IDF tanks entered the Rafah salient, and under heavy Egyptian artillery fire, raced ahead and took the vital junction. In the north, the Israeli troops fought a confused series of night actions, but were successful in securing six hills outside Rafah. At that point, with the tactical situation deteriorating, General al-Abd ordered his forces to abandon their posts outside of Rafah and retreat into the city. With Rafah more or less cut off and Israeli forces controlling the northern and eastern roads leading into the city, Dayan ordered the AMX-13s of the 27th

Armored Brigade to strike west and take al-Arish. After the encirclement of Rafah, Field Marshal Amer ordered his forces to fall back towards the Suez Canal. On November 1, General al-Abd and his remaining forces slipped through a gap in the Israeli lines and started their retreat to Suez, three hours later Givli and his men entered Rafah, while Bar-Lev continued the thrust across Northern Sinai.

On October 30, as planned, France and the United Kingdom issued a demand for Egypt and Israel to end the fighting, and withdraw two miles from each other’s lines. As the announcement was made, a demand that they knew would be rejected by both countries, France and the UK were activating forces that had already be built-up in the region. To support the “intervention” (read invasion), Britain and France had deployed a large contingent of air forces to Cyprus and Malta. The two airbases on Cyprus were so congested that a third field, one in dubious condition, had to be brought into use for French aircraft. The British aircraft carriers HMS Eagle, HMS Albion, HMS Bulwark, HMS Ocean and HMS Theseus, as well as the French battleship Jean Bart and carriers Arromanches and La Fayette and a large escort force were on station in the Eastern Mediterranean. The Theseus and Ocean were to act as helicopter carriers for the world’s first helicopter-borne assault.

With the Egyptian forces in retreat, Bar-Lev’s brigade met little resistance in their advance. Not until the Jeradi Pass in the northern Sinai did the IDF run into serious opposition, but a series of hook attacks, combined with airstrikes, out-flanked the Egyptian positions, leading to an Egyptian defeat at the Jeradi Pass. On November 2, Bar-Lev's forces took al-Arish. Although the city itself fell without a fight, Bar-Lev's troops were occasionally under fire from Egyptian stragglers and Moshe Dayan's radio operator was killed in one such incident.

Meanwhile, the IDF attacked the Egyptian defenses outside of Gaza City, late on November 1. After breaking through the Egyptian lines, the Israeli tanks and their accompanying infantry attacked the al-Muntar fortress, killing or capturing 3,500 Egyptian National Guard troops. By noon on the 2nd, Gaza City was secure and the force moved to attack Khan Yunis. After a fierce battle,

M-50 Super Sherman tanks from the Israeli 37th Armored Brigade, broke through the heavily fortified lines outside of Khan Yunis and after some street-fighting, the city fell to the Israelis. By noon on November 3, the Israelis had control of almost the entire Gaza Strip save for a few isolated strong points, which were soon attacked and taken.

Sharm el-Sheikh was the last Israeli objective but there weren't any good roads linking the boarder town of Ras an-Naqb, which had been taken on the first day of the war, to Sharm el-Sheikh. Moshe Dayan assigned the attack on Sharm el-Sheikh to the 9th Brigade under the command of Abraham Yoffe. However, because of fears of Egyptian air attack while crossing the open desert, Yoffe was ordered to wait until air superiority had been established over Sinai.

In the meantime, Israeli paratroopers were dropped to the west and took the town of Tor, in an effort to outflank Sharm el-Sheikh. On November 2, the IAF had control of the air over the entire peninsula after inflicting heavy loses, causing Amer to withdraw all his remaining air forces to southern Egypt. In the evening of the 2nd, Yoffe and his brigade started moving towards Sharm el-Sheikh with air cover and Israeli Navy vessels in support. The Egyptian forces at Sharm el-Sheikh had the advantage of holding one of the most strongly fortified positions in the entire Sinai. However they had been subjected to heavy Israeli air attacks from the beginning of the war. After numerous skirmishes on the outskirts of Sharm el-Sheikh, Yoffe ordered an attack on the port around midnight on November 4. After four hours of heavy fighting, Yoffe ordered his men to retreat. A few hours later after a massive artillery barrage and airstrikes, including napalm attacks, Yoffe renewed the attack. At 9:30 am on November 5, the Egyptian commander, Colonel Raouf Mahfouz Zaki, surrendered Sharm el-Sheikh.

On October 31, Operation Musketeer began with an intensive bombing campaign. The Cyprus and Malta based bombers took off, to destroy Cairo Airport, only to be ordered back by Eden himself, when he learned that American civilians were being evacuated from there. Fearful of backlash if American civilians were killed by British bombing, Eden sent half the force home and the other half to attack Almaza Airbase outside of Cairo. Starting at dawn on November 1, carrier-based aircraft began a series of daytime strikes on targets all over Egypt. By nightfall, the Egyptian Air Force had lost 200 planes. After the destruction of the Egyptian Air Force, General Stockwell, ordered the beginning of Phase II, a wide-ranging interdiction campaign, beginning on November 3.

De Havilland Sea Venoms of the RAF and French F-84 Thunderstreaks from Cyprus pounded the canal zone airfields. Royal Navy Hawker Sea Hawks and Sea Venoms attacked three airfields in the Cairo area. The antiaircraft fire was light, and all the attackers returned. By early afternoon, the carriers were 50 miles offshore and launching a fresh sortie every few minutes.

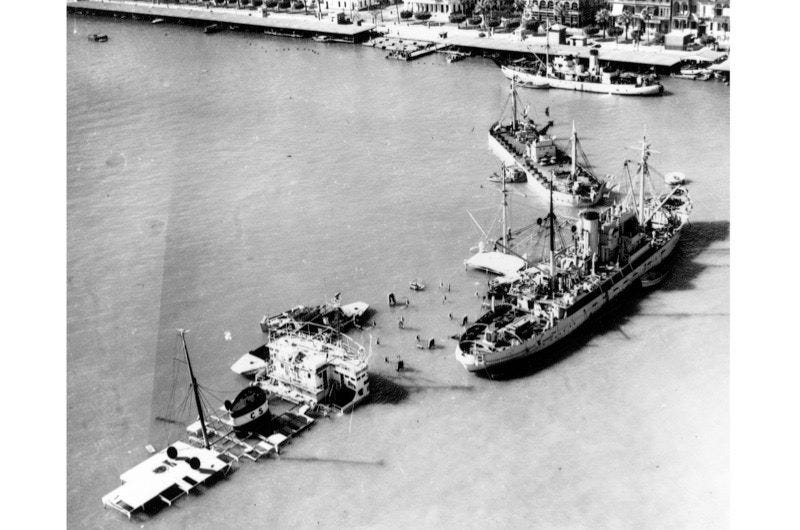

On Cyprus, planes were taking off or landing at the rate of one a minute. The jets were joined by propeller-driven Vought F4U Corsairs from the French carriers. Corsairs sank an Egyptian torpedo boat and damaged a destroyer off Alexandria. The vessel Akka was attacked by Sea Hawks as it was being towed into the main channel of the canal. The 347-foot-long ship, filled with cement and debris, was the first of numerous vessels scuttled to cause the canal’s first major blockage in its 87-year history.

British bombs also dropped the Firdan Bridge into the shipping lane. Nasser responded by sinking all 40 ships present in the canal closing it to all shipping. It would not be open to shipping until early 1957. Consequently, Nasser and the British themselves, had deprived France, the UK and Israel of their stated purpose, of keeping the waterway open.

Despite the risk of an invasion in the canal zone, Field Marshal Amer ordered Egyptian troops in the Sinai to stay put. Amer confidently assured Nasser that the Egyptians could defeat the Israelis in the Sinai and then defeat the Anglo-French forces once they came ashore in the canal zone. The joint British/French force was originally to land at Alexandria, but the location was later switched to Port Said, since a landing at Alexandria would have faced major opposition, necessitating the landing of an entire armored division. Also, the preliminary bombardment of Alexandria would have caused thousands of civilian casualties. Even after the relocation, the naval bombardment of Port Said was less than effective because of the decision to only use 105mm guns instead of the larger 380mm or 203mm guns, in an effort to minimize civilian casualties.

Later on the 31st, after considering the grave situation in Egypt and the lack of consensus among the permanent members of the Security Council, the Council passed Resolution 119, calling for an emergency special session of the General Assembly in order to make recommendations to end the fighting. The emergency special session was convened November 1. After hours of debate, early on November 2, the General Assembly adopted Resolution 997. The vote was 64 in favor and 5 opposed (Australia, New Zealand, Britain, France, and Israel) with 6 abstentions. It called for an immediate ceasefire, the withdrawal of all forces behind the 1948 Armistice lines, an arms embargo on Israel, and the reopening of the Suez Canal. The Secretary-General was requested to observe and report on compliance to both the Security Council and General Assembly, for further action as deemed appropriate.

Regardless of any UN action, Operation Telescope began in the early morning of November 5. When an advance element of the 3rd Battalion of the 3rd Parachute Regiment (3 Para) were dropped onto El Gamil Airfield.

Once the paratroopers landed, their Sten guns, three-inch mortars and anti-tank weapons had great effect. Having taken the airfield, the remainder of the battalion flew in by helicopter and secured the area around the airfield. Troops were also dropped onto Port Faud to secure the airfield, preventing Egyptians forces from mounting a defense against further airdrops. The lightly armed paratroopers were quickly able to push the Egyptians back, who withdrew to favorable terrain to avoid annihilation at the hands of the superior British forces. With close support from carrier-based Hawker Sea Hawks and Westland Wyverns, the British paratroopers took Port Said's sewage works. 3 Para then moved onto Port Said and called in airstrikes against the highly defended Coast Guard Barracks, but even after the attacks from RAF planes, that inflicted heave casualties, 3 Para could not breakthrough the barracks and retreated to the newly occupied, sewage works.

10 miles to the east, Lieutenant Colonel Pierre Chateau-Jobert and elements of the 2nd Colonial Parachute Regiment (2 RPC) are dropped over Rawsa. The 500 paratroopers, hastily redeployed from combat in Algeria, secured the al-Raswa bridges and the Said waterworks, an important objective to control in a desert city. Close-air-support missions hit two large oil storage tanks in Port Said, which went up in flames and covered most of the city in a thick cloud of smoke for the next several days. With supplies cut off to Port Said, and a potential chokepoint captured by mid-morning, the French had achieved all their objectives on the first day.

At this point the Egyptian commander at Port Said, General Salahedin Moguy proposes a truce. In the ensuing meeting with Generals Butler, Chateau-Jobert and Massu. Moguy was offered the terms of surrendering the city and marching his men to the Gamil airfield to be taken off to prisoner-of-war camps in Cyprus. However, the Moguy proposed truce had only been made to buy time for his men to dig in. When fighting began again, vans with loudspeakers travelled through the city announcing that London and Paris had been bombed by the Russians and that World War III had started. The paratroopers alone were not enough to capture the city and British and French naval commanders urged that the sea-borne landings start the next day.

At first light on November 6, Royal Marines of 40 and 42 Commandos stormed the beaches, using World War II vintage landing craft. The battle group standing offshore gave covering fire causing considerable damage to the Egyptian batteries and gun emplacements.

Port Said sustained considerable damage and was set ablaze. 42 Commando tried to bypass Egyptian positions as much as possible to avoid being bogged down. The Royal Marines of 40 Commando had the advantage of being supported by Centurion tanks as they landed on their assigned beach but upon entering downtown Port Said, the Marines became engaged in fierce urban combat as the Egyptians used the Casino Palace Hotel and other strong points as fortresses. At the same time elements of the 16th Parachute Brigade led by Brigadier General M.A.H. Butler and a contingent of the Royal Tank Regiment set off south along the canal bank on November 6 to capture Ismailia.

Nasser proclaimed the Suez War to be a "people's war”. Egyptian troops were ordered to don civilian clothes and weapons were freely handed out to civilians. From Nasser's point of view, this set of conditions, presented the British and French with an unsolvable dilemma. If the Allies reacted aggressively to the "people's war", then that would result in the deaths of innocent civilians and bring world sympathy to his cause while weakening morale in Britain and France. If the Allies reacted cautiously to the "people's war", that would in result in Allied forces becoming bogged down by snipers and small unit attacks, forces who had the advantage of attacking with near impunity by hiding among crowds of apparent non-combatants. These tactics worked especially well against the British. British leaders, especially Prime Minister Antony Eden and the First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Louis Mountbatten were afraid of being labelled "murderers and baby killers", and sincerely attempted to limit Egyptian civilian deaths. Eden frequently interfered with Musketeer bombing missions, cancelling targets he felt were likely to cause excessive civilian deaths, and restricting the gun sizes used in the Port Said landings. Despite the obvious paradox between Eden's concern for Egyptian civilians and the object of the Phase II bombing campaign, which was intended to terrorize the Egyptian people, British bombing still killed hundreds of Egyptian civilians during Musketeer II, even without a deliberate policy of "area bombing" such as that employed against Germany in World War II. At Port Said, the heavy fighting in the streets and the resulting fires destroyed much of the city, killing many civilians.

Also on the 6th, Marines of 45 Commando conducted the first large-scale helicopter landing of combat troops in history, but met stiff resistance, with Egyptian shore batteries shooting down several helicopters. The helicopter of 45 Commando commander Lieutenant Colonel Norman Tailyour landed in a stadium that was still under Egyptian control, resulting in a very hasty retreat. House to house fighting against well-entrenched Egyptians, caused further delays and casualties.

Most Egyptian soldiers now wore civilian clothing and operated in small groups. They were joined by thirteen small groups of civilians. As the British captured key positions, the Egyptians were gradually pushed back. Especially fierce fighting took place at Port Said's Customs House and Navy House. The Egyptians destroyed Port Said's Inner Harbor, which forced the British to use the Fishing Harbor to land their forces. While the British were landing at Port Said, the men of the 2 RPC at Raswa fought off Egyptian counter-attacks. The 2nd Battalion of 3 Para landed by ship in the harbor, accompanied by Centurion tanks of the 6th Royal Tank Regiment but by noon the Marines linked up with the French Paratroopers. The link-up of British and French forces occurred close to the offices of the Suez Canal Company. While the building was captured with ease, the surrounding warehouses were heavily defended and were only taken in fierce fighting with the help of point-blank fire from Centurion tanks. After establishing themselves in a position in downtown Port Said, 42 Commando headed down the Shari Muhammad Ali, the main north–south road to link up with the French forces at the Raswa bridge and the Inner Basin lock, taking Port Said's gasworks along the way Meanwhile, 40 Commando supported by the Royal Tank Regiment continued their effort to clear downtown Port Said of snipers. Because causalities were becoming an issue, Colonel Tailyour was forced to call for reinforcements that were brought in by another helicopter landing.

In the afternoon of November 6, 522 additional French paratroopers of the 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1 REP) were dropped near Port Faud with constant air support for Corsairs from the two French carriers. The paratroopers also had support from a small contingent of French AMX-13 light tanks. After securing Port Fuad, the French fought a pitched battle for an Egyptian police post a mile to the east of the town.

With nothing going as hoped at the UN and avenues for ending the crisis before it became a bigger issue, slipping by the wayside. The Eisenhower administration resorted to, what the UK would call, “less than scrupulous methods”. Baron Harold Caccia, the UK ambassador to the United States, was informed by Secretary of State John Forster Dulles, that if the UK did not call for an end to the hostilities, then the US would devalue the Pound Sterling, the British currency, sending Britain into a financial crisis. When they were informed of the US message, the cabinet was divided but Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden called a ceasefire, without notifying Israeli or French officials first.

After hearing rumors that General Moguy wished to surrender (again), both Stockwell and Beaufre left their command ship HMS Tyne for Port Said. After landing, they learned that once again the rumors were not true, but instead of returning to the Tyne, both Stockwell and Beaufre spent the day in Port Said. Late in the day they learned that the UK and France had accepted the UN brokered ceasefire and it was to come into effect in five hours' time. At 9:00 pm, in order to improve the Allied bargaining position, he ordered the 6th Royal Tank Regiment to race with all speed and take al-Qantarah. What followed was a confused series of melee actions down the road to al-Qantarah that ended, at 2:00 am when the ceasefire came into effect, and the British forces were at al-Cap, a village four miles north of al-Qantarah.

British casualties stood at 22 killed and 96 wounded, while French casualties were 10 killed and 33 wounded. Israeli losses were 172 killed and 817 wounded. Egyptian casualties against the Israelis, were 2,000 killed with 4,000 wounded, while losses to the Anglo-French operation were 650 killed and 900 wounded. 1,000 Egyptian civilians are estimated to have died. There are claims that after taking Khan Yunis, the IDF committed a massacre, known as the Khan Yunis Killings. Israel maintained that the Arabs were killed in the street-fighting. The Arabs, claimed that Israeli troops started executing unarmed people after the fall of Khan Yunis. On December 15, the claims, were reported to the UN General Assembly, by Henry Labouisse, the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), who reported from "trustworthy sources" that 275 people were killed in the massacre of which 140 were refugees and 135 local residents. In both Gaza City and Khan Yunis, street-fighting led to the deaths of dozens, perhaps hundreds of non-combatants. Food and medicine distribution for refugees in need of assistance was complicated when some Arabs looted the warehouses belonging to the UNRWA. The situation was compounded by the widespread view in Israel that the responsibility for the care of the “Palestinian” refugees rested with the UNRWA, which led the Israelis to be slow with providing aid. The UN estimated that in total 447 to 550 Arab civilians were killed by Israeli troops during the first weeks of Israeli occupation of the strip. The manner in which these people were killed is disputed.

Despite the Egyptian defeat, Nasser emerged as a hero in the Arab world. Although Egyptian forces fought with mediocre skill during the conflict, many Arabs saw Nasser as the conqueror of European colonialism and Zionism, simply because Britain, France and Israel left the Sinai and the northern Canal Zone. Even Nasser's speeches after 1956 only provided superficial explanations of Egypt's military collapse in Sinai, based on some extraordinary British strategy and simplistic children's tales about the Egyptian air force's prowess in 1956. All were linked to the myth of orderly withdrawal from Sinai. All this was necessary to construct yet another myth, inflating and magnifying the odd and scattered resistance at Port Said into a Stalingrad-like tenacious defense, Port Said became the spirit of Egyptian independence and dignity. During the Nasser era, the fighting at Port Said become a symbol of Egyptian victory, linked to the global anti-colonial struggle. British historian D. R. Thorpe wrote of Nasser’s post-Suez self-confidence. “The Six Day War in 1967 was when reality kicked in—a war that would never have taken place if the Suez crisis had had a different resolution. "Were bluffing and histrionics in the nature of Nasser? It was bluffing that led to the crushing of Egypt in 1967, because of the mass self-deception exercised by leaders and followers alike ever since the non-existent 'Stalingrad which was Port Said' in 1956."

The attack on Egypt also greatly offended many in the Islamic world. In Pakistan, 300,000 people showed up in a rally in Lahore to show solidarity with Egypt while in Karachi, a mob chanting anti-British slogans burned down the British High Commission office. The Syrian government blew up the Kirkuk-Banjyas pipeline that allowed Iraqi oil to reach tankers in the Mediterranean to punish Iraq for supporting the invasion, and to cut Britain off from one of its main oil suppliers. The King of Saudi Arabia also imposed a total oil embargo on Britain and France.

While the military operation itself had been completely successful, for Britain and France, political pressure from the United States obliged both governments to accept the ceasefire terms drawn up by the United Nations. The United States also led condemnations of the Anglo-French action at the UN, marking a sharp break in the “Special Relationship” between the United States and the United Kingdom. Along with the Suez crisis, the United States was also dealing with the near-simultaneous Soviet intervention in the Hungarian revolution. Vice-President Richard Nixon later explained: "We couldn't on one hand, complain about the Soviets intervening in Hungary and, on the other hand, approve of the British and the French picking that particular time to intervene against Nasser". Beyond that, it was Eisenhower's belief that if the United States were seen to acquiesce in the attack on Egypt, that the resulting backlash in the Arab world might push the Arabs over to the Soviet Union. The political and psychological impact of the crisis had a fundamental impact on British politics. There had been stormy and violent debates in the House of Commons, that almost degenerated into fist-fights after several Labor MPs compared Eden to Hitler. He was also accused of misleading Parliament, yet the Prime Minister insisted, "We are not at war with Egypt now. There has not been a declaration of war by us. We are in an armed conflict." Eden never recovered from the crisis and resigned from office on January 9 1957. He had been Prime Minister for less than two years when he resigned, and his unsuccessful handling of the Suez Crisis eclipsed the 30 years of successes he had achieved in the the Foreign Service. The Suez crisis, though a blow to British power in the Near East, did not mark its end. However, Eden's successor, Harold Macmillan, accelerated the process of decolonization and sought to restore Britain's special relationship with the United States. British influence continued in the Middle East, Britain intervened successfully in Jordan to put down riots that threatened the rule of King Hussein in 1958 and in 1961 deployed troops to Kuwait to successfully deter an Iraqi invasion (seems familiar), but Suez was a blow to British prestige from which the country never fully recovered. By 1971 Britain had evacuated and granted independence to all its colonies east of Suez, except Hong Kong.

Franco-American ties never recovered from the Suez crisis. There had already been strains in the relationship, triggered by what Paris considered a betrayal of the French war effort in Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The incident demonstrated the weakness of the NATO alliance, especially in its lack of planning and cooperation beyond the European stage. French PM Mollet believed Eden should have delayed calling the Cabinet together until November 7, taking the whole canal in the meantime, then veto with the French any UN resolution on sanctions. General Charles de Gaulle, past and future President of France believed that the events in Suez demonstrated to France that it could not rely on its allies; the British had initiated a ceasefire in the midst of the battle without consulting the French, while the Americans had opposed Paris politically. The Suez war had an immense impact on French domestic politics. Much of the French Army officer corps felt that they been "betrayed" by what they considered to be the spineless politicians in Paris when they were on the verge of victory just as they believed they had been "betrayed" in Vietnam in 1954, and accordingly become more determined to win the war in Algeria, even if it meant overthrowing the government to do so. The Suez crisis therefore, helped set the stage for the military disillusionment with the Fourth Republic, which was to lead to its collapse in 1958.

Israel escaped the political humiliation that befell Britain and France following their swift, forced withdrawal. In addition, its stubborn refusal to withdraw without guarantees, even in defiance of the United States and United Nations, ended all Western efforts, mainly American and British ones, to impose a political settlement in the Middle East without taking Israel's security needs into consideration. When Israel refused to withdraw its troops from the Gaza Strip and Sharm el-Sheikh, President Eisenhower declared, "We must not allow Europe to go flat on its back for the want of oil." He sought UN-backed efforts to impose economic sanctions on Israel until it fully withdrew from Egyptian territory. Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson and minority leader William Knowland objected to American pressure on Israel. Johnson told Secretary of State John Foster Dulles that he wanted him to oppose "with all his skill" any attempt to apply sanctions on Israel. Dulles rebuffed Johnson's request, and informed Eisenhower of the objections made by the Senate. Eisenhower was insistent on applying economic sanctions to the extent of cutting off private American assistance to Israel, estimated to be over $100 million a year. Ultimately, the Democrat controlled Senate would not cooperate with Eisenhower's position on Israel. Eisenhower finally told Congress he would take the issue to the American people, saying, "America has either one voice or none, and that voice is the voice of the President – whether everybody agrees with him or not”. The President spoke to the nation by radio and television where he outlined Israel's refusal to withdraw, explaining his belief that the UN had "no choice but to exert pressure upon Israel”, but the American people weren't concerned about punishing Israel and nothing important came from the addresses.

The Israel Defense Forces gained confidence from the campaign. The war demonstrated that Israel was capable of executing large scale military maneuvers in addition to small night-time raids and counter-insurgency operations. David Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary that “90,000 British and French troops had been involved in the Suez affair. If they had only appointed a commander of ours over this force, Nasser would have been destroyed in two days.” The war also had tangible benefits for Israel. The Straits of Tiran, closed by Egypt since 1950, was re-opened to Israeli shipping. The Israelis also secured the presence of UN peacekeepers in Sinai, which brought an eleven year lull at its border with Egypt.

In my next post I will quickly outline the events between 1956 and the build-up to the Six Day War. Feel free to comment on these posts and let me know how I’m doing.

Great job, Chris! Can’t wait for the next chapter!