In my last post, I covered the time between the end of the Six Day War and the build-up to the Yom Kippur War. Click below if you missed it.

Today I will look at the Yom Kippur War itself. This is another war that is not very well known outside of the region and it is important because it reset the balance of power in place after the Six Day War.

The main difference between the Yom Kippur and other Arab/Israeli wars was the existence of a very prominent border feature in the form of the Suez Canal. The Israelis thought they were safe behind the canal and the Egyptians needed to find a way to safely cross the canal in some kind of order if they were to have any hope of success.

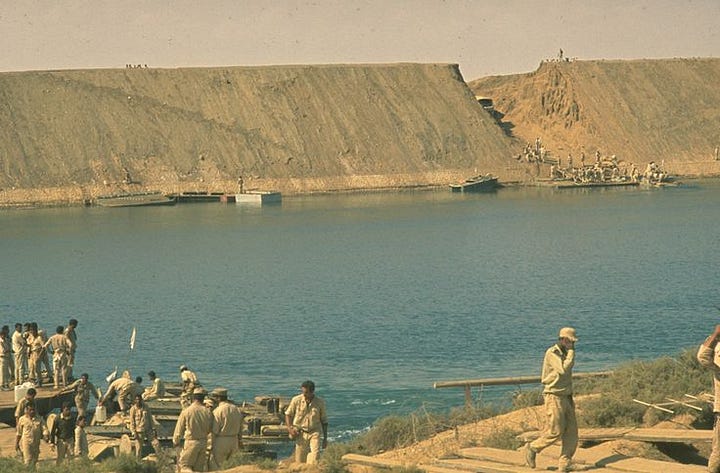

In the intervening time period between the end of the Six Day War and fall of 1973, the Israelis had constructed a large sand berm, along the edge of the Suez canal. Running the entire length of the canal, the berm was between 68 and 82 feet high and inclined at an angle of 45–65 degrees, preventing any armored or amphibious units from landing on the east bank of the Suez Canal without prior engineering preparations.

The Israelis estimated it would take at least 24 hours and probably a full 48 hours for the Egyptians to breach the sand wall and establish a bridge across the canal. In another defensive measure, and one to take advantage of the canal itself, the Israelis installed an underwater pipe system to pump crude oil into the Suez Canal, and when lit it would create a sheet of flame, that any attacking force would have to pass through.

Immediately behind this sand wall was the front line of Israeli fortifications, know as the Bar-Lev Line. Composed of 22 forts, with 35 strongpoints, each fort were designed to be manned by a platoon. The strongpoints, which were built several stories into the sand, were on average situated less than three miles from each other, but at likely crossing points they were less than 3,000 feet apart. The strongpoints incorporated trenches, minefields, barbed wire and sand embankments. Major strongpoints, near suspected crossing points had up to 26 bunkers with medium and heavy machine guns, 24 troop shelters, six mortar positions, four anti-aircraft bunkers and three firing positions for tanks. The strongpoints were surrounded by nearly fifteen circles of barbed wire and minefields to a depth of 220 yards. The bunkers and shelters provided protection against anything less than a 120 lb. bomb, and offered luxuries to the defenders such as air conditioning. Between 550–1100 yards behind the canal, there were prepared firing positions designed to be occupied by tanks assigned to the support of the strongpoints. In addition, there were eleven strongholds located 3–5 miles behind the canal, which were built along sandy hills. Each stronghold was designed to hold a company of troops.

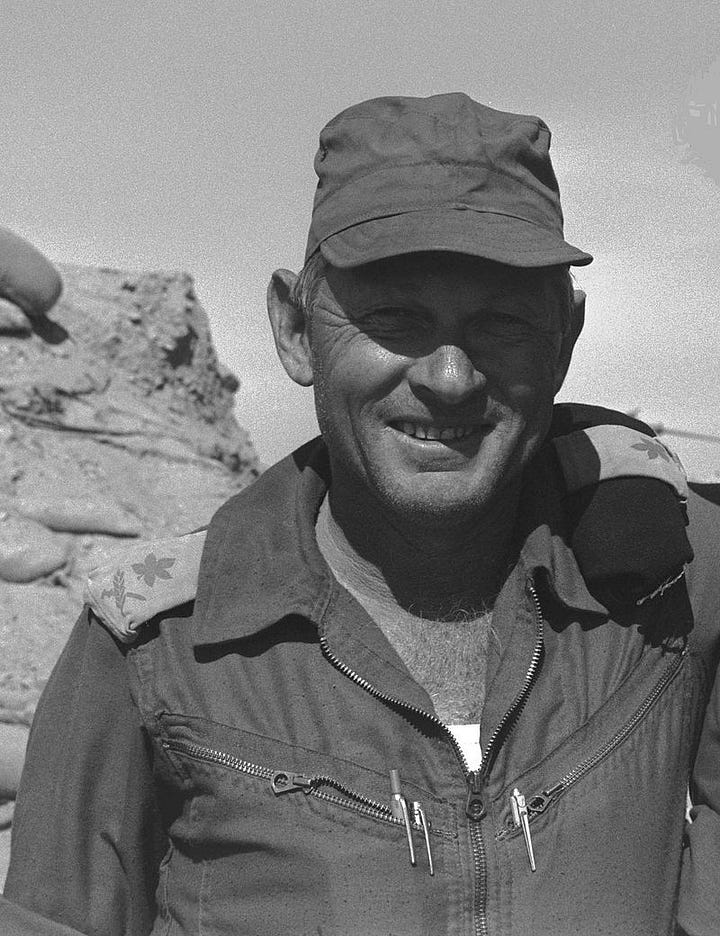

To support the Bar Lev Line, Israel built a well-planned and elaborate system of roads. Three main roads ran north–south, the first was Lexicon Road, running along the canal, allowing the Israelis to move between the fortifications and conduct patrols. The second was Artillery Road, around 6–7 miles from the canal. Its name came from the twenty artillery and air defense positions located along the road, linking armored concentration areas and logistical bases. The Lateral Road, 19 miles from the canal, was meant to allow the concentration of Israeli operational reserves which, in case of an Egyptian offensive, would counterattack the main Egyptian assault. A number of other roads running east to west, Quantara Road, Hemingway Road, and Jerusalem Road, were designed to facilitate the movement of Israeli troops towards the canal. However, not everyone in the IDF was thrilled by the Bar-Lev Line. Ariel Sharon, who had until a few months before been commander of the southern front, recognized the Bar-Lev Line as a death trap. He urged that it be abandoned and a new defense line established on high ground to the east so that the defenders could delay a head-on engagement with the Egyptians until reserve divisions had arrived. Un fortunately Chief of the General Staff Lieutenant General David Elazar decided to keep the defense line, as he saw it, the IDF's presence on the canal constituted a political card to be utilized in any future negotiations with Egypt, while also offering some tactical and intelligence advantage. Underlying this catastrophic decision, which tied Israeli strategy to the fate of the irrelevant forts, was the notion that the Egyptians were unlikely to dare a major canal crossing and that if they did they would be dealt with swiftly as they had been in 1967.

The defense of the Sinai depended upon two plans, Dovecote and Rock. In both plans, the Israeli General Staff expected the Bar-Lev Line to serve as a "stop line”, a defensive line that had to be held at all cost. Dovecote tasked an armored division to the defense of the Sinai. The division was supported by an additional tank battalion, twelve infantry companies and seventeen artillery batteries, with a total of 300 tanks, 70 artillery pieces and 18,000 troops. These forces were tasked with defeating an Egyptian crossing at or near the canal line. It called for around 800 soldiers to man the forward fortifications on the canal line. Meanwhile, along Artillery Road, a brigade of 110 tanks was stationed with the objective of advancing and occupying the firing positions and tanks ramparts along the canal in case of an Egyptian attack. There were two additional armored brigades, one to reinforce the forward brigade, and the other to launch a counterattack against the main Egyptian attack. Should the regular armored division prove incapable of repulsing an Egyptian attack, the Israeli army would activate Rock, mobilizing two reserve armored divisions with support elements; implementation of Rock signified a major war. Israeli planning was based on a 48-hour advance warning, given by intelligence services, of an impending Egyptian attack. During these 48 hours, the Israeli Air Force (IAF) would assault enemy air defense systems, while Israeli forces deployed as planned. The Israelis expected an Egyptian attack would be defeated by armored brigades supported by the superior IAF.

On the other side of the canal, Egyptian planers had to figure a way to surmount that barrier before any large-scale crossing could take place. Explosives were the obvious choice but it was quickly discovered that they would not be effective. It would take such a large amount of explosives that they could not be carried by a small force crossing the canal in rubber boats. Bulldozers and artillery were also considered and quickly deemed unrealistic for similar reasons. Of course the Israelis were not going to sit idly by and let a force of Egyptians cross the canal and place explosives or use bulldozers on the main barrier protecting their side of the canal. It was a young Egyptian officer, Baki Zaki Yousef, who suggested a small, light, gas powered pump shooting water drawn right from the canal, that would cause the berm to simply wash into the canal like a sand castle at the beach. The Egyptian military purchased 300 British-made pumps, each of which could blast 5900 square feet of sand per hour into the canal. They discovered that if three pumps were used together they could cut a hole in the berm in two hours.

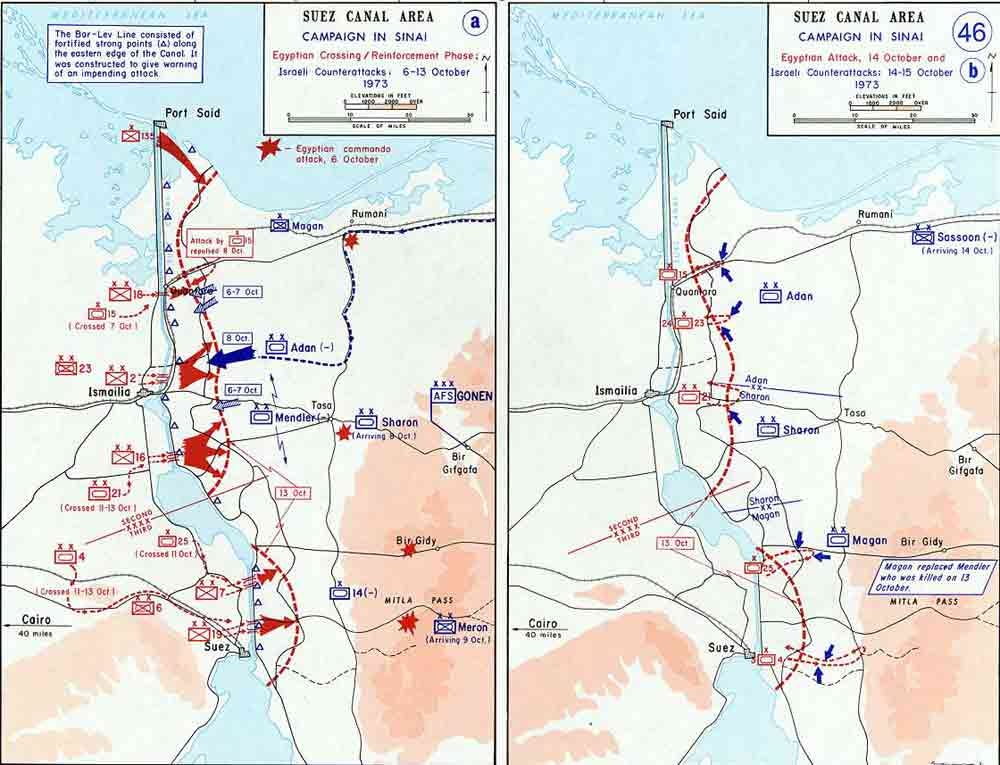

The Egyptians gathered five divisions totaling 100,000 soldiers, 1,350 tanks and 2,000 guns. Facing them, behind their 80 foot high berm, were 450 soldiers of the Jerusalem Brigade, spread out in 16 forts along the length of the canal. There were 290 Israeli tanks in all of Sinai, divided into three armored brigades, only one of which was deployed near the canal when hostilities commenced.

The Suez Campaign

During the night of October 5, Egyptian frogmen entering the water of the canal under the cover of darkness, swimming across the waterway, locating all the underwater crude oil pipes and disabled them, right under the noses of the IDF.

A few minutes before 2 p.m. on Yom Kippur, October 6, a swarm of low-flying Egyptian planes conducted simultaneous strikes against Hawk missile instillations, three command centers, three airbases, artillery positions, and several radar installation. The aerial assault was coupled with a barrage from more than 2,000 artillery pieces against the Bar Lev Line, rear area command posts and concentration areas. It was a barrage that made the desert floor shake. The crews of Colonel Amnon Reshef's 14th Armored Brigade, on alert in staging areas half an hour from the front, mounted their tanks and raced towards the canal as they had done in repeated exercises. The Egyptians, from high ramparts they had built on their side of the canal, had monitored those exercises closely. The Egyptian commandos who crossed the canal in rubber boats, under the cover of the bombardment, moved inland rapidly. As the leading tanks arrived, they were met by swarms of Egyptians rising out of shallow foxholes with rocket propelled grenades (RPGs). The tanks which escaped the initial barrage, pulled back a few hundred meters out of RPG range, it was not far enough, however. Red lights seen wafting lazily towards them proved to be wire-guided AT-3 Sagger missiles, the operators aligning the bright light on the missile with their targets. The missiles had roughly the range of the tank’s guns, 3,000 meters, and were as lethal. At those ranges the Sagger operators lying in the sand could not be seen.

The IDF tankers had not been told of the missile's existence and did not know what was hitting them. Intelligence had learned months before of the Sagger's arrival in the Arab arsenal, but the Armored Corps, not overly concerned, had not yet passed the warning on to field units, let alone proposals how to cope with it. Left to their own devices, the young tankers in Reshef's brigade came up with an answer to the Sagger, that first day, at least one that was partially effective. Taking note of the missile's slow flight - the slowness necessary to enable the Sagger operator to guide it onto target - they tailored a new tactic. As soon as any tank commander spotted a red light, he would shout "missile" into the radio. Every tank in the area would begin moving to throw up a cloud of dust, obscuring the sight of the missileer, with the added benefit of no longer being a stationary target. They would also begin shooting in the general direction from which the missile was coming, in the hope that it would throw the Sagger operator off his aim even if it was unlikely that they would hit him.

Simultaneously, fourteen Egyptian Tupolev Tu-16 Badger bombers attacked Israeli targets in the Sinai with Kelt missiles, while two more Badgers fired missiles at a radar station in central Israel. The attack was a warning to Israel that Egypt could strike targets in Israel, if Israel bombed targets in Egypt.

Under cover of the artillery barrage, the initial wave of 4,000 assault troops began crossing the canal in 2,500 dinghies and wooden boats, using smoke canisters at the crossing points to provide cover. The first wave was lightly equipped, armed with RPG-7s, Strela-2 AA missiles and rope ladders to deploy on the sand wall.

Among the first wave were combat engineers and several units of Sa'iqa (commando forces), who were tasked with setting up ambushes on the Israeli reinforcement routes. The Sa'iqa attacked command posts and artillery batteries as well, in order to deny the Israelis control over their forces, while the engineers breached the minefields and barbed wire surrounding Israeli defenses. Immediately following them, more engineers transported the water pumps to the base of the berm on the opposite bank and began setting them up. Twelve waves followed at five separate crossing points. The pumps did their job creating huge gaps in the berm at all five crossing points.

This allowed Egyptian engineers to begin laying bridges across the canal, that, once in place, allowed additional infantry with the remaining portable anti-tank weapons, as well as vehicles including tanks to start crossing the bridges, which they did starting at 8:30 pm. The Israeli Air Force tried air raids to prevent the bridges from being erected, but took losses from Egyptian SAM batteries. Even when the Israeli planes were able to drop their loads, the attacks were ineffective, because the sectional design of the bridges enabled quick repairs when hit.

On this first day of the war, Reshef's brigade, and a sister battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Yom Tov Tamir, at the northern end of the canal, without air support and virtually no artillery, found themselves confronting an attack by four Egyptian divisions displaying new weaponry and a determination that came as a total surprise. The Egyptian's artillery and airstrikes prevented Israeli forces from reinforcing the Bar Lev Line and the assault forces proceeded to attack the Israeli fortifications. Despite fierce resistance, the troops manning the Bar-Lev forts were overwhelmed, although the northernmost fortification of the Bar Lev Line, Fort Budapest, withstood repeated assaults and remained in Israeli hands throughout the war.

The Egyptians also attempted to land several heliborne commando units in various areas in the Sinai to hamper the arrival of Israeli reserves. This attempt met with disaster as the Israelis shot down 20 helicopters, inflicting heavy casualties. Despite their heavy losses, the Egyptian commandos would play an important role in preventing reinforcements from reaching the fighting. One battalion captured the Ras Sidr Pass south of Port Tawfiq. The battalion held its position for the remainder of the war under extremely difficult conditions, preventing Israeli reserves from using the pass to reach the front. Another two companies blocked the pass between Tasa and Gifgafa managing to block Israeli reserves for eight hours before being completely destroyed. In northern Sinai, a company established itself along the coastal road between Romani and Baluza. The following day, it ambushed Colonel Natke Nir's 217th Reserve Armored Brigade, destroying 18 tanks and other vehicles and blocking the coastal road for six hours.

On October 7, the Egyptians consolidated their initial positions, enlarging the bridgeheads an additional three miles. In the north, the Egyptian 18th Division under the command of Brigadier General Fuad 'Aziz Ghali attacked the town of El-Qantarah, engaging Israeli forces in and around the town. The fighting there was conducted at close quarters, and was sometimes hand-to-hand. The Egyptians were forced to clear the town building by building, but by evening, most of the town was in Egyptian hands and by the next day it was completely clear.

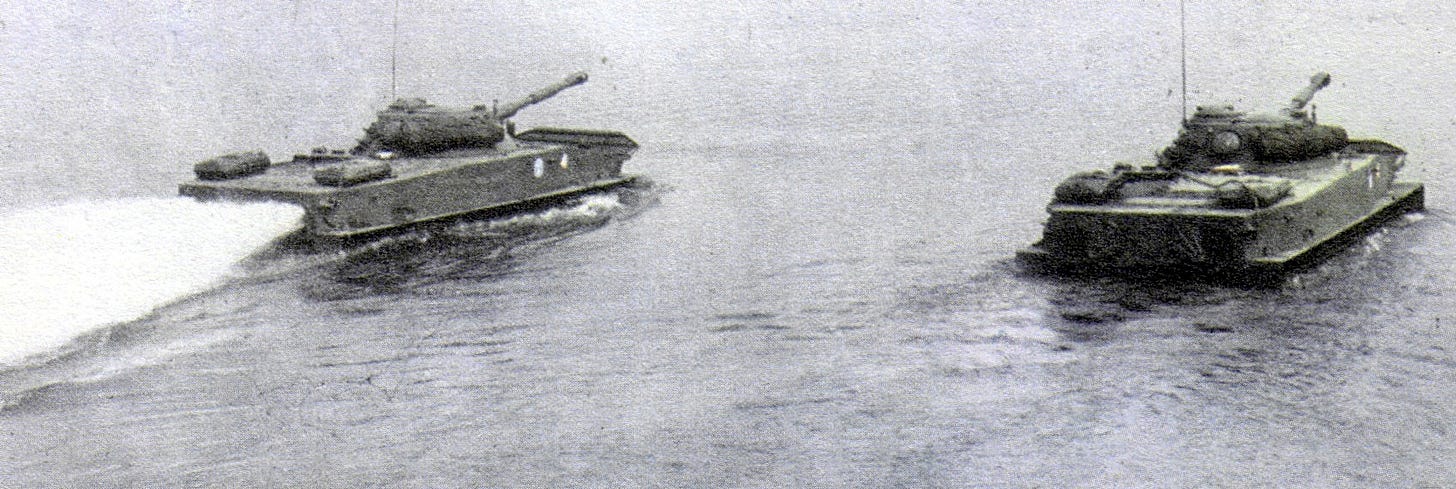

At the Great Bitter Lake, (2/3 of the way down the canal towards the Red Sea), the Egyptian 130th Amphibious Brigade, commanded by Colonel Mahmoud Shu'aib, performed its own crossing. The brigade, composed of the 602nd and 603rd Mechanized Infantry Battalions with 1,000 men, including a Sagger anti-tank battalion, an anti-air battalion, 20 PT-76 tanks and 100 BTR-50 armored personnel carriers, was tasked with finding and destroying enemy installations at the entrances of the Gedy and Mitla Passes.

The sand rampart that lined the entire Suez Canal did not exist in the Bitter Lakes, and the brigade reached the opposite bank without any losses, clearing a minefield on the eastern side that was blocking their advance. After regrouping outside the minefield, the 603rd was attacked by a company of tanks from Fort Putzer, a fortification located near the Bitter Lake. The 603rd had been reinforced with a tank hunting detachment from the 7th Division, and managed to destroy two tanks and three armored vehicles before the Israelis withdrew. Afterwards, its original assignment was canceled and it was ordered to capture Fort Putzer. After being forced to retreat to the fort, the Israeli force abandoned the position. On October 9 the 603rd occupied Fort Putzer and despite being cut off and coming under numerous attacks, held it, for the remainder of the war. The 602nd began to move eastwards after dusk, and stumbled upon an Israeli battalion of 35 tanks along Artillery Road, nine miles from Bitter Lake. The battalion's ten PT-76s were outnumbered and outgunned by the heavier Israeli M-48 Pattons and their 105 mm guns. The manually guided Saggers were difficult to operate at night, and Israeli tanks were employing blinding xenon floodlights, making it even more difficult for the gunners to score hits on the Pattons. Caught in the open desert, the 602nd lost many of its tanks and armored vehicles, suffering significant casualties.

Meanwhile, Israeli Southern Command attempted to pinpoint the main Egyptian effort in order to launch a counterattack with the 401st Armored Brigade under the command of Colonel Dan Shomron. Unfortunately, there was no main axis of attack, it was a general offensive along the entire canal. As a result, Southern Command wasted several critical hours. More errors occurred when Colonel Amnon Reshef moved his tank brigade forward, without conducting the appropriate reconnaissance beforehand, causing his unit to fall into Egyptian ambushes. By then Israeli armored losses had reached 100 tanks. The magnitude of Israeli losses stemmed from their repeated attempts to reach their comrades in the Bar Lev Line, where they ran into aggressive ambushes by Egyptian soldiers.

In the afternoon of October 7, the twelfth and final wave of troops crossed the canal, bringing the total of Egyptian troops on the eastern shore to 32,000 men. Meanwhile, Egyptian General Headquarters worked on organizing its forces on the east bank. Egyptian troops had crossed the canal with one day of supplies. By Sunday it became necessary to resupply these forces, but administrative and supply units were in disarray, and still on the western shore of the canal. October 7, offered a relative lull in the fighting, allowing the Egyptians to organize battlefield administration. For example, at the 19th Division's bridgehead to the south, the Egyptian engineers were having difficulties in laying the bridges because of the terrain on the east bank. All three bridges there were abandoned and instead, supplies and reinforcement destined for the 19th Division were transferred over the 7th Division's bridges to the north, where engineers had not had any issues with their bridges. While there was a lull in the fighting, it did not cease entirely. For the rest of the day most of the fighting was centered around the besieged Israeli defenses and strong points that still resisted.

On October 8 the five bridgeheads were consolidated into two larger bridgeheads, the Second Army and its three divisions occupied El-Qantarah in the north to Deversoir in the south, while the Third Army with two divisions occupied the southern end of the Bitter Lakes to a point southeast of Port Tawfiq (at the far end of the canal). These two bridgeheads incorporated a total of 90,000 men and 980 tanks. Each division occupied defensive positions with two infantry brigades in forward positions, one mechanized infantry brigade in a support position and one armored brigade in reserve. The Egyptians had established robust anti-tank defenses along their lines employing Sagger ATGMs and RPG-7, along with B-10 and B-11 anti tank recoilless rifles.

Shortly after midnight on October 8, optimistic field reports expecting an imminent Egyptian collapse caused Southern Command leader Major General Shmuel Gonen to alter plans for an upcoming attack. Avraham “Bren” Adan and his 162nd Armored Division would now attack in the direction of the strong points at Firdan and Ismailia. The change was not formulated on precise tactical intelligence, and would come to cause some confusion among Israeli commanders for the rest of the day.

Gonen wanted Adan to reach the Hizayon strongpoint, and that morning contacted Chief of Staff Major General David Elazar in Tel Aviv to request a crossing of the canal. Gonen either downplayed or ignored negative reports and only told Elazar of positive developments. Elazar, who was at a meeting, communicated with Gonen through his assistant and approved of a crossing. The order was also given for Ariel Sharon's 143rd Reserve Armored Division to move south. At 10:40, Gonen ordered Adan to cross to the west bank and Sharon to move towards Suez City. Short of forces, Adan requested that Sharon send a battalion to protect his southern flank. Gonen consented, but Sharon would not comply, and consequently several critical positions would be lost to the Egyptians later on. Just before the assault commenced, one battalion of Gabi Amir’s 460th Brigade, disengaged to restock on ammunition and fuel. The other battalion proceeded with the assault at 11:00, 25 tanks carried out an assault planned to be performed by 120 tanks. The Israelis broke through the initial line of Egyptian troops and advanced to within 2,600 feet of the canal. At this point, the Israelis came under heavy fire from anti-tank weaponry, artillery and tanks. The battalion lost 18 tanks within minutes, and most of its commanders were either killed or wounded. By now Nir had disengaged at El-Qantarah, leaving a battalion behind, and arrived opposite the Firdan bridge, near Ismailia at 12:30 with two tank battalions. While Amir and Nir discussed plans for an attack, Colonel Keren arrived with his 500th Armored Brigade, and Adan ordered him to support Nir and Amir by attacking towards Purkan. Meanwhile, Sharon left Tasa and headed for Suez City, leaving a single reconnaissance company to hold vital ridges. Instead, Keren's brigade gained responsibility for these areas, but Sharon's action further endangered Adan's position. Amir's brigade was now down to one battalion, which was to attack with Nir's brigade of 50 tanks. To Amir's surprise, a reserve armored battalion of 25 tanks commanded by Colonel Eliashiv Shemshi arrived in the area, en route to Keren's brigade. Short of forces, Amir, with Adan's approval, commandeered Shemshi's battalion, and ordered him to provide covering fire for Nir's assault on the Firdan bridge.

Brigadier General Hassan Abu Sa'ada the 2nd Division commander, had the 24th Armored Brigade as the divisional reserve, but was under strict orders to commit it only in the case of an Israeli penetration. At around 1:00 pm, a recon group from 2nd Division discovered 75 tanks concentrating north east of the bridgehead. Ten minutes later the Egyptians intercepted a radio signal in Hebrew, Nir was informing his command that he was ready to attack within twenty minutes. With little time left, General Sa'ada decided on a risky move. Estimating, (correctly as it turned out), that the attack would be directed at the point where his two forward brigades met, the weakest portion of his lines, he planned to draw Israeli forces to within 1.5 miles of the canal before engaging them from all sides and committing all his anti-tank reserves. At 1:30 pm, Amir and Nir’s brigades began the attack. A lack of coordination and communication difficulties between the brigades hampered the attack. Nir's two battalions attacked at the same time in two echelons. The Egyptians allowed the Israelis to advance, then encircled them. When the attackers entered the prepared killing zone, Egyptian armor of the 24th Brigade opened fire on the advancing tanks, complemented by infantry anti-tank weapons on either flank of the Israeli forces, while tank hunting detachments attacked from the rear. Within just 13 minutes, most of the Israeli force, 50 tanks, were destroyed. By the end of the attack Nir had just four operational tanks remaining, including his own. Gabi Amir's battalion, attacking to Nir's right, was forced to halt their advance after encountering stiff resistance. Amir requested air support several times, but did not receive any.

During the afternoon of the 8th, Egyptian artillery barrages and air strikes took place along the entire front. The Israelis, who believed they were on the counter-offensive, were surprised at the sight of advancing Egyptian troops. While not all advancing Egyptian units managed to reach the 7.5 mile mark necessary to control Artillery Road, each division held positions more than 5.6 miles deep. In Second Army's sector, the 16th Infantry Division was the most successful by occupying the strategic positions of Mashchir, Televiza, Missouri and Hamutal. Hamutal was 9.3 miles from the canal and overlooked the junction of Ismailia and Artillery Roads. The deepest penetration was in Third Army's sector, where they penetrated to a depth of 11 miles. The Egyptians also captured several additional Bar Lev forts.

The Israelis now made an attempt to regain the lost ground. Keren's brigade organized for an assault on Hamutal Hill. One battalion provided covering fire, while two battalions attacked with 27 tanks. Nearly 3,300 feet from the Egyptian positions, one of the battalion commanders was killed when his tank took a direct hit, disrupting his battalion's attack. The other battalion continued fighting until dusk and lost seven tanks. Gonen, who was starting to realize the gravity of Adan's position, ordered Sharon to pull back and return to his initial position. The 421st Armored Brigade under Haim Erez arrived to offer assistance to Keren, but poor coordination between the commanders led to the failure of further attempts to capture Hamutal Hill. By the end of the day Adan's division alone had lost around 100 tanks.

By October 9 the front lines had stabilized. The Egyptians were unable to advance further, and Egyptian armored attacks on October 9 and 10 were repulsed with heavy losses. The Egyptian 1st Mechanized Brigade launched a failed attack southward along the Gulf of Suez in the direction of Ras Sudar, leaving the safety of their SAM umbrella, the force was attacked by Israeli aircraft and suffered heavy losses.

Between October 10 and 13, both sides refrained from any large-scale actions, and the situation was relatively stable. Both sides launched small-scale attacks. The Egyptians used helicopters to land commandos behind Israeli lines. Some Egyptian helicopters were shot down, and those commando forces that managed to land, were quickly destroyed by Israeli troops. In one key engagement on October 13, a particularly large Egyptian incursion was stopped and close to a hundred Egyptian commandos were killed. However the Israelis launched a commando raid of their own, against an Egyptian signals-intercept site at Jebel Ataqah. This raid seriously disrupted Egyptian command and control and contributed to its breakdown during the engagement.

On October 12, Israeli intelligence detected signs that the Egyptians were gearing up for a major armored thrust set to kick off on October 14. At dawn, an engagement now known as the Battle of the Sinai began. In preparation for the attack, Egyptian helicopters set down 100 commandos near the Lateral Road to disrupt the Israeli rear. An Israeli reconnaissance unit quickly subdued them, killing 60 and taking numerous prisoners. Still bruised by the extensive losses their commandos had suffered on the opening day of the war, the Egyptians were unable or unwilling to implement further commando operations that had been planned in conjunction with the armored attack. Egyptian Chief of Staff General Saad el-Shazly strongly opposed any eastward advance that would leave his armor without adequate air cover. He was overruled by General Ismail and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, whose aims were to seize the strategic Mitla and Gidi Passes and the Israeli nerve center at Refidim, which they hoped would relieve pressure on the Syrians, (who were by now on the defensive, see Part XV), by forcing Israel to shift divisions from the Golan to the Sinai.

The 2nd and 3rd Armies were ordered to attack eastward in six simultaneous thrusts over a broad front, leaving behind five infantry divisions to hold the bridgehead. The attacking forces, consisting of 1,000 tanks would not have SAM cover, so the Egyptian Air Force (EAF) was tasked with their defense against Israeli aerial attacks. Armored and mechanized units initiated the attack on October 14 with artillery support. They were up against 750 Israeli tanks. The Egyptian units launched head-on-attacks against the waiting Israeli defenses. At least 250 Egyptian tanks and some 200 armored vehicles were destroyed and Egyptian casualties exceeded 1,000. Fewer than 40 Israeli tanks were hit, and all but six of them were repaired by maintenance crews and returned to service. Israeli casualties numbered 665.

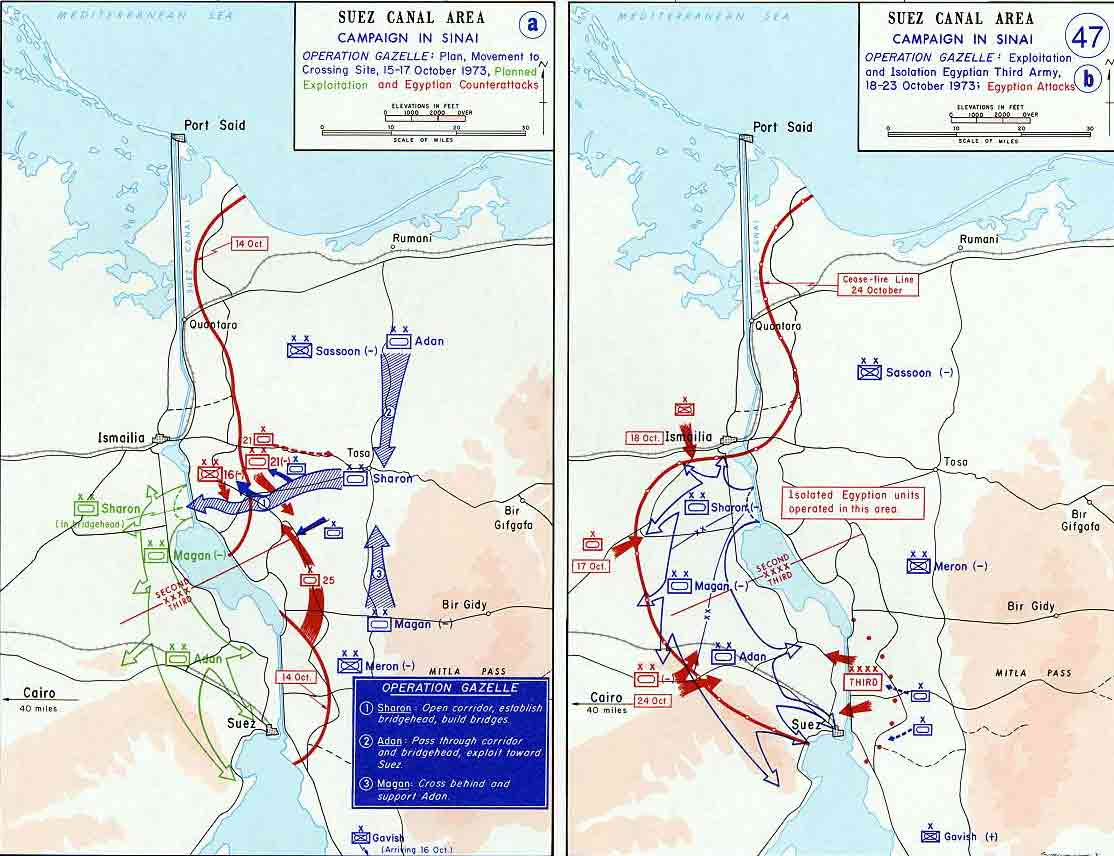

At this point, General Sharon advocated an immediate crossing at Deversoir at the northern edge of Great Bitter Lake. Earlier, on October 9, a reconnaissance force attached to Colonel Amnon Reshef’s brigade had detected a gap between the Egyptian Second and Third Armies in this sector. The existence of the gap was confirmed by a US message after it was spotted by a SR-71 spy plane.

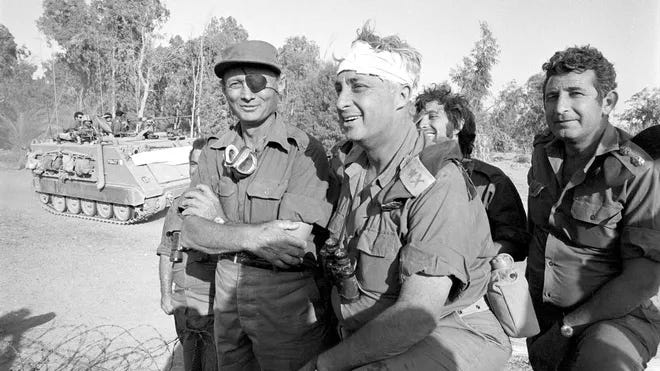

The Israelis followed the Egyptian failed attack of October 14 with a multidivisional counterattack through the gap between the Egyptian Second and Third Armies. Sharon's 143rd Division, now reinforced with a paratroop brigade commanded by Colonel Danny Matt, was tasked with establishing bridgeheads on both the east and west banks of the canal. The 162nd and 252nd Armored Divisions, commanded by Generals Avraham Adan and Kalman Magen, respectively, would then cross through the breach to the west bank of the canal and swing southward, encircling the 3rd Army. The offensive was code-named Operation Gazelle or alternatively, Operation Valiant.

Despite the success the Israelis were having on the west bank, Generals Bar-Lev and Elazar ordered Sharon to concentrate on securing the bridgehead on the east bank.

He was ordered to clear the roads leading to the canal as well as a position known as the Chinese Farm (an Egyptian agriculture research facility that used Japanese equipment that Israeli observers thought were Chinese), just north of Deversoir, the Israeli crossing point. Sharon objected and requested permission to break out of, and expand the bridgehead on the west bank, arguing that such a maneuver would cause the collapse of Egyptian forces on the east bank. But the Israeli high command was insistent, believing that until the east bank was secure, forces on the west bank could be cut off.

On the night of October 15, under a full moon, Lieutenant Colonel Yoav Brom led his battalion across the dunes. As it neared the canal, he peeled off to secure a stretch along the waterway from which Matt's paratroopers would attempt to cross. Lieutenant Colonel Amram Mitzna now led the column, with Reshef just behind him, followed by two other battalions. The entry point into the Egyptian lines was the intersection of two roads - Lexicon, which paralleled the canal, and Tirtur, an east-west road which marked the southern perimeter of the Third Army. The Egyptians positioned around the intersection initially took the tanks coming out of the darkness to be friendly. Half of Mitzna's battalion had crossed the intersection before the Egyptians opened fire. Several tanks were set aflame, blocking the road. The tanks which had already entered the Egyptian lines pushed into the heart of the defenses, firing in every direction. Egyptian soldiers covered with blankets against the desert cold could be seen emerging from foxholes in the reddish light of burning vehicles and the flaring of exploding ammunition dumps. A large anti-aircraft missile, hit by shellfire, took off in wild gyrations. As the tank gunners hit vehicles, artillery pieces and fuel tankers, the commanders in open turrets hurled grenades at infantrymen and fired Uzis, the tanks' machine guns joining in. Tank commanders took to crushing ammunition crates under their treads instead of shooting at them, in order to avoid the glare of explosions that would expose the tanks to RPG teams. The Egyptians quickly recovered from the surprise and began fighting back. The two sides were soon thoroughly intermingled. Battalion commander Avraham Almog, who had turned eastward into the heart of the Chinese Farm with 10 tanks, halted to form a stationary battle line. The tanks destroyed ammunition dumps, cut down infantrymen and engaged enemy armor. At one point, an Egyptian tank approaching from the rear mistakenly joined the Israeli line. The startled commander of the neighboring Israeli tank turned his gun on him. The gunner squeezed the trigger but nothing happened, it was a misfire. The Egyptian tank commander glanced over, and found himself looking down the barrel of a tank cannon. Realizing his error, he began swiveling his own gun toward the Israeli tank. By this time, however, the commander of the tank on the other side of the Egyptian had backed off to gain sufficient room to fire and destroyed the intruder.

Reshef had positioned himself in the middle of the chaotic battlefield, coordinating his far-flung forces by radio. At the same time he was firing his machine gun so relentlessly at targets all about him that his hands were cut from cocking the weapon. At one point, five Egyptian tanks lumbered out of the darkness, oblivious to the single stationary tank which they may have presumed to be part of the battlefield debris. Reshef ordered his gunner to prepare for rapid fire by assembling shells. At Reshef's command, the gunner hit four of the tanks, the fifth escaping. The brigade commander informed Sharon on the radio that he had just destroyed four tanks. It was not customary to report tank kills on the radio, but his men would be listening and Reshef wanted them to know that their commander was fighting alongside them. Hundreds of gutted vehicles, from jeeps to tanks, were strewn over the desert floor by now, along with the bodies of Egyptian and Israeli soldiers. Charred Israeli and Egyptian tanks lay alongside each other, some with their turrets blown off, some upended. Despite repeated attempts to subdue the Egyptian forces blocking the Tirtur-Lexicon intersection, it remained closed, surrounded by an ever expanding semicircle of destroyed Israeli tanks. Colonel Brom was killed in one of the attacks. At dawn, another attack, in company strength, was launched. In the early light, the Israelis could make out the formidable Egyptian disposition for the first time. Eight Egyptian tanks sheltering behind earthen mounds 550 yards away were hit, as were infantrymen firing from the lips of deep irrigation trenches where they had found ready cover. The Israeli tanks, firing from behind the destroyed tanks littering the intersection, were unscathed, but the attack force was almost out of ammunition and withdrew. Reshef himself now gathered remnants of the reconnaissance battalion and led a final attack on the intersection. This time, the defenders who had stood all night against repeated attacks raised the white flag. More than a third of the tank crewmen and paratroopers Reshef had taken into the Chinese Farm were casualties - 128 dead and 62 wounded. Of his 97 tanks, 56 were lost.

The Egyptians, although suffering far heavier losses, had not panicked and continued to block the rest of Tirtur and to keep the Akavish Road under a harassing fire from a distance. The bridges could not get through to the canal until both roads were safe from enemy fire. The following night a paratroop battalion under Yitzhak Mordechai was ordered to clear Tirtur Road from its eastern end, several kilometers from its junction with Lexicon. With no time for reconnaissance, the battalion walked into an ambush and was severely mauled - 41 dead and more than 100 wounded, but the battle drew the Egyptians away from positions dominating Akavish Road, and pontoons were pushed through to the canal. Incremental pressure finally drove the last of the Egyptian defenders from the Chinese Farm. This enabled the creation of a corridor down which Major General Avraham Adan's division could cross the canal. The Battle of Chinese Farm was the biggest tank battle since the Battle of Kursk in World War II and cost both sides over 100 tanks. Minister of Defense, Moshe Dayan said:

"I am no novice at war or battle scenes, but I have never seen such a sight, not in reality, or in paintings, or in the worst war movies. Here was a vast field of slaughter stretching as far as the eye could see”.

Ariel Sharon had his own poignant account of the battle:

"It was as if a hand-to-hand battle of armor had taken place. Coming close, you could see the Egyptian and Jewish dead lying side-by-side, soldiers who had jumped from their burning tanks and died together. No picture could capture the horror of the scene, none could encompass what had happened there."

After the corridor was finally forced open, 750 of Colonel Matt's paratroopers crossed the canal in rubber dinghies. They were soon joined by infantry and tanks ferried on motorized rafts. The force encountered no resistance initially and fanned out into raiding parties, attacking supply convoys, logistic centers and anything else of military value, priority was given to any SAM sites found. Every SAM site that was destroyed, punched a bigger hole in the Egyptian anti-aircraft screen and enabled the IAF to strike Egyptian ground targets more aggressively.

20 Israeli tanks and seven M-113 APCs under the command of Colonel Haim Erez crossed the canal and penetrated 7.5 miles into Egypt, taking the Egyptians by surprise. For the first 24 hours, Erez's force attacked SAM sites and military columns with impunity, including a October 16, raid on Egyptian antiaircraft missile bases, in which three were destroyed. On the morning of October 17, the force was attacked by the 23rd Egyptian Armored Brigade, but managed to repulse the attack. Other IDF forces attacked entrenched Egyptian forces overlooking the roads to the canal. After three days of bitter and close-quarters fighting, the Israelis succeeded in dislodging the numerically superior Egyptian forces. The Israelis lost 56 tanks but the Egyptians suffered heavier casualties, including 118 tanks destroyed and 15 captured.

By this time, the Syrians no longer posed a threat and the IAF were able to shift more air forces to the Sinai. The combination of a weakened Egyptian SAM umbrella and a greater concentration of Israeli aircraft meant that the IAF was now capable of greatly increasing sorties against Egyptian military targets.

When Israeli jets began attacking Egyptian SAM sites and radars, General Ismail withdrew much of the air defense equipment. This in turn gave the IAF still greater freedom to operate in Egyptian airspace. Israeli jets also attacked and destroyed underground communication cables at Banha in the Nile Delta, forcing the Egyptians to transmit selective messages by radio, which could, of course, be intercepted. However, Israel refrained from attacking economic and strategic infrastructure following an Egyptian threat to retaliate against Israeli cities with Scud missiles. The Egyptian Air Force attempted to interdict IAF sorties and attack Israeli ground forces, but suffered heavy losses in dogfights and in a turnabout, from Israeli SAMs.

The Egyptians, meanwhile, failed to grasp the extent and magnitude of the Israeli crossing, nor did they appreciate its intent and purpose. This was partly due to attempts by Egyptian field commanders to obfuscate reports concerning the Israeli crossing and partly due to a false assumption that the canal crossing was merely a diversion for a major IDF offensive targeting the right flank of the Second Army. Consequently, on October 16 General Shazly ordered the 21st Armored Division to attack southward and the 25th Independent Armored Brigade (with their newer T-62 tanks) to attack northward in a pincer action to eliminate the perceived threat to the Second Army. The Egyptians failed to scout the area and were unaware that by now, Adan's 162nd Armored Division was in the vicinity. Moreover, the 21st and 25th failed to coordinate their attacks, allowing General Adan's Division to meet each force separately. General Adan first concentrated his attack on the 21st Armored Division, destroying 50–60 Egyptian tanks and forcing the remainder to retreat. He then turned southward and ambushed the 25th Independent Armored Brigade, destroying 86 of its 96 tanks and all of its APCs, while only losing three tanks.

Egyptian artillery shelled the Israeli bridge over the canal on the morning of October 17, and the Egyptian Air Force launched repeated raids, some with up to 20 aircraft, to take out the bridge and rafts. During these raids the Egyptians had to shut down their SAM sites to prevent friendly fire incidents, allowing Israeli fighters to intercept the Egyptians. The Egyptians lost 16 planes and seven helicopters, while the Israelis lost six planes. The Israeli bridge was damaged several times and the headquarters of the 243rd Paratroop Brigade, which was near the bridge, was also hit, and Danny Matt as well as his deputy were wounded. During the night, the bridge was repaired, but only a trickle of Israeli forces were able to cross. The Egyptians would continue to attack the bridgehead until the ceasefire, firing tens of thousands of shells into the area of the crossing. Egyptian aircraft attempted to bomb the bridge every day, and helicopters launched suicide missions, making attempts to drop barrels of napalm on the bridge and bridgehead. The bridges were damaged multiple times, and had to be repaired at night. The attacks caused heavy casualties, and many tanks were sunk when their rafts were hit. Egyptian commandos and frogmen with armored support launched a ground attack against the bridgehead, which was repulsed with the loss of 10 tanks. Two subsequent Egyptian counterattacks were also beaten back.

After the failure of the October 17 counterattacks, the Egyptian General Staff slowly began to realize the magnitude of the Israeli offensive. Early on October 18, the Soviets showed Sadat satellite imagery of Israeli forces operating on the west bank. Alarmed, Sadat dispatched Shazly to the front to assess the situation first-hand. He no longer trusted his field commanders to provide accurate reports. Shazly confirmed that the Israelis had at least one division on the west bank and were widening their bridgehead. He advocated withdrawing most of Egypt's armor from the east bank to confront the growing Israeli threat on the west, but Sadat rejected this recommendation outright and even threatened Shazly with a court martial. Egyptian Commander in Chief Colonel General (yes, Colonel General) Ahmad Ismail Ali recommended that Sadat push for a ceasefire to prevent the Israelis from exploiting their successes.

Israeli forces were by now pouring across the canal on two bridges, and motorized rafts. Israeli engineers under Brigadier General Dan Even had worked under heavy Egyptian fire to set up the bridges, and over 100 were killed with hundreds more wounded. The crossing was difficult because of Egyptian artillery fire, though by 4:00 am, two of Adan's brigades were on the west bank of the canal.

On the morning of October 18, Sharon's forces on the west bank launched an offensive toward Ismailia, slowly pushing back an Egyptian paratroop brigade to enlarge the bridgehead. The 14th Armored Brigade continued to push the Egyptian paratroopers north towards Ismailia until the Israelis were within 5 or 6 miles of the city. Sharon hoped to seize the city and thereby sever the logistical and supply lines for most of the Egyptian Second Army. As the Israelis pushed towards Ismailia, the Egyptians fought a delaying battle, retreating into defensive positions further north as they came under increasing pressure from the Israeli ground offensive and airstrikes. On October 21, the 14th Brigade was occupying the city's outskirts, but facing fierce resistance from Egyptian paratroopers and commandos. The 243rd Paratroop Brigade pushed the Egyptians back far enough for the Israeli bridges to be out of sight of Egyptian artillery observers, though the Egyptians continued shelling the area. On October 22, Ismailia's Egyptian defenders were holed up in their last line of defense. At around 10:00 am, the Israelis renewed the attack, moving toward Jebel Mariam, Abu 'Atwa and Nefisha. The paratroopers were engaged in intense fighting but, held the high ground and were able to repel the attack. Meanwhile, the Israelis concentrated artillery and mortar fire against the commando positions at Abu 'Atwa and Nefisha but were unable to dislodge them. The Israeli advance towards Ismailia was halted 6 miles from the city. IDF forces failed to completely encircle Ismailia or cut the supply lines for the Egyptian Second Army.

The same day, Sharon's last remaining unit on the east bank, the 421st Brigade, moved north to take Orcha, an Egyptian logistics base defended by a commando battalion. Israeli infantrymen cleared the trenches and bunkers, supported by tanks. The position was secured before nightfall. The fall of Orcha caused the collapse of the Egyptian defensive line, allowing more Israeli troops into the area, where they were able to support troops facing Missouri Ridge, an Egyptian-occupied position on the Bar-Lev Line that could pose a threat to the Israeli crossing. One Israeli battalion attacked from the south, destroying 20 tanks and overrunning infantry positions before being halted by a minefield and a wave of Sagger missiles. Another battalion attacked from the southwest and inflicted heavy losses on the Egyptians, but its advance was halted after eight tanks were knocked out. The Israelis managed to occupy one-third of Missouri Ridge. Defense Minister Moshe Dayan countermanded orders from Sharon's superiors to continue the attack. However, the Israelis continued to expand their holdings on the west bank, by now the bridgehead was 25 miles wide and 20 miles deep.

On the northern end of the line, the Israelis attacked Port Said, opposed by Egyptian troops and a 900-strong Tunisian unit. The 162nd Armored Division, commanded by General Avraham Adan moved south and in a series of engagements decisively defeated the Egyptians, although often encountering determined resistance. The 162nd advanced towards the Sweetwater Canal area, planning to break out into the surrounding desert and hit the Geneifa Hills, where many SAM sites were located. The division’s three brigades fanned out, with one advancing through the Geneifa Hills, another along a parallel road south of them, and the third advancing towards Mina. The 217th Brigade heavy resistance from dug-in Egyptian forces in the Sweetwater Canal area, while the 406th and 500th brigades were also held up by a line of Egyptian military camps and installations, all the while being harassed by the Egyptian Air Force. The Israelis slowly advanced, bypassing Egyptian positions whenever possible. When Adan was denied air support because of two SAM batteries in the area. He ordered 406th and the 500th to attack those positions. The brigades set out from the greenbelt surrounding the Sweetwater Canal and slipped past the dug-in Egyptian infantry, moving to a point 2.5 miles from the SAM sites, and while fighting off multiple Egyptian counterattacks, they shelled and destroyed the SAMs, allowing the IAF to provide Adan with close air support. Adan's troops advanced through the greenbelt and fought their way to the Geneifa Hills, just outside the village of Mitzeneft clashing with scattered Egyptian, Kuwaiti and Palestinian troops including an armored unit. The two brigades also captured Fayid Airport, which would serve as a supply base and casualty evacuation point.

10 miles west of Bitter Lake, Colonel Natke Nir's brigade overran an Egyptian artillery brigade that had been shelling the Israeli bridgehead. Scores of Egyptian artillerymen were killed and many more taken prisoner. Meanwhile, the 252nd Division moved west and then south, covering Adan's flank and eventually moving south of Suez City to the Gulf of Suez.

On October 22 the United Nations Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 338. Largely negotiated between the US and Soviet Union, it called for the belligerents to immediately cease all military activity. The cease-fire was to come into effect 12 hours later at 6:52 pm Israeli time. Because this was after dark, it was impossible to determine where the front lines were when the fighting was supposed to stop. US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told to Prime Minister Golda Meir that he would not object to offensive action during the night before the ceasefire was to come into effect. Several minutes before the ceasefire came into effect, three Scud missiles were fired, one at the port of Arish and two at the Israeli bridgehead, one at either side, seven soldiers were killed. This was the first operational use of Scud missiles in the world. When the time for the ceasefire arrived, Sharon's division had failed to capture Ismailia and cut off the Second Army's supply lines, and also a few hundred yards short of their southern goal—the last road linking Cairo and Suez.

General Adan's drive south had left Israeli and Egyptian units scattered throughout the battlefield, with no clear lines between them. As Egyptian and Israeli units tried to regroup, regular firefights broke out. It is unclear which side fired first but Israeli field commanders used the skirmishes as justification to resume the attacks. When Sadat protested alleged Israeli truce violations, Israel said that Egyptian troops had fired first.

When the 162nd Armored Division resumed their attack on October 23, they finished the drive south, captured the last ancillary road south of the port of Suez, and encircled the Egyptian Third Army east of the Suez Canal.

Meanwhile, with the imminent arrival of UN observers to the front, Israel decided to capture Suez, assuming it would be poorly defended. An armored brigade and an infantry battalion from the 243rd Paratroop Brigade were committed to the task, the entered the city without a battle plan. The armored column was ambushed and the paratroopers came under heavy fire and many of them were trapped inside a local building. The armored column and some of the infantry force were evacuated during the day, while the main contingent of the paratrooper force eventually managed to dash out of the city and make their way back to Israeli lines. On October another ceasefire came into effect, ending the fighting, for the most part in the Sinai region. I will now shift to examining the fighting in the Golan Heights region. I avoided bouncing back on forth in a timeline way because it would have been just too confusing.

I’ve gone way over my post size limit, but this war doesn’t lend itself to quick recaps. This is all for today, next week I will finish the Yom Kippur War. Once again I hope you are enjoying these posts and maybe learning a few things.

Really great work here! I especially enjoyed the discussion regarding commitment of reserve forces, and the calculations that go into those decisions - it’s an art within an art, where the consequences of an individual decision are usually very clear, one way or the other. Good illustration of use of mutually supporting air-ground assets and tactics as well. Thanks!!