I’m sitting here trying to figure out what to write, and nothing is coming to mind. At first I wanted to write about a Marine Corps thing called Force Design 2030, and I will eventually, but it is a very complicated topic that uses jargon that is even hard for me to understand. Besides, I just did a Marine Corps post and didn’t want to do another so soon. Should I do another post about things that are annoying me right now? I decided against that because right now I’m just not feeling energized enough to go on multiple rants about subjects that are in the news. I could do a post about how President Biden is an international embarrassment and cobble together all the clips of him doing weird things in public, but again I’m just not feeling it right now. So, I decided to fall back on an old standby, baseball. This time instead of complaining about baseball, I thought I would enter the “who’s the best” fray by listing my opinion of the best player at every position. My dad would say this is a stupid exercise because of the long history of baseball and the different playing styles throughout that history, but I just think it would be fun to revisit some old time players and since I was just at the Baseball Hall of Fame, I thought now is as good a time as any. I will list eleven players; two pitchers (a right hander and a lefty) and one player from each position, including a DH. Once again, this is my view of the best players not anyone else’s and opinions may differ. Here we go.

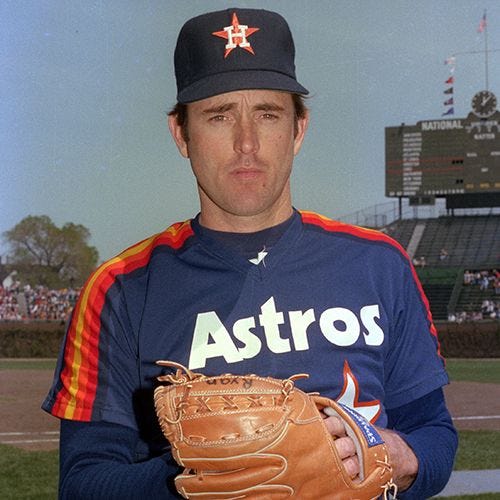

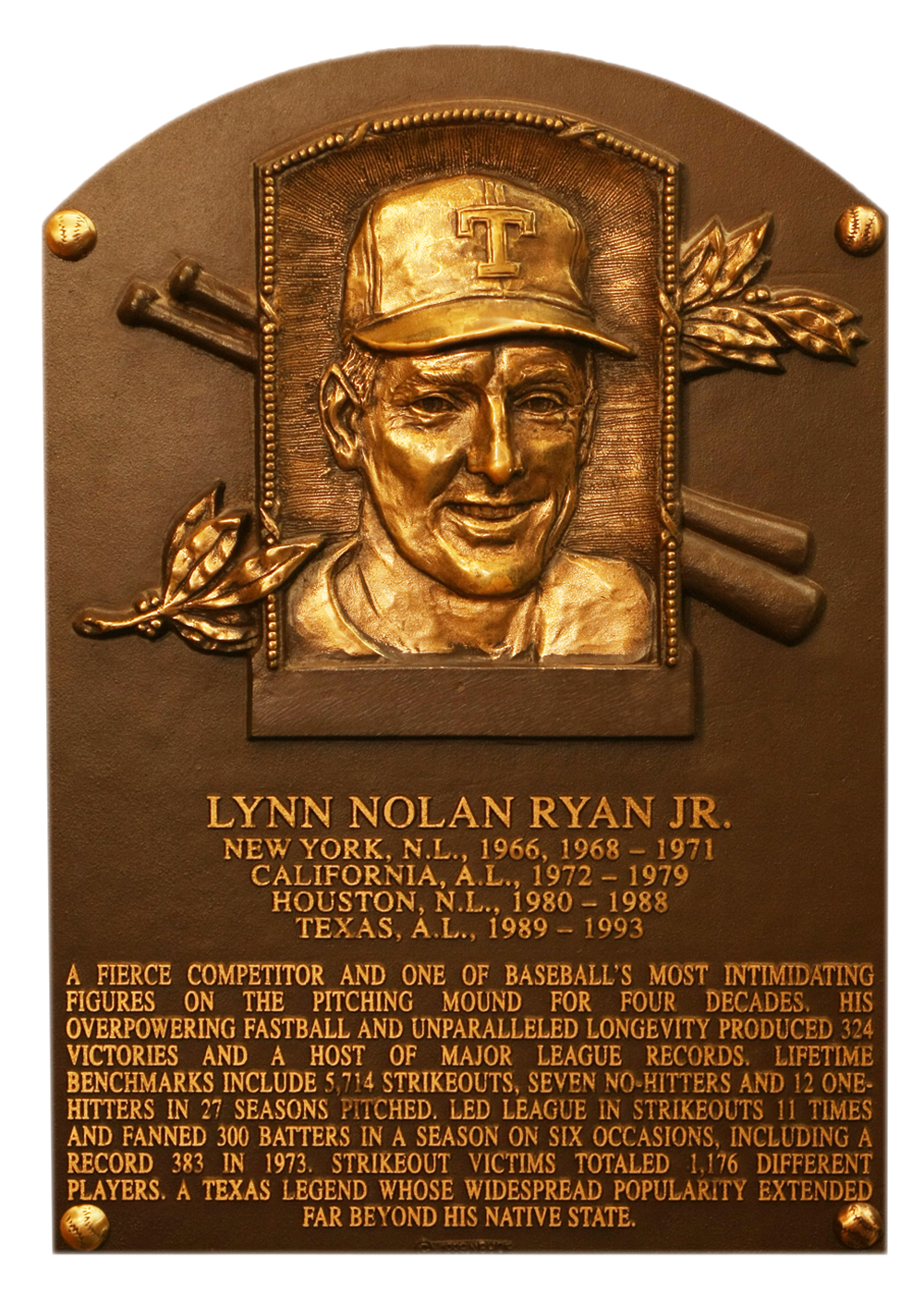

Right handed pitcher: Nolan Ryan

This is an easy choice, Ryan is the most dominate pitcher of all time. He was the first pitcher that was clocked on a radar gun throwing over 100 MPH but thanks to the scientific and mathematical analysis done in the documentary Fastball, we now know that his fastest pitch should have been recorded at 108.5 MPH! In his 27 year career from 1966 to 1993, with the Mets, Angels, Astros and Rangers, he was 324-292 for a winning percentage of .526 and this was while playing for some bad teams, in fact his teams only made the playoffs six times. He has a career ERA of 3.19 and led the Majors in ERA twice (1981 and 1987), walks eight times (1972, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1980 and 1982), strike outs eleven times (1972, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1987, 1988, 1989 and 1990). He has 222 complete games, to put that in perspective and give a little ammo to my dad’s argument, since 2016 there have been 269 complete games for every Major League team combined. He has 61 shutouts putting him 7th all time (only one of the other six pitched after 1930). He compiled 5,714 strikeouts 1st all time (second on the list is Randy Johnson who is 839 strikeouts behind. The current active leader in strikeouts in Max Scherzer with 3,294). Oddly, Ryan also leads baseball in walks with 2,795 but that doesn’t mean he was wild since he only hit an average of seven batters a season. He holds the record for the lowest batting average against him, with opposing hitters batting .207 when he pitched. He was a 8-time All-Star and also holds the record for the most no-hitters with seven, four more than any other pitcher. He also has the most one-hitters with 12 and the most two-hitters with 18.

Ryan was born in January 31, 1947 in Refugio, Texas but grew up in Alvin, Texas and played baseball at Alvin High School. Ryan set the school's single game strikeout record, striking out 21 hitters in a seven-inning game (which is ever hitter he faced that game). In 1963, at a game against Clear Creek High in League City, Texas, Red Murff, a scout for the New York Mets, first noticed the sophomore pitcher. In his subsequent report to the Mets, Murff stated that Ryan had "the best arm I've seen in my life." As a senior in 1965, Ryan had a 19–3 record and led the Alvin Yellow Jackets to the Texas high school state finals. Ryan pitched in 27 games, with 20 starts. He had 12 complete games, with 211 strikeouts and 61 walks. In 1965 MLB Draft (the first ever) the Mets drafted Ryan in the twelfth round, 226th overall. Ryan signed with the Mets and was sent to the Rookie League Marion Mets. In 1966 he was sent to the Class A, Greenville Mets where he was 17–2 with a 2.51 ERA and 272 strikeouts in 183 innings. He was promoted to the AA Williamsport Mets where he was 0–2 with a 0.95 ERA, striking out 35 batters in 19 innings. His performance earned him a late season call up to the Mets where he appeared in two games but did not fare well with an ERA of 15.00 in only three innings. Ryan missed much of the 1967 season due to illness, an arm injury, and service with the Army Reserve, pitching only eleven innings for the whole year. In 1968 he made the Mets major league roster out of training camp and would stay in the Majors until his retirement in 1993.

On December 10, 1971, the 24-year-old Ryan was traded to the California Angels along with pitcher Don Rose, catcher Francisco Estrada and outfielder Leroy Stanton for Jim Fergosi (who later managed Ryan with the Angels). The deal has been cited as one of the worst in Mets history, but was not viewed as unreasonable at the time given Ryan's relatively unremarkable numbers as a Met and Fregosi's good career to that point. On July 9, 1972, Ryan struck out three batters on nine pitches in the second inning of a 3–0 win over the Boston Red Sox, becoming the seventh American League pitcher to throw an immaculate inning, and the first pitcher in Major League history to accomplish the feat in both leagues (he had his first immaculate inning in 1968 wit the Mets). Ryan threw two no-hitters in 1973. In the second one, on July 15 against the Detroit Tigers, he struck out 17 batters – the most in a recorded no-hitter. Ryan was so dominant in this game, it led to one of baseball's best-remembered pranks. Tigers first baseman and cleanup hitter Norm Cash came to the plate with two outs in the bottom of the ninth, having already struck out twice, carrying a clubhouse table leg instead of a bat. Plate umpire Ron Luciano ordered Cash to go back and get a regulation bat, to which Cash replied, "Why? I won't hit him anyway!" With a regulation bat in hand, Cash did finally make contact, but popped out to end the game. Cash's teammate Mickey Stanley commented on facing Ryan that day by saying, "Those were the best pitches I ever heard." Ryan had another no-hitter in 1974 at home against the Twins walking eight and fanning 15. In 1975 again at home but against the Baltimore Orioles he had his fourth no-no strikoing out nine and walking four and tying Sandy Kofax for the record. He broke the record in 1981 while playing for the Houston Astros, when he no-hit the LA Dodgers, striking out eleven and walking three. He had his sixth no-hitter in 1991 against the Oakland A’s and his seventh against the Toronto Blue Jays in 1991 at the age of 44.

On a personal note, my favorite memory of Nolan Ryan was on August 4, 1993, in a game against the Chicago White Sox, when he hit Robin Ventura with a pitch in the back. Ventura charged the mound. Not one to back down from a fight, Ryan more than held his own against a player 20 years younger. He quickly put Ventura in a headlock and rained punches on the overmatched third baseman's head. This has to be one of the most lopsided fights in Major League history and you can watch it below.

Left handed pitcher: Warren Spahn

This is a controversial choice, with Randy Johnson, Sandy Kofax and Steve Carlton out there, but this is my list and I like him. I have a special connection to this gifted lefty. He was born in Buffalo, New York, the city I was born in, and when he was a kid he delivered newspapers with my Great Uncle. Warren Spahn had a 21 year career from 1942 to 1963 minus 1943, 1944 and 1945 when he served as a Combat Engineer and was awarded a Purple Heart and Bronze Star. He has a record of 363-245, a winning percentage of .597 and makes him the winningest left handed pitcher in Major League history. His career ERA is 3.09, he has 382 complete games and struck out 2,583 batters. He was a 14-time All-Star and the Cy Young Award winner in 1957 as well as the runner-up in 1958, 1960 and 1961. He led the National League in wins eight times (1949, 1950, 1953, 1957, 1958, 1959 and 1961), ERA three times (1947, 1953 and 1961), and strikeouts four times (1949, 1950, 1951 and 1952). He threw a no hitter in 1960 at the age of 39 and another the next year at 40. After his dominate performance in the 1948 playoff, the Boston Globe Sports Editor Gerald Herm wrote a poem about Spahn and his equally dominate teammate Johnny Sain.

First we'll use Spahn then we'll use Sain. Then an off day followed by rain. Back will come Spahn followed by Sain. And followed we hope, by two days of rain.

The poem was inspired by the performance of Spahn and Sain during the Braves' 1948 pennant drive. The team swept a Labor Day doubleheader, with Spahn throwing a complete 14-inning win in the opener, and Sain pitching a shutout in the second game. Following two off days, including a game lost to rain, Spahn won the next game, and Sain won the day after that. Three days later, Spahn won again and Sain won the next day. After one more off day, the two pitchers were brought back, and won another doubleheader. The two pitchers had gone 8–0 in 12 days' time.

As I said, Spahn grew up in Buffalo, New York were he attended Buffalo Bisons games with his father and initially wanted to be a first baseman. However, in 1935 when Spahn began to attend South Park High School, the first baseman position was already taken. Reluctantly, he took up pitching and led his high school team to two city championships, going undefeated his last two seasons, and throwing a no-hitter his senior year. He was signed by the Boston Braves after his senior year and sent to the Class D Bradford Bees. In 1941 he was assigned to the Class B Evansville Bees and in 1942 he pitched for the Class A Hartford Bees. In 1942 he made the Braves lineup out of spring training and there he stayed until 1966 and 1967 when he pitched in the Mexican League and AAA Tulsa.

On July 2, 1963, facing the San Francisco Giants, 42-year-old Spahn became locked into a storied pitchers' duel with 25-year-old Juan Marichal. The Giants manager Alvin Dark, visited Marichal on the mound in the 9th, 10th, 11th, 13th, and 14th innings, and was talked out of removing Marichal each time. During the 14th-inning visit, Marichal told Dark, "Do you see that man pitching for the other side? Do you know that man is 42 years old? I'm only 25. If that man is on the mound, nobody is going to take me out of here." The score was still 0–0 in the bottom of the 16th inning after more than four hours of baseball when, with one out, Willie Mays hit a game-winning solo home run off Spahn. Marichal ended up throwing 227 pitches in the win, while Spahn threw 201 in the loss. When asked about the homerun after the game, the always well-spoken Spahn said “Gentlemen, for the first 60 feet that was a great pitch!”

Catcher: Ivan Rodriguez

Another controversial choice with Johnny Bench, Mickey Cochrane and Mike Piazza out there. Pudge, played from 1991 to 2011, amassing 2,844 hits, 311 homeruns, 1332 RBIs and a career batting average of .296 and he stole 127 bases as a catcher making him 7th all-time on that list. He was one of the best defensive catchers ever. He won thirteen Gold Gloves and threw out 46% of all runners that attempted to steal against him, including the 2001 season when he threw out 60% of all runners. He was a 14-time All-Star and the American League MVP in 1999. He also won seven Silver Slugger Awards (created in 1980 and given to the best hitter at each position). For his career he hit better than .290 with more than 2,500 hits, 550 doubles, 300 home runs and 1,300 RBI, an accomplishment equaled only by four all-time greats: Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, George Brett and Barry Bonds. He also holds the record for most games played by a catcher and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2017 in his first year of eligibility.

Rodríguez was born on November 27, 1971 in Manati, Puerto Rico and grew up in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico. He learned baseball at an early age with his biggest rival on the Island being another future major leaguer, Juan Gonzalez. When he was eight, his dad, who was also his coach moved him from pitcher to catcher, because he was throwing so hard it was scaring the other kids. His favorite player growing up was Johnny Bench, even before he moved to catcher. He said that the Reds were always on TV in Puerto Pico and he saw how good Bench was. Rodríguez attended Lino Padron Rivera High School in Puerto Rico, where he was discovered by scout Luis Rosa. Rosa reported that "He showed leadership at 16 that I'd seen in few kids. He knew where he was going.” Rodríguez signed a contract with the Texas Rangers in July 1988, at the age of 16, and began his professional baseball career. Pudge made his professional debut in 1989 at the age of 17 as catcher for the Gastonia Rangers of the South Atlantic League. In his first game, he went 3-for-3 at the plate against Spartanburg. In 1990 he moved up to the Florida State League where he was given the award for Best Catcher and named to the All-Star team. That winter he played baseball in the Liga de Béisbol Profesional Roberto Clemente (a pro league in Puerto Rico) where he earned his nickname. According to Rodriguez:

“I got my nickname on the very first day of camp. Chino Cadahia, who was a Rangers coach at the time, gave me that name. He saw that I was short and stocky (5’9” 215 lbs.), so, from Day One, he started calling me "Pudge." It caught on, and the rest is history.”

At the beginning of the 1991 season, Rodriguez played 50 games with the Tulsa Drillers of the AA Texas League. After hitting .274 with three homeruns and 28 RBIs he was called up to the Majors, bypassing AAA. On June 20, 1991 he made his Major League debut and became the youngest catcher to play a MLB game at the tender age of 19.

First Base: Lou Gehrig

The original Iron Man, Gehrig held the record for consecutive games played with 2,130, for 56 years. Then, while still a great player, he was struck down with a disease that no one had heard of and for the longest time was called Lou Gehrig’s disease, ALS (Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Every baseball fan worth their salt remembers the speech he gave on July 4 1939, only four lines of the speech exist in recorded form:

Lou Gehrig played Major League Baseball for 17 years, from 1923 to 1939. In 2,164 games he amassed 2,721 hits, 493 homeruns, 1,995 RBIs and a career batting average of .340. He was the American League MVP twice and a seven time All-Star (the All-Star game wasn’t started until 1933). He won the Triple Crown (the best batting average, most homeruns and most RBIs in a season) in 1934 a feat that has only been accomplished seven times since. He is the only players to have at least 400 total bases in more than three seasons. He is one of two players to collect 500 doubles, 150 triples and 450 homeruns in a career, (Stan Musial is the other), he is one of four players (along with Babe Ruth Ted Williams and Stan Musial) to end their careers with at least a .330 batting average, 450 homeruns and 1,800 RBIs. He drew over 100 walks in a season eleven times. He scored the game winning run in eight World Series games and was the first athlete to appear on a box of Wheaties. Even though he is one of the greatest players of all-time, he was rarely the headliner in the papers, with teammate Babe Ruth garnering most headlines. Even on the day he became the first player to hit four homeruns in one game, the headlines the next day were about the retirement of New York Giants long-time manager John McGraw. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939 in a special election, waiving the normal five year waiting period.

Gehrig was born June 1903 in Manhattan, New York. He attended PS 132 in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, then went to Commerce High School were he first garnered national attention for his baseball ability while playing in a game at Cubs Park (now Wrigley Field) in Chicago. His team was playing Lane Tech High School in front of a crowd of more than 10,000 spectators. With his team leading 8–6 in the top of the ninth inning, Gehrig hit a grand slam completely out of the major league park, an unheard-of feat for a 17-year-old. After graduation he studied engineering at Columbia University and was the full back on the football team. On April 20, 1923, he was signed by the Yankees and left Columbia. He played 59 games in Class A Hartford before being called up to the Yankees where he hit .423 in 13 games. He spent most of the 1924 season in Hartford where he hit 37 homeruns before being called up again. This time he stuck and would play the rest of his career with the Yankees. Oddly enough, other than 193 games in Hartford he played his entire baseball life, sandlot, high school, college and pros, within a five square-mile area in New York City. He was a odd duck, which might have contributed to the lack of headlines. He lived with his parents until he was 30 and finally got married. His wife Eleanor took over for Gehrig’s mother as the driving force in Lou’s life. It was Eleanor that convinced the Iron Horse to hire Babe Ruth’s agent and it was the agent that got him on the Wheaties box. The agent, Christy Walsh, persuaded him to audition for the role of Tarzan in the independent film Tarzan’s Revenge. Gehrig only got as far as posing for a widely distributed, and embarrassing, photo of himself in a leopard-spotted costume. When Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs saw the photo, he sent a telegram to Gehrig reading, "I want to congratulate you on being a swell first baseman."

No one is sure when the ALS first started to manifest itself but by the second half of the 1938 season, Gehrig knew something was wrong. On May 2, 1939, before a game against the Detroit Tigers, Lou went to Yankees manager Joe McCarthy and told him he was taking himself out of the lineup “for the good of the team” (at the time he only had one RBI and was hitting .143). Before the game began, the announcer told the fans, "Ladies and gentlemen, this is the first time Lou Gehrig's name will not appear on the Yankee lineup in 2,130 consecutive games." The Detroit Tigers' fans gave Gehrig a standing ovation while he sat on the bench with tears in his eyes. He stayed with the Yankees as team captain for the rest of the season, but never played in a major-league game again. As Gehrig's debilitation became steadily worse, his wife, called the Mayo Clinic in Rochester Minnesota. She spoke with Charles Mayo, son of the founder, who had been following Gehrig's career and his mysterious loss of strength. Mayo told Eleanor to bring Gehrig as soon as possible. Gehrig flew alone to Rochester from Chicago, where the Yankees were playing at the time, and arrived at the Mayo Clinic on June 13. On June 19, 1939, after six days of extensive testing at the clinic, doctors diagnosed Gehrig with ALS, it was his 36th birthday. The prognosis was grim: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy less than three years, although no impairment of mental functions would occur. He would die on June 2, 1941 at his house in the Bronx. In 1949 American poet Ogden Nash wrote a poem for Sport Magazine called Line-up for Yesterday where he mentions a baseball player for every letter of the alphabet. Lou Gehrig represents G:

G is for Gehrig, The Pride of the Stadium; His record pure gold, His courage, pure radium.

Second Base: Rogers Hornsby

Rogers “Rajah” Hornsby played in the Majors for 23 years from 1915 to 1937. He played for the St. Louis Cardinals, St. Louis Browns, Boston Braves, Chicago Cubs and New York Giants. He played 2,259 games and racked up 2,930 hits, 301 homers, 1,584 RBIs and a career batting average of .358. He led the Majors in hits four times, (1920, 1921, 1922 and 1927), including a Major League record 227 hits in 1924. He was the National League MVP twice (1925 and 1929). He won the Triple Crown twice (1922 and 1925), was the National League batting champ seven times (1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925 and 1928), the National League homerun champ in 1922 and 1925 and the National League RBI champ four times (1920, 1921, 1922 and 1925). He is the only player to hit 40 homeruns and hit .400 in the same season (1922). His .424 batting average in 1922 is the highest in Major League history and he is tied with Ty Cobb with the most seasons hitting .400 or over with three. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1942 in his fifth year of eligibility. Rogers Hornsby was so respected as a hitter that once, when a rookie pitcher complained to umpire Bill Klem that he thought he had thrown Rogers a strike, Klem replied, "Son, when you pitch a strike, Mr. Hornsby will let you know." Hornsby never went to movies or read books, convinced that it would harm his eyesight, and he never smoked or drank. He was notoriously difficult to get along with, a major reason he changed teams so frequently in the last decade of his career.

Rajah was born on April 27, 1896 in Winters Texas but grew up in Fort Worth, Texas. He took a job with the Swift and Company meat packing plant as a messenger boy when he was 10, and he also served as a substitute infielder on its baseball team. By the age of 15, Hornsby was already playing for several semi-professional teams. He also played baseball for North Side High School until 10th grade, when he dropped out to take a full-time job at Swift. In 1914, Hornsby's older brother Everett, a minor League baseball player for many years, arranged for Rogers to get a tryout with the Dallas Steers of the Texas League. He made the team, but was released two weeks later without appearing in a game. He then signed with the Hugo Scouts of the Class D Texas-Oklahoma League as a shortstop for $75 per month ($2,191 today). The team folded a third of the way through the season, and Hornsby's contract was sold to the Denison Champions of the same league. In 1915 Denison changed its name to the Railroaders and joined the Western Association and raised Hornsby's salary to $90 per month ($2,603 today). At the end of the season a writer from The Sporting News said that Hornsby was one of about a dozen Western Association players to show any major league potential. Hornsby came to the attention of the St. Louis Cardinals during a series of exhibition games between the two teams during spring training in 1915. In September, the Cardinals purchased Hornsby's contract from Denison and added him to their major league roster and there he would stay until his last game in the Majors in 1937.

Rajah was also featured in Line-up for Yesterday, obviously representing H:

H is for Hornsby; When pitching to Rog, The pitcher would pitch, Then the pitcher would dodge.

Hornsby was also a Player-Manager throughout his career. In 1925 and 1926 with the Cardinals, 1927 with the Giants, 1928 with the Braves, 1930-1932 with the Cubs, and 1933 to 1937 with the Browns. Following his release from the Browns, Hornsby was unable to retire because he had lost so much money gambling over the years. He signed as a player-coach with the Baltimore Orioles of the International League in 1938 before leaving them to play for and manage the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern Association for the rest of the ‘38 season. Hornsby then returned to the Orioles in 1939. Halfway through 1940, he signed on to manage the Oklahoma Indians of the Texas League and led them from last place to the Texas League playoffs, where they fell to the Houston Buffaloes in four games. Hornsby began 1941 managing the Indians once again, but he resigned in the middle of the season. In November, he became the general manager and field manager of the Fort Worth Cats, also of the Texas league. Fort Worth finished in third place and made the playoffs in 1942, but they were eliminated in the first round and the league decided to suspend play for the duration of World War II. In February 1944, Hornsby signed as a player-manager with the Veracruz Blues of the Mexican League.

Hornsby actually won two games by inserting himself as a pinch hitter in the ninth inning, including one time where he drove in three runs with a bases-loaded double. His tenure in Mexico ended after only nine days, however, owing to financial differences with team owner Jorge Pasquel. Following his return to the United States, Hornsby spent 1945 out of baseball, his first campaign out of the game in over three decades. There were rumors that Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis had informally blackballed him from the majors because of his persistent gambling but he returned to manage the Browns in 1952 and the Cincinnati Reds from 1952 to 1953. The Browns players were so happy about Hornsby's firing that they gave team owner Bill Veeck an engraved trophy to thank him. He usually left due to falling out with the front office. As one contemporary writer put it, "Hornsby knew more about baseball and less about diplomacy than any player I knew." His lack of personality skills might have led to him being passed over four times for the Hall of Fame.

Third Base: Brooks Robinson

The Human Vacuum Cleaner, Mr. Hoover or Mr. Impossible, accurately describe Brooks Robinson, the greatest fielding third basemen of all time. He played 23 years in the Majors, from 1955 to 1977, for the Baltimore Orioles. In 2,896 games (2,870 at third base, a record for most games played at one position), he racked up 2,848 hits, 268 homeruns, 1,357 RBIs and a career batting average of .267. He has the highest fielding percentage of third basemen based on innings played with .971. He is a 18-time All-Star, the American League MVP in 1964, the World Series MVP in 1970. He sixteen Gold Gloves in a row, from 1960 to 1975. Those sixteen Gold Gloves are the most for any non-pitcher in history. He led the American League in RBIs in 1964. Upon his retirement during the 1977 season, Robinson's 2,896 career games and 10,654 at bats each ranked fifth in major league history and behind only Ty Cobb among AL players, and his 2,848 hits ranked seventh in AL history. From 1969 to 1980, he held the AL record for career home runs by a third baseman, (broken by Graig Nettles). He won the Roberto Clemente Award (given annually to the MLB player who best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual's contribution to his team) in 1972 and he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983 in his first year of eligibility

Robinson was born on May 1937 in Little Rock Arkansas, Brooks rooted for the St. Louis Cardinals and his favorite player was Stan Musial. He played American Legion baseball for the M. M. Eberts Post No. 1 Doughboys. The team reached the regional finals in 1952, when Robinson was 15 and advanced to the sectional tournament in 1953. Robinson who also played basketball graduated from Little Rock High School in 1955, earned a basketball scholarship to the University of Arkansas. However, Robinson wanted to become a professional baseball player. Lindsay Deal, who went to the same church as Robinson, had been a minor league teammate of Baltimore Orioles manager Paul Richards, wrote a letter to Richards praising Robinson's ability. "He's no speed demon, but neither is he a truck horse," Deal wrote. "Brooks has a lot of power, baseball savvy, and is always cool when the chips are down." Later in 1955, the New York Giants, Cincinnati Reds and Orioles all sent scouts to Arkansas to attempt to sign Robinson, each offering a $4,000 signing bonus. Robinson ultimately chose to sign with Baltimore because the Orioles had shown the most interest and had the most opportunities for young players to become everyday players on their roster. Robinson was sent to the York White Roses of the Piedmont League, he had late season call up where he played six games where he only hit .091. In 1956 he played for the San Antonio Missions of the Texas League. He got another call up that year and hit better, with a .227 in fifteen games before being sent back to San Antonio. In 1957 he made the major league roster but tore the cartilage in his right knee while avoiding a tag at first. After he recovered from his injury, he spent a month in San Antonio on a rehab assignment. Robinson competed for playing time with future Hall of Famer George Kell, though Kell happily mentored the younger player. Following the 1958 season, Robinson served six months in the Arkansas National Guard, which spared him the risk of being drafted and having to serve continuously for two years. The service kept him from being in optimal baseball shape, and shortly after the 1959 season started, Robinson was sent to the Vancouver Mounties of the AAA Pacific Coast League. He was recalled before the All-Star game and he played in the majors until his retirement in 1977.

In Ted Patterson’s book The Baltimore Orioles: Four Decades of Magic from 33rd Street to Camden Yards, he mentions that Robinson was very particular about his glove. He would try the gloves of different players and trade two of his own for theirs if he really wanted it. Once he found one he liked, he would take a year to prepare it. When he felt it was ready for game action, he would use it exclusively during games, using others for batting practice and infield workouts. He was also picky about his bat, though he would use different ones from game to game, sampling those of his teammates and even opposing players before he found one he wanted to utilize. Aside from his playing ability, Robinson endeared himself to the Orioles fans because of his personality. "Other stars had fans," goes a quote in Patterson's book. "Robby made friends." He treated them with patience and kindness while taking an interest in them as well. “When fans ask Brooks Robinson for his autograph,” commented Oriole broadcaster Chuck Thompson “he complied while finding out how many kids you have, what your dad does, where you live, how old you are, and if you have a dog. His only failing is that when the game ended, if Brooks belonged to its story – usually he did – you better leave the booth at the end of the eighth inning because by the time the press got to the clubhouse, Brooks was in the parking lot signing autographs on his way home." “Ted Patterson summed Robinson up this way “Never has a player meant more to a franchise and more to a city than Brooks has meant to the Orioles and the city of Baltimore,."

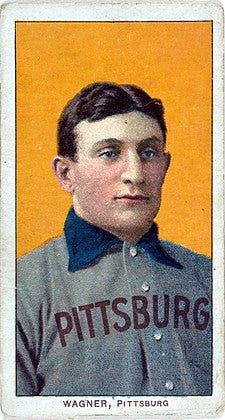

Shortstop: Honus Wagner

The Flying Dutchman Honus Wagner is a player that lives in the mists of time. He played for a Major League team that most people have never heard of, the Louisville Colonels. One one alive today even knows someone that saw him play. His 21 year career with the Louisville Colonels and Pittsburgh Pirates of the National League was over before World War I was over. In fact the American League didn’t even exist for the first four years of Wagner’s career. Honus played from 1897 to 1917 and in 2,794 games he amassed 3,420 hits, 101 homeruns, 1,732 RBIs, 723 stolen bases and a career batting average of .328. He led the majors in hits twice (1902 and 1906), doubles seven times (1900, 1902, 1904, 1906, 1907, 1908 and 1909), triples three times (1900, 1903 and 1908), RBIs four times (1901, 1902, 1908 and 1909), stolen bases four times (1901, 1902, 1907 and 1908), and batting average eight times (1900, 1903, 1904, 1906, 1907, 1908, 1909 and 1911). In 1899 he became the first player to steal second, third and home on consecutive pitches.

When the Baseball Hall of Fame held its first election in 1936, Wagner tied with Babe Ruth for second in the voting, trailing only Ty Cobb. Christy Mathewson, a Hall of Famer in his own right and also in that first class with Wagner, asserted that Wagner was the only player he faced who did not have a weakness. He felt that the only way to keep Wagner from hitting was not to pitch to him. Ty Cobb himself said Wagner was "maybe the greatest star ever to take the diamond". He is also the featured player of one of the rarest and the most valuable baseball cards in existence. The T206 card issued by the American Tobacco Company from 1909 to 1911, only 57 copies are known to exist. On August 3, 2022, a T206 was sold in a private sale for a record $7.25 million, eclipsing the previous high of $6.6 million.

Wagner was also honored in Line-up for Yesterday, representing W:

W is for Wagner, The bow-legged beauty; Short was closed to all traffic with Honus on duty.

Honus was born February 24, 1874 in Chartiers Borough, Pennsylvania. He dropped out of school at age 12 to help his father and brothers in the coal mines. In their free time, he and his brothers played sandlot baseball and developed their skills to such an extent that three of his brothers went on to become professionals as well. Honus' brother Albert "Butts" Wagner was considered the ballplayer of the family but in 1895 when his Interstate League team was in need of help, it was Albert that suggested Honus to his coach. Wagner played for five teams in that first year, in three different leagues over the course of 80 games. In 1896, Edward Barrow, from the Wheeling Nailers, the team Wagner was playing for at the time, decided to take Honus with him to his next team, the Paterson Silk Sox of the Atlantic League. Barrow proved to be a good talent scout, as Wagner could play wherever he was needed, including all three bases and the outfield. Wagner hit .313 for Paterson in 1896 and .375 in 74 games in 1897. Recognizing that Wagner should be playing at the highest level, Barrow contacted the Louisville Colonels who had finished last in the National League in 1896 with a record of 38–93. They were doing better in 1897 when Barrow persuaded club president Barney Dreyfuss, club secretary Harry Pulliam and Player/Manager Fred Clarke to see Wagner play. Dreyfuss and Clarke were not impressed with the awkward-looking man, not surprising, as Wagner was oddly built: he was 5 ft 11 in tall, weighed 200 pounds, had a barrel chest, massive shoulders, heavily muscled arms, huge hands, and incredibly bowed legs that deprived him of any grace and several inches of height. Pulliam, though, persuaded Dreyfuss and Clarke to take a chance on him. Wagner debuted with Louisville on July 19 and hit .338 in 61 games, beginning his illustrious career. Wagner was not finished playing after his retirement from Major League baseball. He managed and played for a semi-pro team and served the Pirates as a coach for 39 years, most notably as a hitting instructor from 1933 to 1952. His appearances at National League stadiums during his coaching years were always well received and Wagner remained a beloved ambassador of baseball. Wagner also coached baseball and basketball at Carnegie Institute of Technology, now now part of Carnegie Mellon University.

Left Field: Ted Williams

The Splendid Splinter or The Kid is the greatest hitter of the modern era of baseball and the last player to hit over .400 in a season. He played nineteen years for the Boston Red Sox, from 1939 to 1960 minus 1943, 1944, 1945, nearly all of 1952 and most 1953 when he served as a Marine Corps Aviator during both World War II and Korea. He was awarded three Air Medals and future astronaut, John Glenn called him one of the best pilots he knew and made Williams his wingman.

During his career he played 2,292 games getting 2,654 hits, 521 homers, 1829 RBIs and a batting average of .344. He was a 19-time All-Star, two-time AL MVP (1946 and 1949), two-time Triple Crown winner (1942 and 1947). He was a six-time AL batting champion (1941, 1942, 1947, 1948, 1957 and 1958), four-time AL homerun leader (1941, 1942, 1947 and 1949), four-time AL RBI leader (1939, 1942, 1947, 1949). He led the AL in runs scored six times (1940, 1941, 1942, 1946, 1947 and 1949), doubles twice (1948 and 1949), walks eight times (1941, 1942, 1946, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1951 and 1954), and his career On Base Percentage of .482 is a Major League record. He was a distracted fielder at the best of times, often practicing his swing in left field while the game was going on but the Red Sox were willing to live with that because of his superb hitting. Throughout his career, Williams stated his goal was to have people point to him and remark, "There goes Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived." Williams was an obsessive student of hitting. He famously used a lighter bat than most sluggers, because it generated a faster swing. In 1970, he wrote a book on the subject, The Science of Hitting (revised 1986), which is still read by many baseball players. The book describes his theory of swinging only at pitches that came into ideal areas of his strike zone, a strategy Williams credited with his success as a hitter. Pitchers apparently feared Williams; his bases-on-balls-to-plate-appearances ratio (.2065) is still the highest of any player in the Hall of Fame to which he was elected in 1966 in his first year of eligibility.

Williams was born in San Diego on August 30, 1918. At the age of eight, he was taught how to throw a baseball by his uncle, Saul Venzor, a former semi-pro baseball player who had pitched against Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in an exhibition game. He attended Herbert Hoover High School and although he had offers from the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees while he was still in high school, his mother thought he was too young to leave home, so he signed up with the local minor league club, the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League. Williams played back-up behind Vince DiMaggio and Ivey Shiver but when Shiver announced he was quitting to become a high school football coach in Georgia, the job was open for Williams, he posted a .271 average in 42 games for the Padres in 1936. Unknown to Williams, he had caught the eye of the Boston Red Sox's general manager, Eddie Collins, while Collins was scouting Bobby Doerr in August 1936. Collins later explained, "It wasn't hard to find Ted Williams. He stood out like a brown cow in a field of white cows." In the 1937 season, after graduating from Hoover High in the winter, the Padres ended up winning the PCL title and Williams hit .291 with 23 home runs. Meanwhile, Collins had kept in touch with Padres general manager Bill Lane, calling him throughout the season. In December 1937, during the winter meetings, a deal was made between Lane and Collins, sending Williams to the Red Sox and giving Lane $35,000 and two major leaguers, Dom D'Allessandro and Al Miemiec and two minor leaguers. In 1938, the 19-year-old Williams was 10 days late to spring training in Sarasota, Florida, because of flooding in California that blocked the railroads. When he finally arrived, Red Sox equipment manager Johnny Orlando told Collins "'The Kid' has arrived" and nickname stuck. He stayed with the Sox for a week and was then sent to the AA Minneapolis Millers of the Western League. While in the Millers training camp, Williams met Rogers Hornsby, who was a coach for the Millers and had hit over .400 three times, including a .424 average in 1924. Hornsby gave Williams useful advice, including how to "get a good pitch to hit". Talking with the game's greats would become a pattern for Williams, who also talked with Hugh Duffy, who hit .438 in 1894, Bill Terry, who hit .401 in 1930, and Ty Cobb with whom he had a long relationship and would argue about the proper swing path for a hitter. Williams thought a batter should swing upwards on the ball while Cobb’s view was that a hitter should hit down on the ball. Williams ended up hitting .366 with 46 home runs and 142 RBIs that season, winning the Western League Triple Crown and finishing second in MVP voting to Ollie Bejma (woops!). In 1939 Williams made the roster of the Red Sox and would play in the Majors until he retired.

Williams was temperamental, high-strung, and at times tactless and had a strained relationship with reporters and often the fans as well. He lost the MVP voting in 1947 by one vote because a reporter who didn’t like him left Williams off his ballot. On one hand Williams gave generously to those in need, especially the Jimmy fund of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which provides support for children's cancer research and treatment. Williams used his celebrity to virtually launch the fund, which raised more than $750 million between 1948 and 2010. Throughout his career, Williams made countless bedside visits to children being treated for cancer, which Williams insisted go unreported. Often parents of sick children would learn at check-out time that "Mr. Williams has taken care of your bill". The Fund recently stated that "Williams would travel everywhere and anywhere, no strings or paychecks attached, to support the cause. His name is synonymous with our battle against all forms of cancer." On the other hand Williams demanded loyalty from those around him. He could not forgive the fickle nature of the fans—booing a player for booting a ground ball, and then turning around and roaring approval of the same player for hitting a home run. Despite the cheers and adulation of most of his fans, the occasional boos directed at him in Fenway Park led Williams to stop tipping his cap in acknowledgment after a home run. Williams maintained this policy throughout his career, including his swan song in 1960. After hitting a home run at Fenway Park, in what would be his last career at-bat, Williams characteristically refused either to tip his cap as he circled the bases or to respond to prolonged cheers of "We want Ted!" from the crowd by making an appearance from the dugout. Boston manager Pinky Higgins sent Williams to left field to start the ninth inning, but then immediately recalled him for his backup Carroll Hardy, thus allowing Williams to receive one last ovation as he jogged onto then off the field, and he did so without reacting to the crowd. Williams's aloof attitude led the writer John Updike to observe wryly that "Gods do not answer letters."

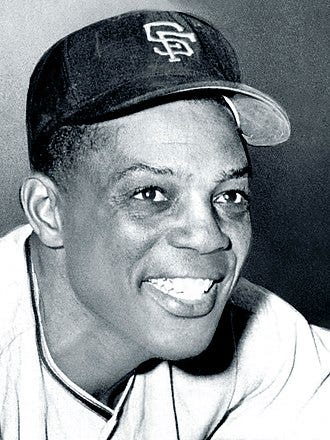

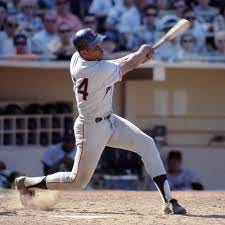

Center Field: Willie Mays

The Say Hey Kid, it could be argued, is the greatest ball player of all time. His combination of power and speed was unheard of before he burst on the scene in 1951. Mays played for the New York/San Francisco Giants and New York Mets in a 23 year career. From 1951 to 1973 minus 1953 when he was in the Army, he played in 3005 games amassing 3,293 hits (13th all time), 660 homers (6th all time), 1,909 RBIs (12th all time), and a batting average of .301. He was a twenty-time All-Star, two-time NL MVP, 1951 NL Rookie of the Year, twelve-time Gold Glove award winner, NL batting champion in 1954, and the Roberto Clemente Award winner in 1971. He led the National League in homeruns four times (1955, 1962, 1964, 1965) and stolen bases four times (1956, 1957, 1958 and 1959). He had the seventh four-homerun game in Major League history on April 30, 1961, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979 in his first year of eligibility.

Willie Howard Mays Jr. was born on May 6, 1931, in Westfield, Alabama, a primarily black company town near Fairfield, Alabama. His father, a talented baseball player on the black team at the local iron mill, exposed Willie to baseball at an early age, playing catch with him at five and allowing him to sit on the bench with his Birmingham Industrial League team at ten. His favorite baseball players growing up were Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams. Mays played football and basketball as well as baseball at Fairfield Industrial High School. Mays's professional baseball career began in 1948 when he played briefly during the summer with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos, a black minor league team. Later that year, Mays joined the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League managed by Piper Davis, a teammate of Mays' father on the iron mill team. When his high school principal threatened to suspend Mays for playing professional ball, Davis and Mays' father worked out an agreement that he would only play home games for the Black Barons, and in return he could still play high school football. Mays helped Birmingham advance to the 1948 Negro World Series, losing to the Homestead Grays four games to one. Mays only hit .262 for the season but stood out because of his excellent fielding and base running. Several major league teams were interested in signing Mays, but they had to wait until he graduated from high school to offer him a contract. After graduation he signed with the New York Giants for $4,000. Mays spent the rest of 1950 with the Class B Trenton Giants of the Interstate League and hit .353 for the season, before being promoted to the AAA Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. After playing well in Minneapolis, Mays was called up to the Giants on May 24, 1951, he was reluctant to accept the promotion because he did not believe he was ready to face major league pitchers. Stunned, Giants manager Leo “The Lip” Durocher called Mays personally and said, "Quit costing the ball club money with long-distance phone calls and join the team." The Giants hoped Mays would help them defensively in center field, as well as offensively. The Giants played in a stadium called the Polo Grounds which featured an unusual horseshoe shape. It had a short fence in left (280 feet) and right( 258) but had the deepest centerfield in baseball history at 483 feet, which put tremendous pressure on the centerfielder to cover a lot of ground. Mays appeared in his first major league game on May 25 against the Philadelphia Phillies at Shibe Park, batting third. He had no hits in his first 12 at bats in the major leagues, but in his 13th on May 28, he hit a home run off Warren Spahn over the left field roof of the Polo Grounds, (the always loquacious Spahn told reporters that he thought that Mays was going to hit a lot of homers before his career was over). Mays went hitless in his next 12 at bats, and Durocher dropped him to eighth in the batting order on June 2, suggesting that Mays stop trying to pull the ball and just make contact. He would then go on a tear and finish the season with a .274 average, 68 RBI and 20 home runs and win the Rookie of the Year in the National League.

Defensively, Mays was one of the best outfielders of all time, as evidenced by his record 12 Gold Gloves. His signature play was his "basket catch," the technique that displayed Mays's stylistic flash as opposed to the pure raw skill that was on display when he made "The Catch" in the 1954 World Series.

Holding his glove around his belly, he would keep his palm turned up, enabling the ball to fall right into his glove. Sportswriters have argued about whether the technique made him a better fielder or just made him more exciting to watch, but the basket catch did not prevent Mays from setting a record with 7,095 outfield putouts. While the Giants were in New York there were endless debates on playgrounds, in diners, boardrooms and anywhere else baseball fans in New York gathered, about which of the three New York center fielders was the best; Willie, Mickey or the Duke (referring to Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle of the Yankees and Duke Snider of the Brooklyn Dodgers). Mays was also a popular figure in Harlem, home of the Polo Grounds. Magazine photographers were fond of chronicling his participation in local stickball games with kids, which he played two to three nights a week during homestands until his marriage in 1956. Mays could hit a shot that measured "six sewers" (the distance of six consecutive New York City manhole covers), nearly 450 feet. When Mays was elected to the Hall of Fame, he only garnered 409 of the 432 ballots cast (94.68%), causing the acerbic New York Daily News columnist Dick Young to quip "If Jesus Christ were to show up with his old baseball glove, some guys wouldn't vote for him. He dropped the cross three times, didn't he?

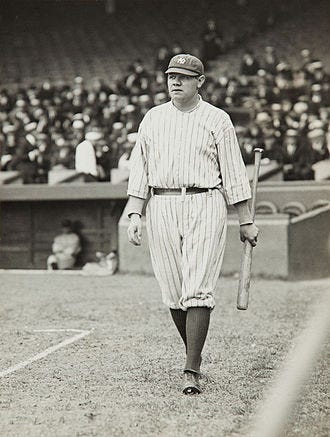

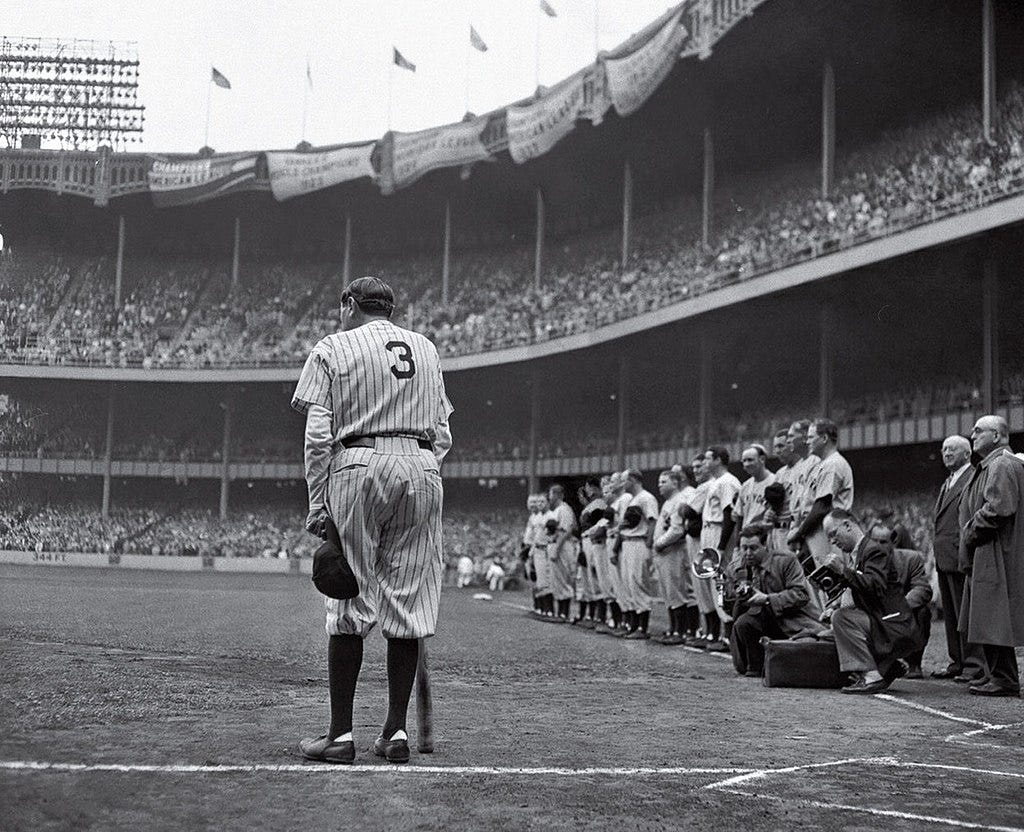

Right Field: Babe Ruth

The Great Bambino, The Sultan of Swat, The Prince of Pounders, The Wizard of Whack, The Behemoth of Bust, The King of Swing, The Titan of Terror, The King of Crash, The Colossus of Clout, The Mauling Menace, Jidge or Babe, whatever nickname you want to call him we all know who were talking about, George Herman Ruth, the greatest sports hero of all time and one of the best baseball players ever. Ruth was the first baseball star to be the subject of overwhelming public adulation. The US had seen stars of baseball like Ty Cobb and "Shoeless Joe" Jackson, but both men had uneasy relations with fans. At the time of Ruth’s emergence onto the public stage, the country had been hit hard by World War I and the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic and longed for something to help put those traumas behind it. Ruth also represented a country which felt, in the aftermath of the war, that it took second place to no one. Ruth was a larger-than-life figure who was capable of unprecedented athletic feats in the nation's largest city. In his history of the Yankees, Glenn Stout writes that "Ruth was New York incarnate—uncouth and raw, flamboyant and flashy, oversized, out of scale, and absolutely unstoppable". He played Major League baseball for 22 years for the Boston Red Sox, New York Yankees and Boston Braves from 1914 to 1935. In the early part of his career he was a pitcher, and only hit when he was pitching, but he made the move to full-time player in 1919. In 2,503 games he had 2,873 hits, 714 homeruns, 2,214 RBIs and a batting average of .342. He was the league MVP once (1923), two-time All-Star, AL Batting Champion once ( 1924), twelve-time MLB homerun leader (1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1923, 1924, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930 and 1931), five-time MLB RBI leader (1919, 1920, 1921, 1923 and 1926), eight-time MLB runs scored leader (1919, 1920, 1921, 1923, 1924, 1926, 1927 and 1928), his career slugging percentage of .690 is a Major League all-time record, and in 1916 he led the AL in ERA (earned run average, a measure of a pitcher’s effectiveness). He was also tied for the second-most votes for the inaugural class of the Baseball Hall of Fame with Honus Wagner, trailing only Ty Cobb. Ruth was also honored in A Lineup for Yesterday, obviously as the letter R:

R is for Ruth. To tell you the truth, There's just no more to be said, Just R is for Ruth.

George Herman Ruth Jr. was born on February 6, 1895 in the Pigtown section of Baltimore, Maryland. Many details of Ruth's childhood are unknown, details are equally scanty about why, at the age of seven Ruth was sent to the St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, a reformatory and orphanage. However, according to Julia Ruth Stevens' (Babe’s daughter) account in 1999, because George Sr. was a saloon owner in Baltimore and had given Ruth little supervision growing up, he became a delinquent. Ruth entered St. Mary's on June 13, 1902, he was recorded as "incorrigible" and spent much of the next 12 years there. Although St. Mary's boys received an education, students were also expected to learn work skills and help operate the school, particularly once the boys turned 12. Ruth became a shirtmaker and was also proficient as a carpenter. On his first day at St. Mary’s, he was told to join a sports team, by the school's athletic director, Brother Herman, he chose baseball and became a catcher. He was encouraged in his pursuits by the school's Prefect of Discipline, Brother Matthias Boutlier. A large man, Brother Matthias was greatly respected by the boys both for his strength and for his fairness. For the rest of his life, Ruth would praise Brother Matthias, and his running and hitting styles closely resembled his teacher's. Most of the boys at St. Mary's played baseball in organized leagues at different levels of proficiency. Ruth later estimated that he played 200 games a year as he steadily climbed the ladder of success. Although he played all positions at one time or another, he gained stardom as a pitcher. According to Brother Matthias, one day, Ruth was standing to one side laughing at the bumbling pitching efforts of fellow students, and Matthias told him to go in and see if he could do better. Ruth had become the best pitcher at St. Mary's, and in 1913 when he was 18, he was allowed to leave the premises to play weekend games on teams that were drawn from the community. He was mentioned in several newspaper articles, for both his pitching prowess and ability to hit long homers.

In early 1914, Ruth signed a professional baseball contract with Jack Dunn, the owner of the minor league, Baltimore Orioles, a team in the International League. The circumstances of Ruth's signing are not known with certainty. By some accounts, Dunn was urged to attend a game between an all-star team from St. Mary's and one from another boys home, Mount St. Mary’s College. Other versions have Ruth running away before the eagerly awaited game, return in time to be punished, and then pitching St. Mary's to victory as Dunn watched. Ruth, in his autobiography, stated only that he worked out for Dunn for a half hour, and was signed. Babe’s first professional appearance was in an exhibition game versus the Philadelphia Phillies. Ruth pitched the middle three innings and gave up two runs in the fourth, but then settled down and pitched a scoreless fifth and sixth innings. The next afternoon, Ruth entered another game against the Phillies during the sixth inning and did not allow a run the rest of the way. When the Orioles scored seven runs in the bottom of the eighth inning to overcome a 6–0 deficit, Ruth was the winning pitcher. Once the regular season began, Ruth was a star pitcher who was also dangerous at the plate. The team performed well, yet received almost no attention from the Baltimore press because a third major league, the Federal League had begun play, and the local franchise, the Baltimore Terrapins, the first Major League team in the city since 1902 were taking all the press coverage. Few fans visited Oriole Park where Ruth and his teammates labored in relative obscurity. Ruth may have been offered a bonus and a larger salary to jump to the Terrapins but when rumors to that effect swept Baltimore a Terrapins official denied it, stating it was their policy not to sign players under contract to Dunn. The competition from the Terrapins caused Dunn to sustain large losses. Although by late June the Orioles were in first place, having won over two-thirds of their games, the paid attendance dropped as low as 150. Dunn explored a possible move by the Orioles to Richmond, Virginia, as well as the sale of a minority interest in the club, however these possibilities fell through, leaving Dunn with little choice other than to sell his best players to major league teams to raise money. He offered Ruth to the reigning World Series champions, Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s, but Mack had his own financial problems. The Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants expressed interest in Ruth, but Dunn sold his contract, along with two other pitchers to the Boston Red Sox on July 4 1914. The announced price was $25,000. Ruth remained with the Orioles for several days while the Red Sox completed a road trip, and reported to the team in Boston on July 11. In his major league debut as a batter, Ruth went 0-for-2 against left-hander Willie Mitchell, striking out in his first at bat before being removed for a pinch hitter in the seventh inning. Ruth was not much noticed by the fans, as Bostonians watched the Red Sox's crosstown rivals, the Braves, begin a legendary comeback, that would take them from last place on July 4th to the 1914 World Series championship. After a season in which he was little used, Ruth was sent to the minors, playing for the Providence Greys. Ruth joined the Grays on August 18, 1914. Ruth was deeply impressed by Providence manager “Wild Bill” Donovan, a star pitcher with the Detroit Tigers, winning 25 games in 1907. He credited Donovan with teaching him much about pitching. Ruth was often called upon to pitch, in one stretch starting (and winning) four games in eight days. On September 5 at Maple Leaf Park in Toronto, Ruth pitched a one-hit 9–0 victory, and hit his first professional home run, his only one as a minor leaguer. After the Providence season was over, the Red Sox recalled Ruth and he never played in the minors again.

Babe Ruth’s impact on the game is nearly incalculable as is his impact on American culture, his penchant for hitting home runs altered how baseball is played. Prior to 1920, home runs were unusual, and managers tried to win games by getting a runner on base and bringing him around to score through such means as the stolen base, the bunt, and hit and run. What today is called “Small Ball” was dubbed “Inside Baseball” back then and advocates of it, like Giants manager John McGraw, disliked the home run, considering it a blot on the purity of the game. However, according to sportswriter W. A. Phelon, after the 1920 season, Ruth's breakout performance that season and the response in excitement and attendance, "settled, for all time to come, that the American public is nuttier over the Home Run than the Clever Fielding or the Hitless Pitching. Viva el Home Run and two times viva Babe Ruth, exponent of the home run, and overshadowing star." When the owners discovered that the fans liked to see home runs, and when the foundations of the games were simultaneously imperiled by disgrace (the 1919 Black Sox scandal, where eight player on the Chicago White Sox threw the World Series), then there was no turning back. While a few, such as McGraw and Ty Cobb, decried the passing of the old-style play, teams quickly began to seek and develop sluggers. In 1930 when he demanded the Yankees pay him $80,000 a year, more then the President of the United States at the time (Herbert Hoover), Ruth said that he had, had a better year! During World War II Japanese soldiers yelled in English, "To hell with Babe Ruth", to anger American soldiers. Ruth replied that he hoped "every Jap that mentioned my name gets shot. He transcended sport and moved far beyond the artificial limits of baselines, outfield fences and sports pages. In 2018, when President Donald Trump awarded a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom to Babe Ruth he said;

The fascination with his life and career continues. He is a bombastic, sloppy hero from our bombastic, sloppy history, origins undetermined, a folk tale of American success. His moon face is as recognizable today as it was when he stared out at Tom Zachary on a certain September afternoon in 1927. If sport has become the national religion, Babe Ruth is the patron saint. He stands at the heart of the game he played, the promise of a warm summer night, a bag of peanuts, and a beer. And just maybe, the longest ball hit out of the park.

Designated Hitter: Stan Musial

I know, there wasn’t designated hitters in Musial’s era but he needs to be on this list and I’m not leaving off Hank Aaron, Ted Williams or Lou Gehrig, so this is where he’s going. Stan “The Man” Musial played Major League baseball for 22 years from 1941 until 1963 minus 1945, when he was in the Navy. In 3,026 games he amassed 3,630 hits, 475 homers, 1951 RBIs and a career batting average of .331. He led all of baseball in hits six times, doubles eight times, triples five times, RBIs twice and batting average seven times. He was a twenty-time All-Star and the National League MVP three times, in 1943, 1946 and 1948. In fact he only finished lower than tenth in MVP voting three times in his 22 years.

Musial was born in Donora Pennsylvania on November 21, 1920. Young Stan frequently played baseball with his brother Ed and other friends during his childhood, and considered Lefty Grove his favorite ballplayer. He started playing semi-pro baseball in 1935 at the age of 15 with his home town Donora Zincs as well as his high school team, where one of his teammates was Buddy Griffey, father of Ken Griffey Sr. and grandfather of Hall of Famer, Ken Griffey Jr.). In 1937 the St. Louis Cardinals, who had scouted Musial with the Zincs, offered him a professional contract as a pitcher, after a workout with their Class D Penn State League team. He was a great all-around athlete, earning a basketball scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania but opting for baseball instead. In what was then a common practice, the Cardinals did not file the contract with the Office of the Baseball Commissioner, until June 1938. This preserved Musial's amateur eligibility, allowing him to keep playing high school sports and leading Donora High’s basketball team to a playoff appearance. After his senior year was over, Musial reported to the Cardinals' Class D affiliate in West Virginia, the Williamson Red Birds. By 1940, he had moved over to the Class D Florida League and the Daytona Beach Islanders, where his coach Dickie Kerr recognized his hitting abilities and would play him in the outfield between starts. He injured his shoulder diving for a ball there and he was never the same pitcher after that. Kerr made moved Musial to the outfield full time and in 1941 he made his Major League debut and the rest is history. On September 17, 1941, Musial made his major league debut during the second game of a doubleheader at Sportsman’s Park and with the Cardinals in a tight pennant race with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Musial collected 20 hits in twelve games. Despite Musial’s efforts the Cards ended the season 2-1/2 games behind the Dodgers.

Stan Musial played baseball the right way. Few who saw the Cardinals’ legend in person thought a better ballplayer existed. More than half a century after his retirement, Musial remains the face of a Cardinals’ franchise he helped turn into a dynasty. In a 1952 article in Life Magazine Ty Cobb said:

"No man has ever been a perfect ballplayer. Stan Musial, however, is the closest to being perfect in the game today. He plays as hard when his club is away out in front of a game as he does when they're just a run or two behind."

He is so beloved in St. Louis, that the city staged a lobbying effort to get Musial the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the US. He was awarded the medal in February 15, 2011. When Albert Pujols, arrived in St. Louis, he insisted that he no longer be called by the nickname El Hombre (Spanish for The Man) that he had, had since high school because there was only one “The Man” in St. Louis and it is Musial.

There is my list, please feel free to argue amongst yourselves and with me over the content of this list. If you think I should have put Roger Clemens in place of Nolan Ryan, or Mickey Mantle instead of Willie Mays or Johnny Bench in place of Pudge, let me know. This is meant to start conversations and remind everyone how great the game of baseball is. I hope you enjoyed this post and please share it with everyone you can. Sorry about it being a day late, I’ve been working a ton and just couldn’t get it finished on time. Until next time, have a great week.

Chris