What's Wrong With the Government Part II

I'm not saying it was the Progressives, but it was the Progressives.

Part I looked at how the government is supposed to work. Click below if you missed it.

Today I will begin to look at what went wrong. This is a long and complicated story so bear with me.

What went wrong?

The Progressives:

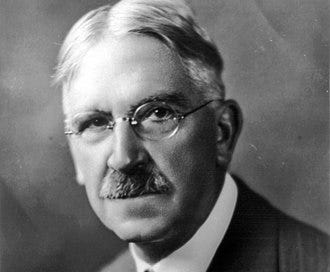

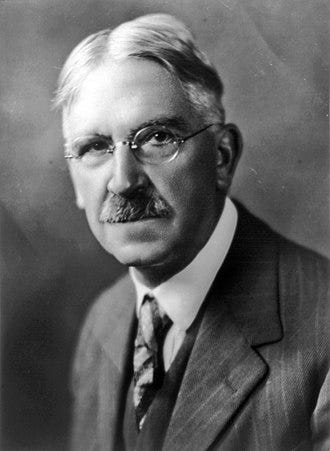

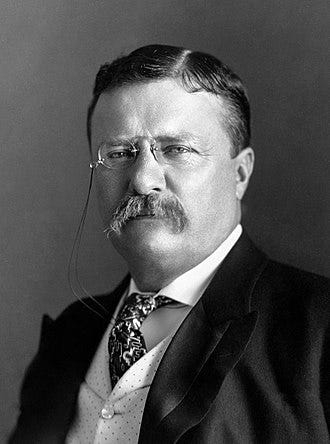

When I say Progressives, I don't mean they raving lunatics that call themselves Progressives today. I mean Democrats and Republicans of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries who believed that the United States has outgrown the Constitution and that in the future, science and experts would run the country. In the United States, progressivism began as a rebellion against Constitutionalism as expressed by John Locke and the Founders of the American Republic. Progressives have an absolute belief that Man and society can be perfected, “if we can all just work together”. They have no use for God in any form, unless it is worship of the State. They also think that if the whole world would just adopt their beliefs and policies than the world would literally be a better place. Progressivism holds a dim view of individual rights and private property, they replace it with group rights and the need for everyone to cooperate to achieve progressive goals, including forced “cooperation” if necessary. The most influential Progressives were Thomas Dewy, Herbert Croly and future presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

Wilson was especially influential, in his doctoral dissertation Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics he laid out all the problems he saw with the system of government designed by the Founders. As a professor of Jurisprudence and Political Economy at Princeton he wrote several other influential books which were also critical of the American constitutional structure. Wilson was strongly influenced by 19th century German intellectual thought, especially Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s views of the State as the vehicle of an Idea through history, and by adaptations of Darwinian theories to social science. In fact, he was so besotted with German philosophy and university research that his wife, Ellen, learned the language just to translate German works of political science for him. Wilson enthusiastically embraced the new ideology of the State. He characterized progressive government as organic, and contrasted it with what he described as the mechanical nature of the Constitution and its structure of interacting and counterbalancing parts.

As he wrote in Constitutional Government in 1908, “The trouble with [the Framers’ approach] is that government is not a machine, but a living thing. It falls, not under the theory of the universe, but under the theory of organic life. It is accountable to Darwin, not to Newton.” In 1912 presidential nominee Woodrow Wilson announced in his campaign platform that “This is nothing short of a new social age, a new era of human relationships, a new stage-setting for the drama of life.” The “organic” State tied to the people in some mystical union must not be constrained by an old piece of parchment with its deceit of checks and balances. An entirely new constitutional order must be created that reflects the superiority of the State in human affairs. If that was not a realistic option because of political forces or sentimental popular attachments, the parchment must be heavily amended. During Wilson’s first presidential term, constitutional amendments to authorize a federal income tax and to elect Senators by popular vote were approved. Beyond formal amendment of the Constitution, all the components of the government had to be marshaled into the service of Progressivism, including Congress passing far-reaching laws that would increase the power of the state, even at the expense of individualism. The result was a series of federal regulatory laws in regard to labor laws, antitrust, child labor, taxes, and through the creation of the Federal Reserve system, banking. This activism was repeated in many states and the era of big government had arrived.

While the Founders believed that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights as well as a moral order that was discovered by Man with the gifts given to them by Nature and Nature's God. They also believed that each person had a duty to respect those rights in other people. The Progressives rejected these claims as naïve and unhistorical. In their view, humans are not born free, John Dewey wrote “that freedom is not something that individuals have as a ready-made possession, it is something to be achieved." They believed that Man is a product of his own history, through which he creates himself and to quote Dewey again, "Natural rights and natural liberties exist only in the kingdom of mythological social zoology."

The Progressives regarded the Founders' ideas as faulty because of the Founders' supposed failure to recognize the primary role of society over individualism. This also led them to ridicule the Founders' insistence on limited government. As Dewey writes, "the state has the responsibility for creating institutions under which individuals can effectively realize the potentialities that are theirs. It is true that social arrangements, laws and institutions are made for man, rather than that man is made for them, these laws and institutions are not means for obtaining something for individuals, not even happiness. They are means of creating individuals. Individuality in a social and moral sense is something to be wrought out.” "Creating individuals" versus "protecting individuals" sums up the difference between the Founders' and the Progressives' conception of what government is for.

Because the Founders believed that men by our very nature, are free, they thought that the political structure of society should be a social compact, with the government run by laws, voted on by locally elected officials who would be held accountable by frequent elections. The Progressives treated the social compact idea with scorn. Charles Merriam, a leading Progressive political scientist, wrote: “The individualistic ideas of the "natural right" school of political theory, indorsed in the Revolution, are discredited and repudiated. The origin of the state is regarded, not as the result of a deliberate agreement among men, but as the result of historical development, instinctive rather than conscious; and rights are considered to have their source not in nature, but in law.”

In Progressive Democracy published in 1914, Herbert Croly’s premise rested on the usual Progressive ideas, such as the omnipotent, all-caring, and morally perfect God-state that would be the inevitable evolutionary end of Progressive politics. Croly insisted, the Constitution’s structure of representative government and separation of powers needed to be, and would be, changed. Unlike the realities of the late 18th century which had produced American republicanism, “In the twentieth century, however, these practical conditions of political association have again changed, and have changed in a manner which enables the mass of the people to assume some immediate control of their political destinies.” Croly believed direct democracy was the most authentic expression of popular will and would eventually replace the old system of republican government. Croly stated that a government must have the “politics of meaning” and that “a social policy is concerned in the most intimate and comprehensive way with the lives of the people. In order to be successful, it must rest on the basis of abundant and cordial popular support.” Croly also believed that the direct democracy was to be little more than a vote on actions to be taken by a legislature otherwise unrestrained by the Law. He wrote in Progressive Democracy “The government must have the power to determine the Law instead of being circumscribed by the Law”. The Progressives believed that the business of the nation was getting so complicated that the Founders’ traditional way of governance was no longer able to answer the demands of such a technological society. They had confidence that modern science had superseded the knowledge of the liberally educated statesman and politics was regarded as too complex for the common man to cope with. Democracy for the Progressives meant that the people would take power out of the hands of locally elected officials and political parties and place it instead into the hands of the central government, which would in turn establish administrative agencies run by “neutral experts”, scientifically trained, to know what is best for the people and turn that into concrete policies. Local politicians would be replaced by neutral city managers presiding over technically trained staffs. Politics in the sense of favoritism and self-interest would disappear and be replaced by the universal rule of enlightened bureaucracy. Croly recognized, legislatures would not be up to the task of supervising such an increasingly intrusive nanny State. Only those educated in the top universities, preferably in the social sciences, were thought to be capable of governing. Therefore, a powerful administrative apparatus was required. This vast, unelected bureaucracy, which was purposefully beyond the control of the people, would use their expertise to answer the technological questions facing turn of the century America.

Yes, it might be a dictatorship of the technocratic elite, but it would be a benevolent one, Croly assured us that it would be “always loyally and selflessly laboring for our welfare.” This is also a total rejection of the beliefs of the Founding Fathers, especially James Madison, who believed that human nature was imperfect and political elites would always seek to secure greater political power, the entire reason the system of checks and balances was enshrined into the Constitution.

“If Men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and the next place, oblige it to control itself.”

James Madison

The Legislature:

Article I, Section 1 of the Constitution declares that “all legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress.” The Constitution therefore requires that legislative powers granted in our founding document be exercised by Congress and by Congress only. Congress cannot rightfully delegate its legislative powers to another authority. The administrative state violates this principle of non-delegation by placing legislative powers in the hands of unelected bureaucrats. The principle of non-delegation reflects the Framers’ commitment to the idea that sovereignty resides in the people alone and cannot be placed elsewhere. The people are the only source of political authority, and government possesses only the power that the people consent to give it. Governments, as the Declaration of Independence says, derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” In coming together to form a government, the people never relinquish their power; their natural rights are “unalienable.” They merely vest power in the hands of trustees.

By the end of the 19th Century the Progressives felt profound dissatisfaction with the operation of Congress. In Wilson’s Congressional Government he states, that the Congress is a secretive body where the committee chairmen have absolute power over their fiefdoms and everything of note happens behind closed doors. When there is debate, Wilson says it is like theater, scripted and just for show, and that no one is willing to make bold assertions or persuade anyone. He instead, prefers the English parliamentary system, where a strong Prime Minister is very much the leader of the government as well as the leader of the majority party within the legislature.

Wilson contrasts this with the American system where the committee chairmen are in charge, but he says that the real power behind the government are the political parties and especially the movers and shakers, or wire pullers as Wilson calls them, of each party. Wilson’s solution to this “problem” was to install a British-style cabinet government where the Congressional and Executive leaders are consolidated into one body, therefore making it much easier to conduct the business of Congress. In Wilson’s model, if a specific leader was unable to implement a policy, than that leader would resign. In other words, if a leader was in favor of a certain policy and the policy was repudiated by the people after a referendum, that leader would do what is best for the country and resign, since he could not command the respect of his party if he had been defeated.

Starting in the 1880s and especially the 1890s, in what became known as the Progressive Era, the Progressives thought the Speaker of the House would provide the leadership found in the Prime Minister in the British system. Speakers were so powerful that they were often referred to as “czars,” a reference to the autocratic rulers of Russia.

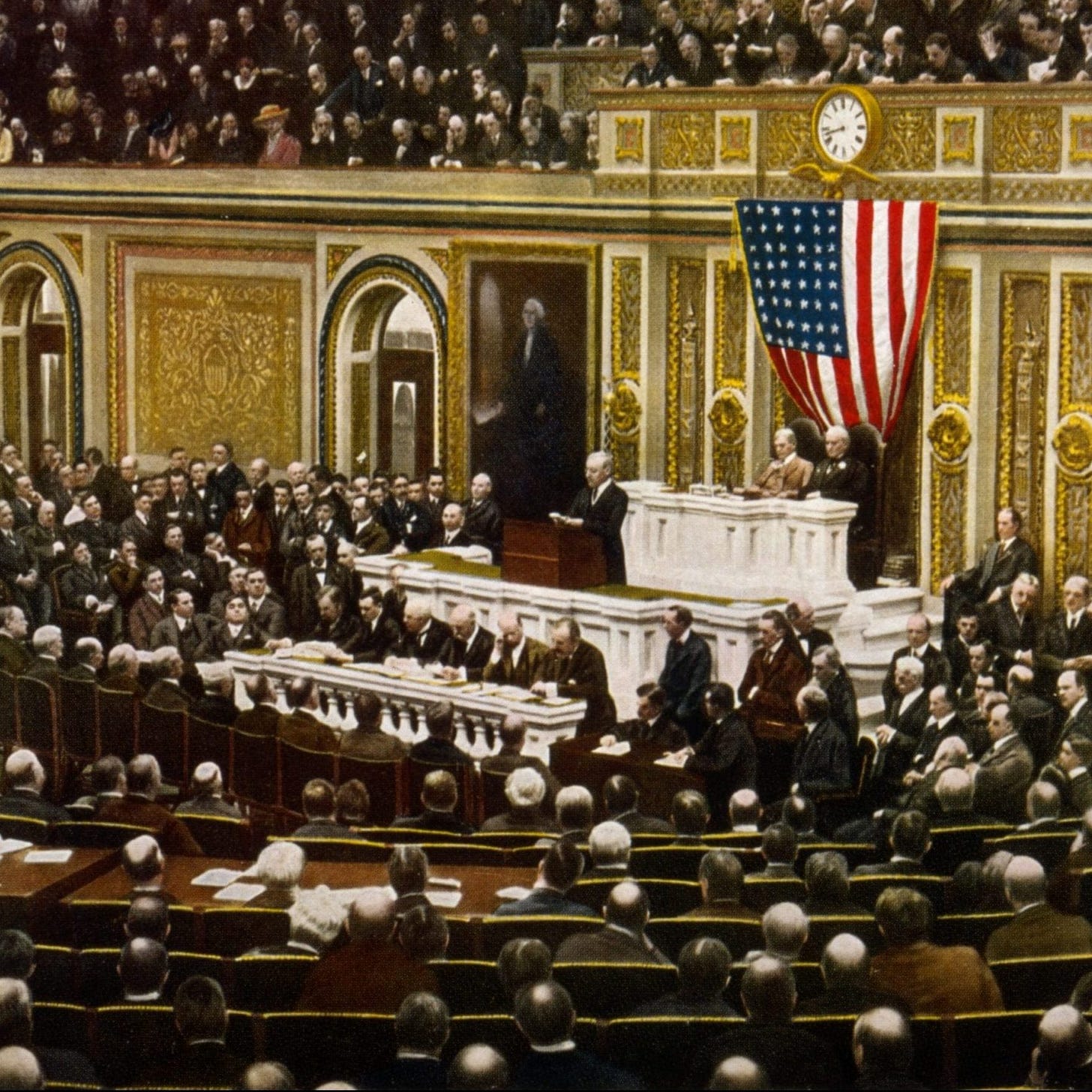

Thomas Brackett Reed (R Maine) was the Speaker that almost gave the Progressives what they wanted. He reformed the rules of the House to ensure the minority would no longer be able to block legislation, in fact they are still called Reed’s Rules. The Progressives thought he was in a position to coordinate government activity and fix, what they believed were the defects of the constitutional order. He controlled the committee assignments, he controlled the flow of business in the House and even controlled what bills made it to the floor through the committee assignments. One of Reed's biggest “reforms” was reducing the size the institution called The Committee of the Whole, which was the number of Representatives needed to conduct business. Reed changed it from a majority of the elected Representatives to only 100. The Speaker was also the chairman of the Committee on Rules, a five man committee, consisting of the Speaker, two other members of his party as well as two members from the minority. This body wielded significant power because they placed every bill on the legislative calendar, usually in chronological order with the most recent bills at the end. If there was a bill which the Speaker wanted immediate action on, he could call for a vote to place it at the front of the line and since there was only two minority members, the Speaker always won the vote. Reed eventually resigned over a dispute over the legitimacy of the Spanish-American War and was replaced by Joseph Gurney Cannon (R Illinois). Cannon was Speaker from 1903 until 1911 and probably more powerful than both presidents with whom he served; Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. He was, however, a conservative and anti-Progressive and used his power to stop most Progressive legislation. Cannon clashed with Progressive members of both parties and eventually there was an event called the Palace Revolt of 1910. The Republican party split into two factions; the Conservatives, who followed Cannon in his anti-Progressive outlook and the Insurgents who were led by George Norris (R Nebraska). On St. Patrick’s Day, while many of Cannon’s supporters in the House were out celebrating, Norris seized his opportunity to combine with Democrats to introduce a resolution reducing the Speaker’s powers. In particular, the Norris resolution sought to end the Speaker’s control over Congress’s legislative agenda by reducing his influence on the Committee on Rules. The debate raged throughout the night, and into the following afternoon, as members argued whether Norris’s resolution was privileged, and therefore at the top of the agenda, or whether the Speaker had to grant permission to even vote on the resolution. Ultimately, Cannon ruled that the resolution was not privileged; Norris appealed to the whole House, which overruled Cannon’s decision, and the resolution was passed, ending the era of “czar” Speakers. The results of this reform were mixed for Progressives. First, the party caucus and then an independent Rules Committee replaced the Speaker as the gatekeeper for all legislation in the House. So, instead of loosening the restrictions on passing legislation, the revolt simply transferred power from the Speaker to other institutions that filtered legislation in the House. From that point on, the Speaker of the House would never again have the powers that enabled him to represent the will of his party and push his party’s agenda through the House of Representatives. Committee chairs became “barons” of the House, no longer subject to the control of Speakers and the majorities they represented.

The first example of Congress delegating power was the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1887. It was created to dictate rates at which railroads could haul goods to markets in response to the pleas of farmers from Midwestern states. The ICC had limited power but that was soon to change. In 1906 Theodore Roosevelt used his “bully pulpit” to force Congress to pass the Hepburn Act, which dramatically expanded the ICC’s power to set railroad rates and regulate the railroads. After Woodrow Wilson’s victory in the 1912 presidential election, the wave of Progressive reform became a tsunami. The Federal Reserve Act, creating the Federal Reserve System, was passed late in 1913, and the Clayton Anti-Trust Act was passed in 1914, strengthening the antitrust powers held by the Federal Trade Commission, which had been created that same year. The FTC was empowered to eliminate “unfair competition,” an open-ended phrase defined, of course, by the FTC commissioners. These commissioners, furthermore, would be appointed by the President upon confirmation by the Senate, but they could not be removed by him except in extreme cases of wrongdoing or incompetence. The same was true of the commissioners of the ICC.

The Progressive Era as a movement ended around 1925, but its ideas persisted and the ideology gained adherents both among academics and politicians and government officials. As a body, Congress came to be more swayed by Progressive ideas once it was made up of a Democratic majority during the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt.

During the FDR administration Congress delegated even more power to entities outside of itself with the creation of the Food and Drug Administration in 1906, the Federal Radio Commission (precursor to the Federal Communications Commission) in 1927 and Federal Power Commission in 1930. These agencies had received broad delegations of authority from Congress, that gave them the power to make law, not simply execute it. The Federal Communications Act of 1934, for example, changed the name of the Federal Radio Commission to the Federal Communications Commission and directed it to grant broadcast licenses to applicants “if public convenience, interest, or necessity will be served thereby.” Additionally, the heads of these agencies would not be accountable to the President, which meant that they existed as a “fourth branch” of government, not directly accountable to any of the three constitutional branches. Roosevelt used his position as President to pressure Congress into passing the Social Security Act of 1935 which created the Social Security Administration, the Banking Act of 1933 which created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Securities Act of 1933 which created the Securities and Exchange Commission, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 which created the National Labor Relations Board and many others. Congress’ delegation of it’s power continued even after the death of Franklin Roosevelt.

Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society created just as many if not more administrative agencies to expand the bureaucracy such as the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 which created the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 which created the Office of Economic Opportunity and the Community Action Agencies, Clean Air Act of 1963, the Water Quality Act of 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and the Higher Education Act of 1965 which was the first time that the federal government became involved in public schools and higher education. Medicare and Medicaid were also created during this time with amendments to the Social Security Act. Quite a few social programs that allowed the government to insinuate itself into the daily life of Americans was also passed during this time, like the Food Stamp Act of 1964, and the the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 which created the School Breakfast Program. Meals on Wheels was created in 1965, and in 1967 the federal government began mandating that state health departments make contraceptives available to all low-income adults. Even Republican presidents got in on the act, with Richard Nixon signing both the Consumer Product Safety Act of 1972 which created the Consumer Product Safety Commission and the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 that created the Environmental Protection Agency.

As the Administrative State became bigger and bigger throughout history. The role of the Legislature became less and less important. During the debate on Obamacare, when Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi said “we have to pass it, to know what’s in it.” She wasn’t saying that she hadn’t read it, although I’m sure she had not, but that the specifics of the day to day operations under the bill would not be decided until the agency tasked with its enforcement, wrote those regulations. That is how far we have moved away from the original intent of the Framers.

I think this lays a solid groundwork for what has gone wrong in our system. It was hijacked by people who didn’t even believe in the basic tenants of the founding of our country. Next time I will examine the Executive and Judicial branches and their role in this mess. As always I hope you are getting some kind of pleasure out of reading these posts and please feel free to share them with anyone who might be interested. Until next week, You Stay Classy Substack!

Chris