In my last post Read it here! I breezed through the major events from the end of the 1948 War to the spring of 1956. I will now delve into the next very important event in the history of Israel, the 1956 Suez Crisis. This was a very strange event that involved a country trying to immerge from decades of colonial rule (Egypt), a country surrounded by enemies trying to secure it’s existence, (Israel) and two world powers trying to maintain their empires, (Great Britain & France). It was a perfect storm of factors all coming together leading to a international incident that changed the history of every county involved as well as the world at large. First I’ll start with a little background information.

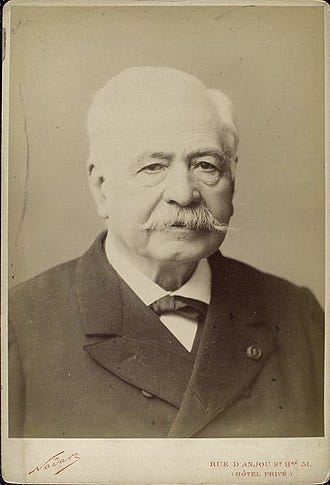

On November 17 1869, after ten years of work, the Suez Canal was opened, paid for by the French and Egyptian governments. In 1875, as a result of a growing national debt and a financial crisis, Egypt was forced to sell its shares in the Suez Canal Company (SCC) to the British. The UK obtained a 44% share in the SCC for £4 million ($569 million in 2020). With the 1882 annexation of Egypt, the UK took control of the country as well as the canal, but the SCC was still the day to day operators of the canal. The 1888 Convention of Constantinople, signed by all the colonial powers of the day, declared the canal was a neutral zone under British protection. It also maintained that all countries were allowed free passage through the canal in times of peace or war.

After World War II, Egyptian domestic politics were experiencing a radical change, driven by economic instability, inflation, and unemployment. Unrest began to manifest itself in the growth of radical political groups, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, and in an increasingly hostile attitude towards Britain and its presence in the country, as well as their role in the creation of Israel. A group of nationalist military officers known as the Free Officers Movement, started to believe that the monarchy was leading Egypt down a path to destruction.

One also needs to also take into consideration that in the 1950s, the political situation in the Middle East was dominated by four interlinked conflicts:

The Cold War, the geopolitical battle for influence between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The Arab Cold War, the race between different Arab states for the leadership of the Arab world.

The anti-colonial struggle of Arab nationalists against the two remaining imperial powers, Britain and France.

The Arab–Israeli conflict, the political and military conflict between the Arab countries and Israel.

In October 1951, the Egyptian government unilaterally voided the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, the terms of which had granted Britain a lease on Suez for 20 more years. Britain refused to withdraw from Suez, relying upon its rights outlined in the treaty, as well as the presence of the 80,000 troops of the Suez garrison. The price of such a course of action was a steady escalation in hostility towards Britain and British troops in Egypt, which the Egyptian authorities did little to curb.

On January 25 1952, for example, Brigadier Kenneth Exham, the British commander in the region, issued a warning to Egyptian policemen in Ismailia, demanding that they surrender their weapons and leave the canal zone. The reason for this was twofold. First, by having the police leave, the British were removing the only remaining manifestation of Egyptian authority in the canal zone. Secondly, they hoped to end the aid the police force was providing to Fedayeen groups involved in anti-British activity. The Mayor of Ismailia refused the request, as did Interior Minister Fouad Serageddin. As a result, a British force of 7,000 troops and tanks surrounded the police station occupied by 700 Egyptian police. Armed only with rifles, the Egyptians refused to surrender their weapons and General Exham ordered his troops to attack the buildings. Vastly outnumbered, the Egyptians continued to fight until they ran out of ammunition. The confrontation, which lasted two hours, left 50 Egyptians dead and 80 others injured and 650 Egyptian police arrested by the British.

The following day, news of the attack in Ismailia reached Cairo, provoking the ire of Egyptians. The unrest began at the Almaza Airport, where workers refused to provide services to four British airplanes. This was followed by a show of solidarity of policemen in the Abbaseya barracks. A large group of protestors gathered and headed to Cairo University, where they were joined by students. Both groups marched towards the prime minister's office to demand that Egypt break diplomatic relation with the United Kingdom and declare war on it. The Minister of Social Affairs told the protesters that the government wanted to do it, but were forbidden by King Farouk I. The protestors next marched to Abdeen Palace, where they were joined by students from Al-Azhar University. The protests then turned violent with a fire being set in the Casino Opera Club. The fire spread to the Shepheard’s Hotel, the Automobile club, Barclay’s Bank and many other shops, offices, hotels and banks. Fueled by anti-British and anti-Western sentiment most of the rioting was aimed at British property as well as any establishments with foreign connections or associated with Western influence. The fires also reached the neighborhoods of Faggala, Daher, Citadel, as well as Tahrir Square. Rioting and looting ran rampant until the Egyptian Army arrived to restore order.

A total of £3.4 million ($99.4 million in 2023 dollars) damage was done to British and foreign property. The damage included 300 shops, 30 corporate offices, thirteen hotels, 40 movie theaters, ten firearms shops, 73 coffeehouses and restaurants, 92 bars and sixteen social clubs. 26 people were killed and 552 people were wounded. Among the dead was 82-year old mathematician James Ireland Craig, who had invented the Craig retroazimuthal projection a device to enable Muslims to find the direction to Mecca and 552 were wounded.

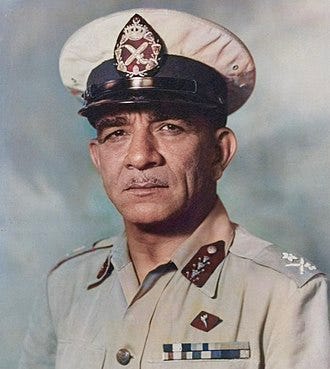

This incident, along with the corruption and incompetence of King Farouk's government, and his poor performance as overall commander of Egyptian forces in the 1948 war, proved to be catalysts for his removal. At 7:30 am on July 23 1952, future Egyptian President Anwar Sadat read a message on Cairo radio declaring a military coup led by General Mohamed Naguib and Lieutenant Colonel Gamal Abdul Nasser, had taken place. Sadat read:

Egypt has passed through a critical period in her recent history, characterized by bribery, mischief, and the absence of governmental stability. All of these were factors that had a large influence on the army. Those who accepted bribes and were thus influenced caused our defeat in the Palestine War. As for the period following the war, the mischief-making elements have been assisting one another, and traitors have been commanding the army. They appointed a commander who is either ignorant or corrupt. Egypt has reached the point, therefore, of having no army to defend itself. Accordingly, we have undertaken to clean ourselves up and have appointed to command us, men from within the army who's ability, character and patriotism we trust. The army will take charge with the assistance of the police. I assure our foreign brothers that their interests, their personal safety and their property are safe, and that the army considers itself responsible for them. May God grant us success

The announcement prompted celebrations and cheering crowds in the streets. Neguib, ordered Farouk to abdicate in favor of his six-month old son, Crown Prince Ahmed Faud, who would be knowns as King Faud I. Prince Muhammad Abdel Moneim was asked to led a three-man Regency Council until Faud gained his majority, however the Regency Council held only nominal authority. Real power lay with the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), led by Naguib and Nasser. The former king's departure into exile came at 6:00 pm on July 26 1952, when Farouk set sail for Italy on his yacht under the watchful eyes of the Egyptian Navy. On July 27 1952, the monarchy was officially abolished and the Republic of Egypt declared, with Naguib as President and Nasser as Vice President. After assuming power, the RCC expected to become the "guardians of the people's interests" against the traditional ruling class and pro-monarchy elements, while leaving the day-to-day tasks of government to civilians. They asked former Prime Minister Ali Maher to resume his previous office, and to form an all-civilian cabinet. Unfortunately, over time, relations between the RCC and Maher grew tense, as the latter viewed many of the RCC's proposals; abolition of the monarchy, agrarian reform, land reform and reorganization of political parties, as too radical. This came to a head on September 7 1952, with Maher's resignation. Naguib assumed the additional role of prime minister, and Nasser that of deputy prime minister. Later that month, the Agrarian Reform Law came into effect, and gave the RCC, in their eyes legitimacy, transforming the coup into a revolution.

Another project that the RCC (read Nasser) was very interested in, was a replacement dam on the Nile river. In 1902 the British had built the Low Dam across the Nile at the city of Aswan. By the 1950s, the dam had outlived its usefulness and was in danger of being overwhelmed by the rising waters behind it. A new dam was high (no pun intended) on the list of projects the RCC wished to complete. With the ability to better control flooding, providing increased water storage for irrigation and the ability to generate hydroelectric power, the dam was seen by the RCC as pivotal to Egypt's planned industrialization. In addition the RCC was convinced that the Nile waters had to be stored in Egyptian territory for political reason. In 1952, the Greek-Egyptian engineer Adrian Daninos began to develop plans for a new dam called the Aswan High Dam, and within two months, the plan was accepted. Initially, both the US and the USSR were interested in helping with development of the dam, but complications ensued due to their Cold War rivalry, as well as growing intra-Arab tensions.

There were two other players involved in the build up to the Suez Crisis. The United States and the Soviet Union, they would not be directly involved in the action, but acted as two large elephants in either corner of a room. They couldn't be ignored, everyone had to decide which elephant they supported. Israel, especially, wished for their money and arms, but otherwise wanted to be left alone by both. Egypt’s plan on the other hand, was to play the superpowers off one another to compete for Egypt’s friendship.

The main aim of the US was keeping the Middle East free of Soviet influence. The central problem for American policy in the Middle East was the fact that the two strongest powers in the region, Britain and France, were also the nations whose influence most locals resented the most. Another major dilemma for American policy was the fact that the United States military was spread too thin. The doctrine at the time, was for the US to be able to fight two large regional wars simultaneously, or one continental scale war, but because of commitments in Europe and Asia, the US lacked a sufficient number of deployable troops and equipment to resist a Soviet invasion of the Middle East. In an attempt to offset the lack of available troops, the idea of forming a NATO-like pact in the Middle East, came into favor. It was called the Middle East Defense Organization, (MEDO) and Egypt was viewed as the key to it's formation. The thought was, if the US could get Egypt to sign on to this venture, then the other countries in the region would fall into line and also join MEDO. From 1953 onwards, American diplomacy had attempted unsuccessfully to persuade the powers involved in the Near East, both local and imperial, to set aside their differences and unite against the Soviet Union. The Americans took the view that, just as fear of the Soviet Union had helped to end the historic Franco-German enmity so too could anti-communism end the more recent Arab–Israeli dispute. In the 1950s it was a source of constant puzzlement to American officials that the Arabs and the Israelis seemed more interested in fighting each other than uniting against the Soviet Union. After his visit to the Middle East in May 1953 to drum up support for MEDO, Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles found, much to his astonishment, that the Arab states were "more fearful of Zionism than of the Communism".

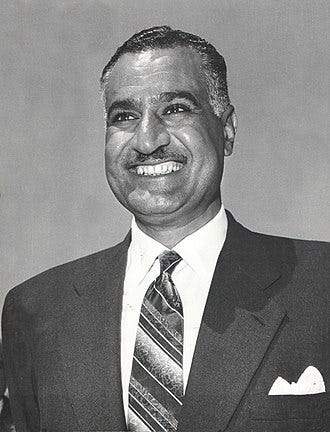

In Egypt, Nasser had cultivated friendship with CIA officers in Cairo in an effort to have America act as a restraining influence on the British, should Britain decide to intervene and put a stop to the revolution (until Egypt renounced it in 1951, the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty allowed Britain the right of intervention against all foreign and domestic threats). These friendships led Washington to vastly overestimate its influence in Egypt. In May 1953, during a meeting with Secretary of State Dulles, to float the idea of Egypt joining MEDO, Nasser responded by saying that the Soviet Union has:

never occupied our territory but the British have been here for seventy years. How can I go to my people and tell them I am disregarding a killer with a pistol six feet from me, to worry about somebody who is holding a knife a thousand miles away?

Obviously, Nasser did not share Dulles's fear of the Soviet Union and insisted quite vehemently that his goal was to see the end of all British influence, not only in Egypt, but the whole Middle East. Nasser made it clear to the US that he wanted an Egyptian-dominated Arab League, to be the principal defense organization in the Near East. A league that might be informally associated with the United States but no more.

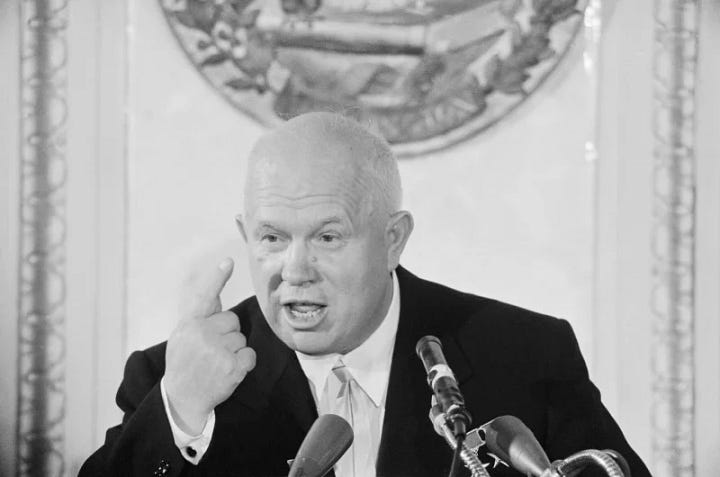

At the same time, the Soviet Union, under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev, was making a concerted effort to win influence in the Third World. As part of this diplomatic offensive, Khrushchev had abandoned Moscow's traditional line of treating non-communists as enemies and adopted a new tactic of befriending "non-aligned" nations, countries led by leaders who were not communists, but in varying degrees were hostile towards the West. Khrushchev made it clear, that under the red banner of anti-imperialism, the Soviet Union would provide arms to any government in the Third World as a way of undercutting Western influence.

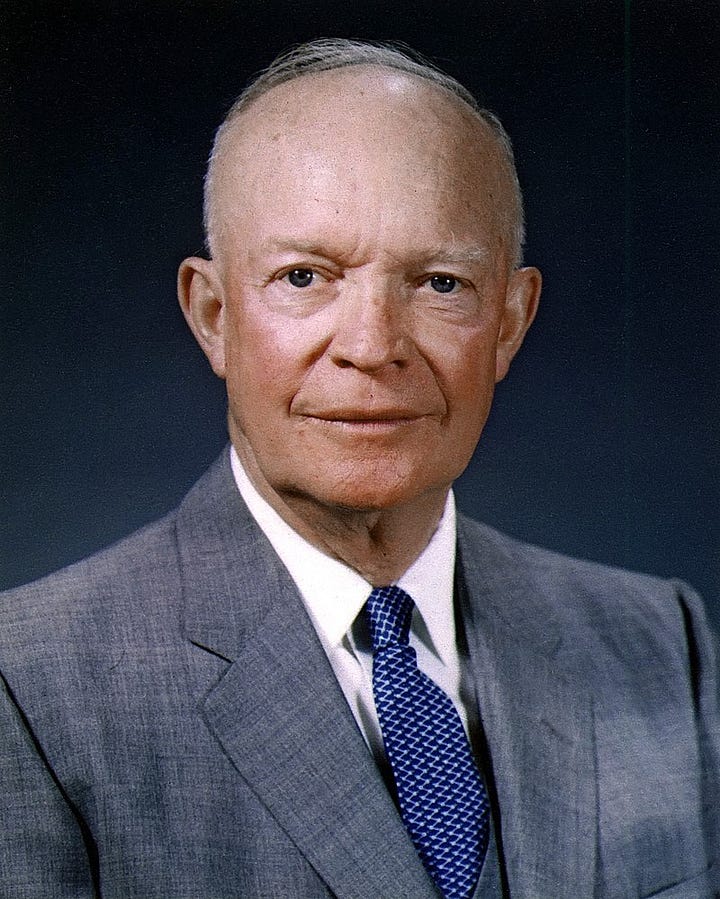

Traditionally, most of the equipment in the Egyptian military had come from Britain, but the RCC’s desire to break British influence in Egypt meant that they were desperate to find a new source of weapons to replace Britain. Their first choice for buying weapons was the United States. However Vice President Nasser’s frequent anti-Zionist speeches and sponsorship of the Fedayeen guerillas and their raids into Israel, made it difficult for the Eisenhower administration to get the Congressional approval necessary to sell weapons to Egypt. President Eisenhower and Dulles told Nasser that the US would supply him with weapons only for defensive purposes and only if American military advisors accompanied them for supervision and training. Nasser rejected those conditions, and said he would ask the USSR for support. In reality, Nasser’s move was s a way of pressuring the Americans into selling them the arms they desired. However, Khrushchev was more than ready to arm Egypt, if the Americans proved unwilling.

In October 1954, Britain and Egypt concluded the Anglo-Egyptian Agreement concerning the phased evacuation of British Armed Forces from the Suez base. The terms of the agreement stated that all troops would be withdrawn within 20 months, maintenance of the base was to be continued, and Britain had a right to return under extraordinary circumstances until 1961. The Suez Canal Company, the company that actually ran the canal and made the money, was not due to revert to Egyptian control until November 16 1968.

By late 1953, the situation between Muhammad Naguib and the rest of the RCC, especially Gamal Nasser, had started to sour. Naguib began distancing himself from proposed land reform decrees, as well as drawing closer to Egypt's established political forces, namely the Wafd Party and the Muslim Brotherhood. In late 1953 the RCC (again, read Nasser) resolved to depose him. Nasser accused Naguib of supporting the recently outlawed Muslim Brotherhood and of having dictatorial ambitions. The charges made Naguib unpopular both in the RCC and with the Egyptian people but there was no concrete evidence to support them and the situation continued as before until a fateful day in the fall.

On October 26 1954, Mahmoud Abdel-Latif, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood , attempted to assassinate Nasser while he was delivering a speech in Alexandria to celebrate the British military withdrawal, a speech that was broadcast live to the entire Arab world on radio. The gunman was 25 feet away from him and fired eight shots at Nasser, luckily all eight missed. Panic broke out in the large audience, but Nasser maintained his posture and raised his voice to appeal for calm. With great emotion he exclaimed the following:

My countrymen, my blood spills for you and for Egypt. I will live for your sake and die for the sake of your freedom and honor. Let them kill me; it does not concern me so long as I have instilled pride, honor, and freedom in you. If Gamal Abdel Nasser should die, each of you shall be Gamal Abdel Nasser. Gamal Abdel Nasser is of you and from you and he is willing to sacrifice his life for the nation.

The crowd roared in approval and Arab audiences were electrified. The assassination attempt backfired, quickly playing into Nasser's hands. When he returned to Cairo, he ordered one of the largest political crackdowns in the modern history of Egypt with the arrests of thousands of dissenters, mostly members of the Brotherhood, but also communists, and other Nasser opponents. Eight Brotherhood leaders were sentenced to death, although the sentence of its chief ideologue, Sayyid Qutb, was commuted to a 15-year prison sentence. Naguib was removed from the presidency and put under house arrest, but was never tried or sentenced. 140 officers loyal to Naguib were dismissed, and no one else in the army rose to defend them. With his rivals neutralized, Nasser became the undisputed leader of Egypt. However, Nasser's following among the common people, was still too small to sustain his plans for reform and to secure him in office. To promote himself, he gave Liberation Rally speeches in a cross-country tour. Arab nationalist terms such "Arab homeland" and "Arab nation" began to frequently appear in his speeches. In speeches before October 26, he would refer to the Arab "peoples" or the "Arab region". With his domestic position considerably strengthened, Nasser was able to secure primacy over his RCC colleagues and gained relatively unchallenged decision-making authority particularly over foreign policy. In January 1955, the RCC appointed him as their president. In January 1956, the new Constitution of Egypt was drafted, establishing a single-party system under the National Union (NU). A movement Nasser described as the "cadre through which we will realize our revolution". Nasser's nomination for President and the new constitution were put to a vote on June 23, each was approved by an overwhelming majority, with Nasser receiving 99.9% of the vote.

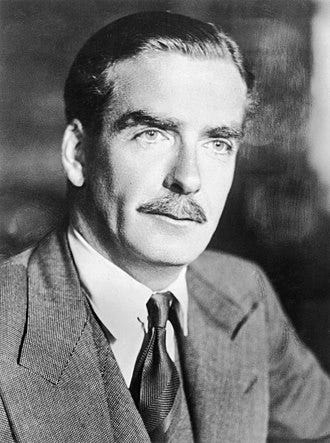

In March of 1956, French Premier Guy Mollet, was facing a serious rebellion in their colony of Algeria. National Liberation Front (FLN) rebels were being financed and inspired by Egypt and daily propaganda broadcasts were being beamed into Algeria via Voice of the Arabs radio. Egyptian owned ships were clandestinely shipping arms to the FLN, therefore Mollet saw Nasser as a major threat to France. During a visit to London in March 1956, Mollet told British Prime Minister Antony Eden, “France is faced with an Islamic threat to the very soul of the country.” Mollet went on to say, “his (Nasser’s) ambition is to recreate the conquests of Islam. But his present position is largely due to the West’s policy of building him up and flattering him".

Starting as early as 1949, France and Israel had started moving towards an alliance. By late 1954 France was shipping thousands of arms, tons of ammunition and even jet fighters to Israel. In November 1954, the Director-General of Israel's Ministry of Defense Shimon Peres visited Paris, where he was received by the French Defense Minister Marie-Pierre Koenig. Koenig informed Peres that France would sell Israel any weapons it wanted to buy. In April 1956, during another visit, Peres informed the French that Israel had decided that war with Egypt was inevitable and must begin before 1956. Peres insisted that Nasser was a genocidal maniac intent upon destroying Israel, and exterminating its people, and Israel believed that their only hope was to fight the war before Egypt received an overwhelming number of Soviet weapons, and there was still a possibility of victory. Peres asked for the French, who had emerged as Israel's closest ally by this point, to give Israel all the help they could, in the coming war.

On May 16 1956, Egypt officially recognized the People's Republic of China, which angered the US. The Eisenhower administration had also become very annoyed at Nasser's efforts to play the United States off against the Soviet Union. The administration believed that even if Nasser were able to secure Soviet economic support for the High Dam, it would be beyond the capacity of the Soviet Union to support, and in turn would strain Soviet-Egyptian relations. As early as September 1955, when Nasser announced the purchase of $320 million in Soviet military equipment via Czechoslovakia, Dulles had wrote that competing for Nasser's favor was probably going to be "an expensive process", and one that Dulles wanted to avoid as much as possible. In June 1956, the Soviets offered Nasser $1.12 billion at 2% interest for the construction of the Aswan dam.

By mid-1956, Nasser was frustrating British attempts to invite Jordan into the Baghdad Pact, (a defense organization of their own, comprising the UK, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and Turkey), by financing large anti-monarchy demonstrations in Amman. Egged on by the Egypt-based (and Nasser, directed) Voice of the Arabs Radio, the rioting became so severe, that King Hussein felt he must make concessions, to save his throne. He decided to relieve all the British officers of the British led, Arab Legion, including the commander, General Sir John Bagot Glubb, throwing Britain's security policy in the Middle East into disarray. However, in private, Hussein assured the British that he was still committed to continuing the traditional Hashemite alliance with Britain.

British Prime Minister Antony Eden was especially upset at the sacking of Glubb, which he saw as a grievous blow to British influence, Eden became consumed with a hatred for Nasser, and from March 1956 onwards, was in private, committed to his overthrow. As one British politician recalled:

For Eden, this was the last straw… This reverse, he insisted was Nasser's doing … Nasser was Enemy No. 1 in the Middle East, Eden believed Nasser would not rest until he destroyed all our friends and eliminated the last vestiges of our influence … Nasser must therefore be destroyed.

Increasingly Nasser came to be viewed in British circles—and in particular by Eden—as a dictator, akin to Benito Mussolini. The left-wing press in England, went so far as to actually make the comparison between the two, and, Anglo-Egyptian relations would continue on their downward spiral. Britain who was eager to tame Nasser, looked towards the United States for support. However, Eisenhower strongly opposed any military action against Egypt and were having trouble of their own dealing with Nasser.

On July 19 the US State Department announced that American financial assistance for the High Dam was "not feasible in present circumstances." After this announcement, Nasser was left bitter by the fact that the United States had reneged on their promise to assist in funding the construction of the Aswan High Dam, even though it was actions by Nasser himself, antagonizing Britain, accepting aid from the Soviet Union and buying arms from Czechoslovakia, that led to the decision to reverse funding. Nasser decided that the West must be punished for their actions which he viewed as an attempt to recolonize the Arab world. One plan brought forward for his consideration was the nationalization of the Suez Canal. It was believed that this would teach the West a lesson about interfering in Arab affairs and that the fees from the operation of the canal could be used to offset the cost of the Aswan dam. Nasser order the military to train a unit that would occupy the buildings around Egypt that the Suez Canal Company used to run the canal. By July 25 such a unit was created and ready to go, they were just waiting for Nasser to give the go ahead. If he decided to move forward with the operation, Nasser himself would speak the code words in a speech the next day. The words to begin the operation would be the name of the Frenchman who built the canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps.

On July 26, in Alexandria, at nine in the evening, with night slowly falling over the vast Mohammed Ali Square, a huge crowd is waiting for their leader to deliver a speech addressing the recent announcement by the US State Department of the cancelling of funding for the Aswan Dam. The speech was also broadcast on Voice of the Arabs radio and units around the country waiting patiently to hear the password and begin their takeover of the canal. Two hours into the speech President Nasser was complaining of the treatment Egypt had received at the hands of the World Bank and their President Eugene Black, the World Bank had also withdrawn funding for the dam after US pressure, Nasser said:

“Mr. Black reminded me of Ferdinand de Lesseps”

The speech reached a bitter, vicious and furious crescendo. Nasser rails against “the imperialists who have mortgaged our future”. At first the crowd reacts tentatively, expecting Nasser to end his anti-US diatribe by announcing pro-Soviet action, and why has he invoked de Lesseps?

“We will reclaim the profits that this imperialist company, this state-within-a-state, made while we were starving to death. I would like to announce that the Official Gazette is at this very moment publishing a statute nationalizing the Suez Canal Company. At this very moment government agents are taking possession of the Company’s offices!” “The Suez Canal will pay for the Aswan dam project. Four years ago, King Farouk fled this country from this spot. Tonight I am wresting control of the Company on behalf of the Egyptian people. Tonight the Suez Canal will be managed by Egyptians!”

He also announced that all assets of the Suez Canal Company had been frozen, and that stockholders would be paid the price of their shares according to the day's closing price on the Paris Stock Exchange. That same day, Egypt curtailed Israeli shipping, in three ways. They closed the Suez canal, closed the Straits of Tiran and blockaded the Gulf of Aqaba. All in contravention of the Constantinople Convention of 1888. Many argued it was also a violation of the 1949 Armistice Agreement between Egypt and Israel.

Thirty minutes earlier, when Egyptian radio had broadcast the momentous sentence: “Mr. Black reminded me of Ferdinand de Lesseps.” The commando units sprung into action, occupying the Suez Canal Company’s headquarters in Cairo and offices in Ismailia, Port Said, Port Tewfik and Suez.

The nationalization was a huge surprise to Britain, it had not even been a topic of discussion in Cabinet meetings and there had been no talk of the canal at the Commonwealth Prime Minister’s Conference in London in late June and early July. Egypt's action, however, threatened British economic and military interests in the region. Prime Minister Eden was under immense domestic pressure from Conservative MPs who drew direct comparisons between the events of 1956 and those of the Munich Agreement of 1938.

Eden was hosting a dinner for King Feisal II of Iraq and his Prime Minister, the Nasser arch-enemy, Nuri es Said, when he learned the canal had been nationalized. They both unequivocally advised Eden to "hit Nasser hard, hit him soon, and hit him by yourself" – a stance shared by the vast majority of the British people in subsequent weeks. However, the opposition in Eden’s government, the Labor Party issued a statement on August 8 stating that forcing Nasser to denationalize the canal against Egypt's wishes would violate the UN charter. Direct military intervention also ran the risk of angering Washington and damaging Anglo-Arab relations. As a result, the British government concluded that their only course of action was to negotiate a secret military pact with France aimed at regaining control over the Suez Canal. Since the United States did not wish to support the British protests regarding the canal. Eden believed a military intervention against Egypt was the only way to avoid the complete collapse of British prestige in the region.

Among the "White Dominions" of the British Commonwealth, Canada had few reasons to view the Suez canal as important to them, and had twice refused British requests for peacetime military aid in the Middle East. By this time Australia and New Zealand viewed the Panama canal as much more strategically important to them than Suez. However, the memory of both nations fighting in two world wars to protect a canal which many still called their "lifeline" to Britain or the "jugular vein of the British Empire", contributed to Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies and New Zealand Prime Minister Sidney Holland, supporting Britain in the early weeks following the seizure. On August 7, Holland hinted to his parliament that New Zealand might send troops to assist Britain. South Africa's Prime Minister Johannes Strijdom stated "it is best to keep our heads out of the beehive". His government saw Nasser as an enemy but South Africa would benefit economically and geopolitically from a closed Suez canal, and benefit diplomatically from not drawing attention to interfering in another nation's internal affairs.

The "non-white Dominions" saw Egypt's seizing of the canal as an admirable act of anti-imperialism, and Nasser's Arab nationalism as similar to Asian nationalism. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (he of the famous jackets), was with Nasser when he learned of the Anglo-American withdrawal of aid for the Aswan Dam. Nehru was publicly neutral, even though India was a major user of the canal. His only statement on the issue, was a warning that any use of force, or threats, could be "disastrous". The Prime Minister of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike also viewed Suez as very important to the economy, so its government was not as vocal in supporting Egypt as it would have been otherwise. Pakistan was also cautious about supporting Egypt given the rivalry between the two nations as leading Islamic countries, but its government did state that Nasser had the right to nationalize the canal.

The French Prime Minister Guy Mollet, outraged by Nasser's move, was determined that Nasser would not get his way. The French public was supportive of Mollet, and all of the criticism of his government came from the right, who publicly doubted that a socialist like Mollet had the guts to go to war with Nasser. During an interview with publisher Henry Luce, Mollet held up a copy of Nasser's book Egypt's liberation: The Philosophy of the Revolution and said: "This is Nasser's Mein Kampf. If we're too stupid not to read it, understand it and draw the obvious conclusions, then so much the worse for us."

On July 28 1956, Mollet and his cabinet decided on military action against Egypt in alliance with Israel. Admiral Nomy of the French Naval General Staff was sent to Britain to inform Eden of France's decision, and to invite them to cooperate if they were interested. At the same time, Mollet was offended by what he considered to be the lackadaisical attitude of the Eisenhower administration to the nationalization of the canal. The reason Mollet was offended, revolved around an incident earlier in 1956. Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov had offered the French a deal. Moscow would end its support of the FLN rebels in Algeria, if Paris would take a more "semi-neutral" position in the Cold War. Given the fact that Algeria (which the French considered an integral part of France) had become a place of increasingly savage violence, and that violence had even spilled over into France itself, the Mollet administration had felt tempted by Molotov's offer, but in the end, Mollet had chosen to remain firmly in the NATO camp. In Mollet's view, his fidelity should have earned him the right to expect firm American support against Egypt. When the American proved less than forthcoming with any support at all, he became even more determined that France would act, on their own, if necessary, to regain control of the canal.

Britain was anxious to solve the problem quickly lest it lose efficient access to the remains of its empire, and both Britain and France were eager that the canal should remain open as an important conduit of oil. Both countries also believed that Nasser should be removed from power. The French held the Egyptian president responsible for assisting the FLN rebellion in Algeria and were nervous about the growing influence that Nasser exerted on their other North African colonies and protectorates.

While the United States did not want to support France or Britain, against Egypt directly, the Eisenhower administration did not sit idly by, and quickly suggested calling a conference of maritime nations, in an attempt to find a diplomatic solution to the Suez issue. The British preferred to invite only the most important countries, but the Americans believed, inviting as many countries as possible with maximum publicity, would more quickly move world opinion to the Anglo-French position. Invitations went to the England, France, the Netherlands and Spain the four remaining countries of the original signatories of the Constantinople Convention and the 16 largest users of the canal. Representatives of the 20 nations met in London from August 16 to 23. 15 of the nations supported the American, British and French proposal of international operation of the canal. Ceylon, Indonesia, and the Soviet Union supported India's competing proposal, which Nasser had pre- approved, for, international supervision only. India criticized Egypt's seizure of the canal, but insisted that its ownership and operation should not change now. The majority of countries chose Australian PM Menzies to negotiate with Nasser in Cairo, while the proposal for international operation of the canal would go to the Security Council. Menzies issued a communique to Nasser on September 7, presenting a case for compensation for the Suez Canal Company and the "establishment of principles" for the future use of the canal ensuring it would "continue to be an international waterway operated free of politics or national discrimination, with a financial structure so secure and a level of international confidence so high that an expanding and improving future for the Canal could be guaranteed". It called for a convention to recognize Egyptian sovereignty over the canal, but suggested the establishment of an international body to run the canal. Nasser saw such measures as a "degradation of Egyptian sovereignty" and rejected the proposals. The United States continued to work through diplomatic channels to resolve the crisis without resorting to conflict and proposed another plan, this time an association of canal users that would set rules for its operation. Fourteen other nations agreed, Britain, in particular supported this plan. They supported the plan because they believed that any violation of the association rules would result in the use of military force, but after Eden made a speech to this effect in parliament on September 12, US ambassador Dulles insisted "we do not intend to shoot our way through (the canal)”. The British and French reluctantly agreed to pursue the diplomatic avenue but viewed it as merely an attempt to buy time, during which they continued their military preparations.

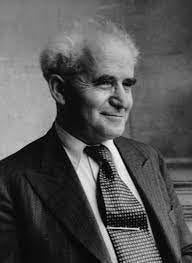

Israel, the country that was the most immediately effected by Egypt's measures, wanted to reopen the Straits of Tiran and the Gulf of Aqba to Israeli shipping. David Ben-Gurion saw the opportunity to strengthen Israel's southern border and to weaken what it saw as a dangerous and hostile state. The Israelis were also deeply troubled by Egypt's procurement of large amounts of Soviet weaponry, including 250 tanks, 500 artillery pieces, 150 MiG-15 jet fighters, 50 Ilyushin IL-28 bombers, submarines and other naval craft. The influx of this advanced weaponry altered an already shaky balance of power. Israel believed it had only a narrow window of opportunity to attack Egypt. In addition, Israel believed Egypt had formed a secret alliance with Jordan and Syria and planned for another multi-front war like in 1948.

Britain used the time, while the US tried to find a diplomatic solution, to prepare a plan for the coming conflict. They came up with Operation Revise. It called for the following:

Phase I: Anglo-French air forces to gain air supremacy over Egypt's skies. Called Operation Musketeer.

Phase II: Anglo-French air forces were to launch a 10-day "aero-psychological" campaign called Operation Musketeer II

Phase III: Air- and sea-borne landings to capture the canal zone. Called Operation Telescope.

Operation Musketeer was to be a two-day air campaign that would see Britain and France gain air superiority. Musketeer II called for interdiction sorties all over the country to cripple the Egyptian economy and demoralize the population. Operation Telescope called for the capture of Alexandria by a naval landing. Once the city had been taken, British armored units would seek a decisive battle with Egyptian forces. However, Revise as originally planned, was considered to heavy handed and involved too many troops. General Sir Charles Keightley, the British Commander in Chief for the Middle East and French Defense Minister Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury were opposed to Operation Revise, because of its open-endedness and the fact that there was no clear goal beyond seizing the canal zone. However, the plan was embraced by Eden and Mollet as offering greater political flexibility and the prospect of lower Egyptian civilian casualties. On September 8 1956 after further consultations, the British and French governments approved Operation Revise II, a scaled back operation, with far fewer troops involved.

On October 22 1956, Prime Minister of Israel David Ben-Gurion, Director General of the Ministry of Defense Shimon Peres and Chief of Staff of the IDF Moshe Dayan travelled from Israel to an isolated house in the Paris suburbs, to meet French Minister of Defense Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury, Minister of Foreign Affairs Christian Pineau, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces General Maurice Challe and British Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd.

Together they secretly planned a two part invasion of Egypt. First, Israel would invade the Sinai peninsula, then Britain and France would enter Egypt on the pretext of "separating the combatants and protecting the canal”. One of the most painstaking aspects was formulating a plan both Britain and Israel could agree on. The Israelis distrusted the British but, because the French were not prepared to act without them, the Israelis were forced to deal with the British. The UK was also wary of an alliance with Israel, because the United Kingdom maintained strong links with a number of Arab countries, they believed that any involvement with Israel might damage those links. After 48 hours of negotiations and compromise, a seven-point agreement was signed by Ben-Gurion, Pineau and Lloyd. Israel, who was concerned that they would be abandoned in the middle of their invasion, insisted that each group leave Paris with a signed copy, written in French. Although not part of the protocol, the occasion also allowed Israel to secure a French commitment to construct the Negev Nuclear Research Center and to supply natural uranium for it.

Under the agreement the following timetable was authorized:

October 29: Israel to launch Operation Kadesh, the invasion of Sinai.

October 30: Anglo-French ultimatum to demand both sides withdraw from the canal zone.

October 31: Britain and France begin Revise.

General Sir Hugh Stockwell was given command of the British ground forces tasked to the operation and General Andre Beaufre was in command of all French forces.

The scene for this strange event is now set, and next week I will recount one of the oddest and least known events of the last 70 years.

I hope everyone are enjoying these posts. Please comment below if you have anything to say. Don't be shy, I'm not a bad guy and without your comments it seems like I'm just writing this for myself. Of course I am writing for me, but you are just as important in this process. I want to know what you like, what you hate, what I could do better or why you read this.

This is strong work!! I’m learning so much detail about an historical period I thought I had a pretty good grasp of, but the insights I gain here are so valuable. This area of the world is so much a part of human history and remains so today - thanks for your superb efforts!