Everything I Need To Know, I Learned In The Marine Corps.

Take care of your Marines first.

It is standard Marine operating procedure for officers and senior enlisted Marines to make sure their Marines have everything they need, food, water, shelter, whatever it was, before getting it themselves. In other words make sure your Marines are fed, watered and put up for the night before you do any of those things. An leader who doesn't follow this rule will lose the respect of his Marines and when that happens, unit cohesion goes right out the window and if that happens in a combat situation Marines could die. Even me, as a lowly Lance Corporal followed that maxim. In Somalia I was attached to a forward observer team as their radio operator. The other two Marines were 19 year old kids right out of FO school. I, on the other hand was a grizzled Gulf War veteran of 24 years with three years in the Marines. While I was with that team I made sure that they ate first, washed first, got water first and slept first.

NEVER volunteer for anything Ever!

You learn very quickly in the Marines and the Armed Forces in general, that when leaders ask for volunteers it is NEVER something fun and usually something dirty and hard and you should never volunteer. I volunteered once before I learned that rule, during boot camp in San Diego and I ended up unloading a semi filled with food for the chow hall. A hot, dirty and physical job especially after morning PT and before evening PT. I never volunteered for anything again. That doesn’t mean I did get assigned bad duties, it just meant I could grumble the whole time about being assigned that crappy duty.

Never leave a Marine behind.

The Marines take this one to a sometimes unbelievable level but it is essential for unit moral and cohesion. Every Marine needs to know that if something happens to them, their buddies will make every effort to come and get them whether you got lost on a training mission or are wounded near an enemy positions. There have even been occasions that units have taken additional causalities to retrieve dead Marines but the sentiment is the same.

My unit was sent to the Philippines because of a communist terrorist group called the NPA (New People’s Army) was killing American service men on the streets around Clark Air Force Base and Subic Bay Naval base. Because of this threat, we had what was known as Cinderella liberty. We could be off base from 7 am until midnight. At midnight they locked the gates and no one was allowed in or out until 7 am. One day a sergeant who had “befriended” a local young lady, fell asleep at her house and missed the midnight curfew. The next day when he wasn’t at formation, the battalion put on an all-hands search & rescue mission to find him, thinking he might have been a victim of the NPA. Unfortunately for him, when he was found and the reason for his absence was known he got in big, big trouble. He was reduced in rank from sergeant (E-5) to Private (E-1) and had to forfeit 2/3 of his pay for six months. It is just another example of never leave a Marine behind, even if it doesn’t turn out good for him.

Leave every place you go, cleaner than it was when you got there.

The Marines have taken the Boy Scout maxim “Take nothing and leave only footprints” to new levels. For the Marines it’s more like “Take nothing and leave it better than you found it”. My time in Somalia was a great example of this. When I arrived in early December 1992 the American and coalition forces and the UN contingent were still getting settled in but one of their first acts was to go on a huge cleaning spree across the country. Mogadishu’s airport and port facilities were first on the list, with junk that had accumulated over the last few years taken away to make room for follow-on forces and ship traffic. Building damaged by fighting were fully demolished and the lots cleared. Potholes in the streets, some big enough to swallow a humvee were filled in and every unit in country was told to spruce up the area around their camps. The country was sill a dangerous place with little to no basic services, like sanitation or medical services (other than those provided by the coalition, the UN or aid agencies) but it least it looked a little nicer.

Before long, and this connects with the next thing I learned, we were doing local police work, catching shoplifters and other petty criminals because the Somali police which had disappeared after the fall of the government hadn't been re-formed yet and even if than been, the population wasn't going to trust them for a while, because they had been agents of the deposed dictator. When I left Somalia in late March of 1993, it might not have been a safer place but it was certainly a cleaner place than it had been. Of course, it didn't stay clean and it got much more dangerous, but that's a different story.

Never trust politicians.

I'm sure most Americans love their politicians and know that they are only lying if their mouths are moving, but of course their mouths are always moving. Politicians are especially dangerous to the military. They have strange ideas, like every country in the world wants to be like the US and we need to “help” them even if they don’t want or need our “help”, or that we should be the policemen for the world and fix every injustice we see. An example would be Operation Restore Hope in Somalia.

I was sent to Somalia because the after the overthrow of the long-time dictator Siad Barre, the government of Somalia had collapsed, plunging the country into clan warfare. A symptom of that conflict saw one clan preventing food deliveries through their territory to other clans in the country's interior. The lack of food caused a famine, which killed 100 people a day. Soon the press got a hold of the story and put pressure on President George H. W. Bush and the United Nations to “do something”. The result of this was UNOSOM I and II (United Nations Operations in Somalia) and the Unified Task Force (UNITAF) a coalition of 24 nations. In the us it was called Operation Restore Hope. The orders were to secure food deliveries into the interior and assist relief efforts in the affected areas. The clan leaders, who were essentially warlords with their own private armies of young Somali men, welcomed the international forces and assisted efforts in moving the food to the interior while at the same time always blaming the other warlords for the problem. Eventually the food was getting to where it needed to be and relief efforts were moving along. Then someone, somewhere decided that Somalia couldn’t be left in it’s current state and that since we were there anyway we should just fix it. It started as orders to confiscate the plethora of local firearms, which we did by setting up roadblocks and searching cars. Then we were tasked with “assisting” local law enforcement and we were all given arrest powers and zip tie handcuffs. If we witnessed a crime we were authorized to arrest the induvial and detain them. The weapon confiscation program and the police powers did not sit well with the locals and their outlook towards us changed from a welcoming one to one where they view us as occupiers. Incidents of violence directed at UN and coalition forces started to increase and the activity of the warlords also started to trend upwards. Eventually it was decided in Washington that the main warlords, General Mohamed Farrah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Muhammad, needed to be dealt with. The UNITAF quickly came to an agreement with Ali Mahdi but Aidid was not willing to agree to anything with UNITAF. Eventually a raid to capture Aidid was planned. That operation was a failure, known as the Battle of Mogadishu, which was shown in the movie Blackhawk Down.

The military calls what happened in Somalia “mission creep” and it was not because of decisions made on the ground by military commanders. Those decisions were made by career “diplomats” and civil servants that are not accountable to the voters and tend to view themselves as the “experts” in whatever field they’re in. It is a hazard of the current bureaucracy that we live and one what we need to watch closely.

Five minutes early is ten minutes late.

This is what I was always told in the Marines and it has served me well in the civilian world. Of course in the Marines I would get wherever I need to be 15 minutes early and invariably whatever I was there to do would not start on time so the other phrase you heard was “hurry up and wait”. Everything is always a rush and then you just sit around waiting for something to happen. You hurry up to get to the chow hall in the morning and it doesn’t open on time. You hurry to get in formation and then the First Sargent is late. You hurry to get your gear together to leave the field and then the trucks are late. In fact it seems like the only person that is held to the 15 minute timeline is you, but such is life in the Marines.

Pack light but pack thoroughly because there’s nothing better than a clean pair of underwear, except a dry pair of socks.

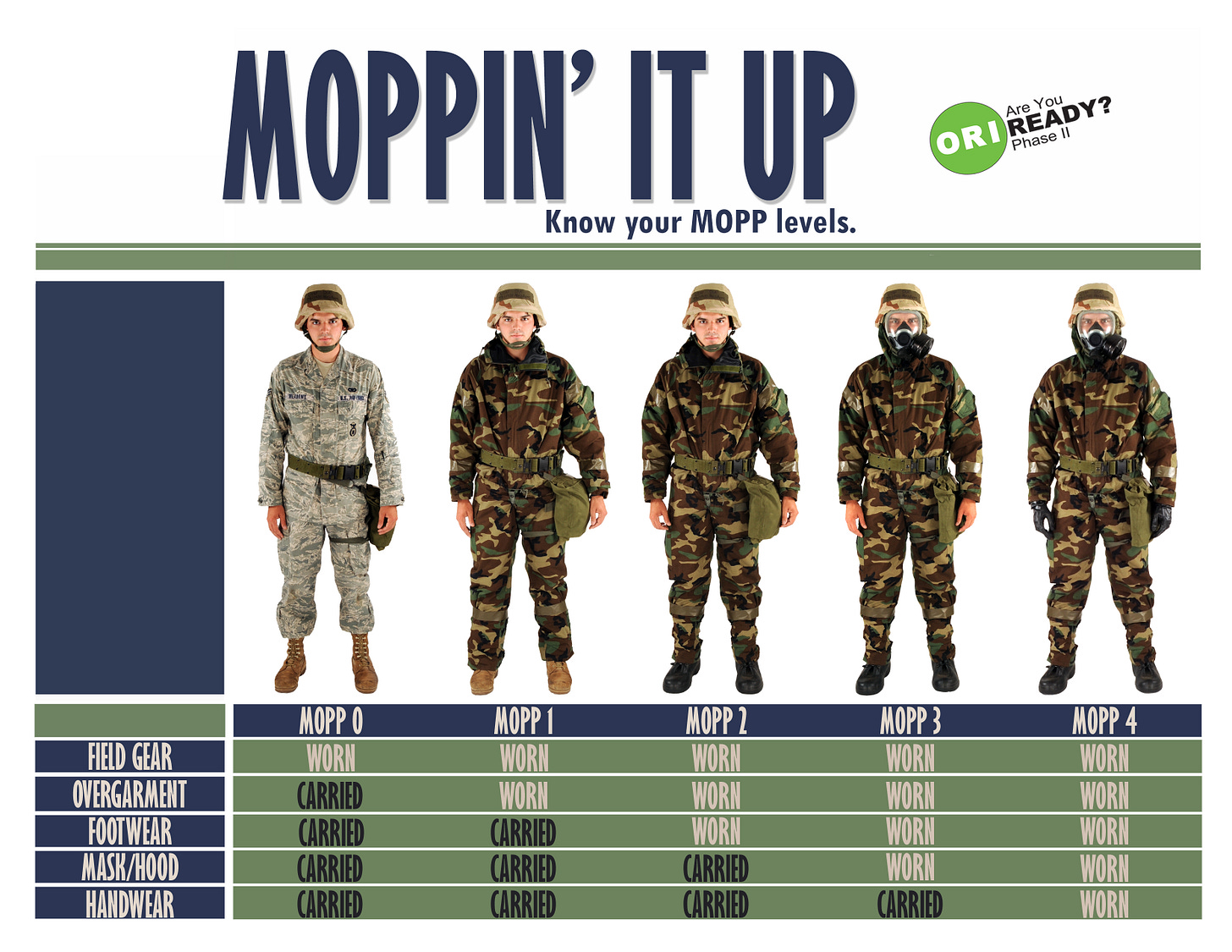

As a Field Radio Operator in an infantry battalion I had to carry everything the regular Marines did and then a 25 lbs. radio, a five pound piece of gear to encrypt and decrypt my radio transmissions and at least three extra batteries for each, which was another six pounds. So all together I carried 36 lbs. beyond what the regular grunts were carrying, which always somewhere around 60 or 70 lbs. When you have to carry that much weight you quickly learn what you really need and what you can leave behind. Since I never went anyplace really cold, I never packed my field jacket, sleeping bag, shelter half (half a tent so two Marines together could make one small tent.) or any extra layers of clothes, didn’t need them and didn’t want to carry them. The coldest place I ever went was Saudi Arabia and Kuwait during the Gulf War, it was raining and in the low 50’s but at that time I was wearing a MOPP (Mission Oriented Protective Posture) chemical weapons protective suit, so the temperature wasn’t too bad. Do you know what is really important to an infantry Marine? Their feet. When you spend as much time as we did walking around in the field, clean, dry socks are the most important thing a Marine infantryman (and their battery powered radio operator brothers) could have. Wet socks mean wet feet and wet feet lead to all kinds of issues including blisters and trench foot. Just as an example when a new Battalion Commander arrived at our unit he decided we would set the base record for 100km (62 mile) forced march. The record was 71 hours and his plan was for us to do it in 68 hours. Since this was a race and we were on our own base, we didn’t take much in the way of supplies. We had our shelter halves, poncho and poncho liners and the usual two gallons of water and whatever else we wanted to bring. Of course by then the vast majority of the 800 Marines in the battalion were Gulf War veterans and knew what was important. I took 14 pairs of sock at that was it. We were only going to be gone three days so extra clothes weren’t needed and no one in their right mind would have carried anything else. So at 8 am one day off we went walking at about three miles an hour for two hours and then a 15 minute break then rinse and repeat until we had gone 25 miles for the day. Then we made camp and slept until 6:30 am when we got up and started the whole process over again. every other break most of us would change our socks and at night we would rinse them out and dry them for the next day. The problem was were we using this newfangled gadget called GPS and the officers thought that we could navigate completely with GPS and not use maps. With the newness of that technology and their unfamiliarity with using it, we kept getting lost. In fact we got lost so often that we added an additional 35 miles to our march. Every time they noticed we were off course they would increase the pace until I almost had to jog to keep up. At the end we did the 97 miles in 75 hours setting a record no one will beat (because no one would want to). Another example of the infantryman’s preoccupation with socks would be my time during the Gulf War. During that conflict my unit, 3rd Battalion 7th Marine Regiment, was part of a thing called Task Force Grizzly which consisted of two infantry battalions 2/7 and 3/7 and an artillery battalion 3/11. The infantry battalions were “foot mobile” which means we walked everywhere we needed to go. The 100 miles from the Saudi Air Force base we landed, to the Kuwait border in four days and then another 30 miles once we crossed into Kuwait. The artillery of course had to have vehicles because of their guns but we walked everywhere. Because of that I changed my socks at least three times a day. I had packed seven pairs of underwear and fourteen pairs of socks and used what little extra water we had to rinse out those socks. Because of the situation, with the high possibility of Saddam Hussein using chemical weapons on us, we were in MOPP 2, the third highest level of readiness, the whole time I was there.

That meant we had had to wear to keep our chemical suits on at all times so all those underwear became redundant. There were a few times that chemical weapon detectors went off and we had to go to MOPP 4 but while it was concerning, we didn’t take any causalities from it and we were told they were all false alarms.

Those are a list of the most important things I learn in the Marines, not counting don’t get shot. If you wish to comment on my list, share this post, or subscribe to this stimulating publication, please click the buttons below.