In my last post I covered the period from the end of the Yom Kippur War to early 1982. Click below if you missed it.

Today we will discuss the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Before we can examine the invasion we must first lay the groundwork and that involves looking at the Lebanese civil war and a few other incidents some of which might be familiar to you and others you may not know at all.

The factors that led to Israel's intervention were numerous and varied. The activity of the PLO and other Arab militant groups, the constant terrorist attacks and the ever-present threat of invasion were forefront in the minds of the Israeli government. When the PLO was ejected from Jordan, they just moved to Lebanon and continued on as before. As the situation in Lebanon deteriorated, it threatened to become a haven for terrorists of all shapes and kinds, all hostile to Israel. Therefore the Israelis monitored the situation in Lebanon very closely.

Lebanon was a strange place within the Middle East. It was the only country that had a large Christian population. The diversity of the Lebanese population played a major role in the lead-up to the war, as well as during the fighting. Sunni Muslims and Christians comprised the majority in the coastal cities, Shia Muslims were primarily based in the south and the Bekaa Valley in the east, and Druze and Christians populated the country's mountainous areas.

Beginnings

After Jordan lost control of the West Bank to Israel in the Six Day War, Palestinian fighters known as Fedayeen moved their bases to Jordan and stepped up their attacks on Israel and the so-called “occupied territories”. Acting like a state within a state, the Fedayeen disregarded local laws and regulations, and even attempted to assassinate King Hussein twice—leading to violent confrontations between them and the Jordanian Army in June 1970. King Hussein wanted to drive them out of Jordan, he hesitated to strike because he did not want his enemies to use the fact he was attacking Arabs or by equating the Palestinian fighters with civilians. The PLO's actions while in Jordan culminated in the Dawson's Field Hijackings of September 6.

Hussein saw this as intolerable, and ordered the army to take action. On 17 September, the Jordanian Army surrounded cities with significant PLO presence including Amman and Irbid, and began shelling Palestinian refugee camps where the Fedayeen were established. The next day, forces from the Syrian Army, with markings of the Palestine Liberation Army (The official military wing of the PLO, intervened in support of the Fedayeen and advanced towards Irbid which the Fedayeen had occupied and declared to be a "liberated" city.

On 22 September, the Syrians withdrew from Irbid after suffering heavy losses in an air-ground offensive launched by the Jordanians. Mounting pressure by Arab countries (such as Iraq) led Hussein to halt the fighting. On October 13 he signed an agreement with Arafat to regulate the Fedayeen's presence in Jordan. However, the Jordanian military attacked again in January 1971, and the Fedayeen were driven out of the cities, one by one, until 2,000 Fedayeen surrendered after they were surrounded in a forest near Ajloun July 17, marking the end of the conflict. Jordan allowed the remaining Fedayeen to leave for Lebanon.

Throughout the spring of 1975, minor clashes in Lebanon had been building up towards all-out conflict, with the Lebanese National Movement (LNM) pitted against the Phalange, and the ever-weaker national government, who was wavering between the need to maintain order and the need to cater to its constituency. On the morning of April 13 1975, unidentified gunmen in a speeding car fired on a church in the Christian East Beirut suburb of Ain el-Rummaneh, killing four people, including two Maronite Phalangists. Hours later, Phalangists led by the Gemayel family, killed 30 Palestinians traveling in the area. Citywide clashes erupted in response to this massacre.

We need to pause to understand the number of militias that will play a role in the civil war. To say that the situation in Lebanon was confused would be a massive understatement. There were nine different Maronite militias, an Assyrian Christian militia, three Sunni, three Shi’a and a Druze militia, a Kurdish militia, two Palestinian militias and two secular militias. I will quickly mention the most important ones. There were several groups that fell under the political leadership of the Christian Lebanese Front.

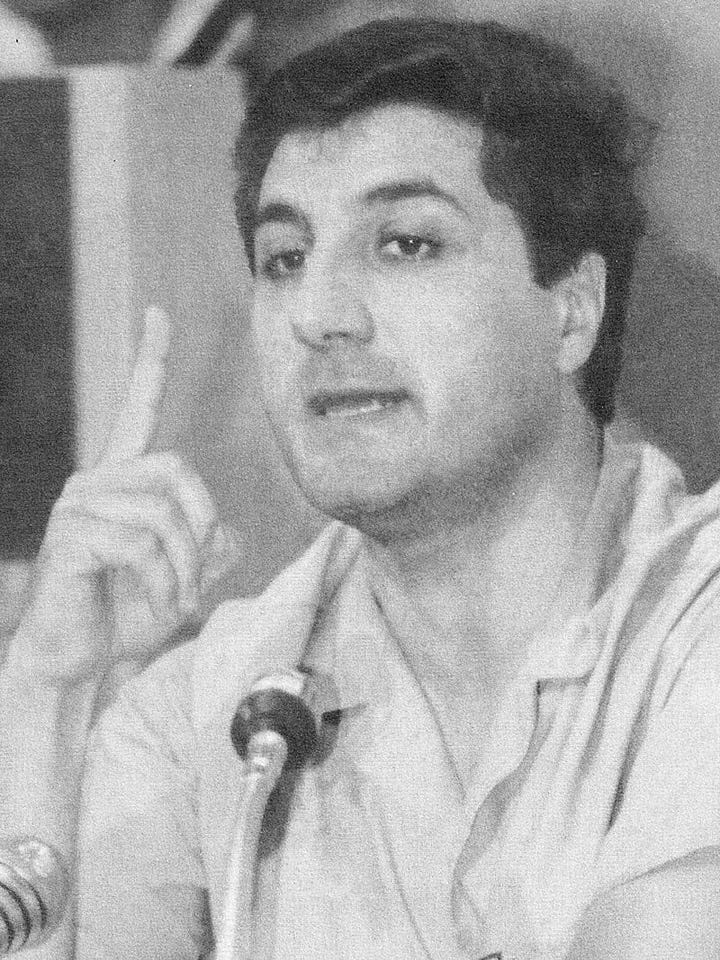

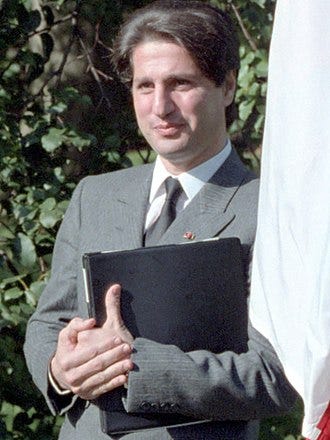

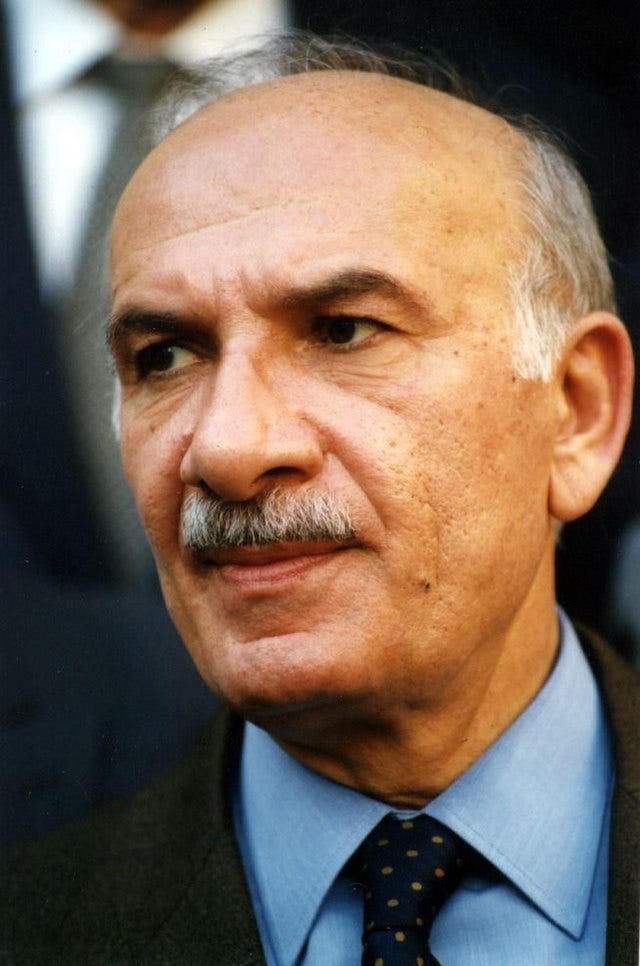

Kataeb Regulatory Forces (Phalangists): Led by William Hawi, until his death in 1976 and Bashir Gemayel until his assassination in 1982 and Amine Gemayel

thereafter. They could field 5,000 fighters. They would ultimately merge with other Maronite groups and become known as the Lebanese Forces. Phalange is the Arabic word for phalanx, a military formation used by Alexander the Great).

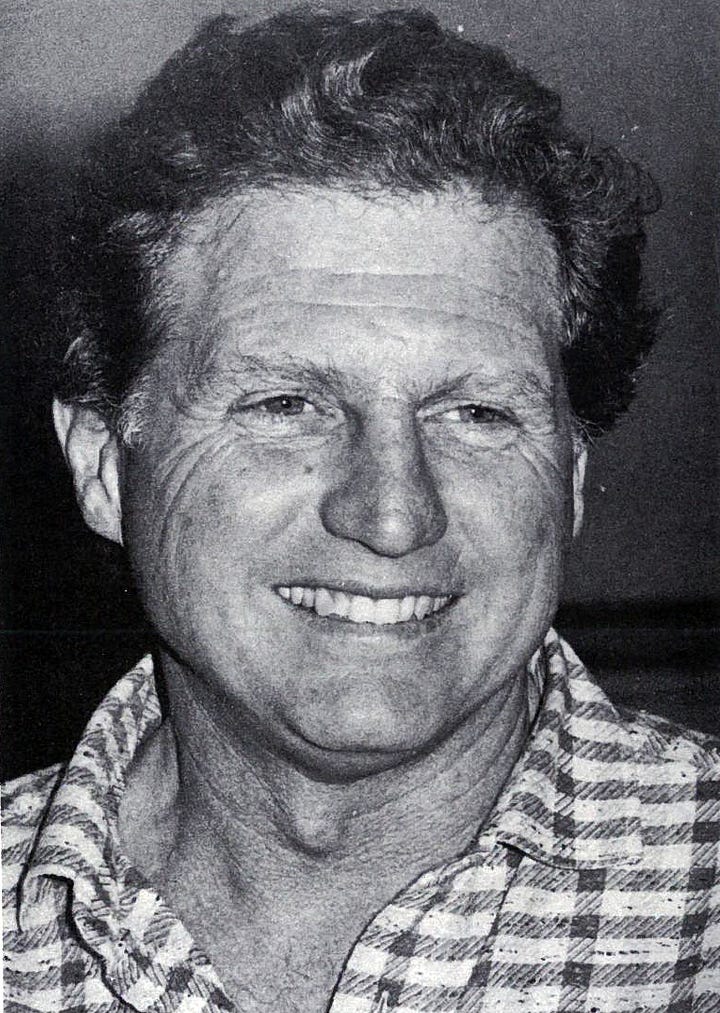

Tigers Militia (Tigers): Under the command of Dany Chamoun, another Maronite militia, which by 1978, had become the second largest force in the Christian Lebanese Front, and were able to call on 3,500 fighters.

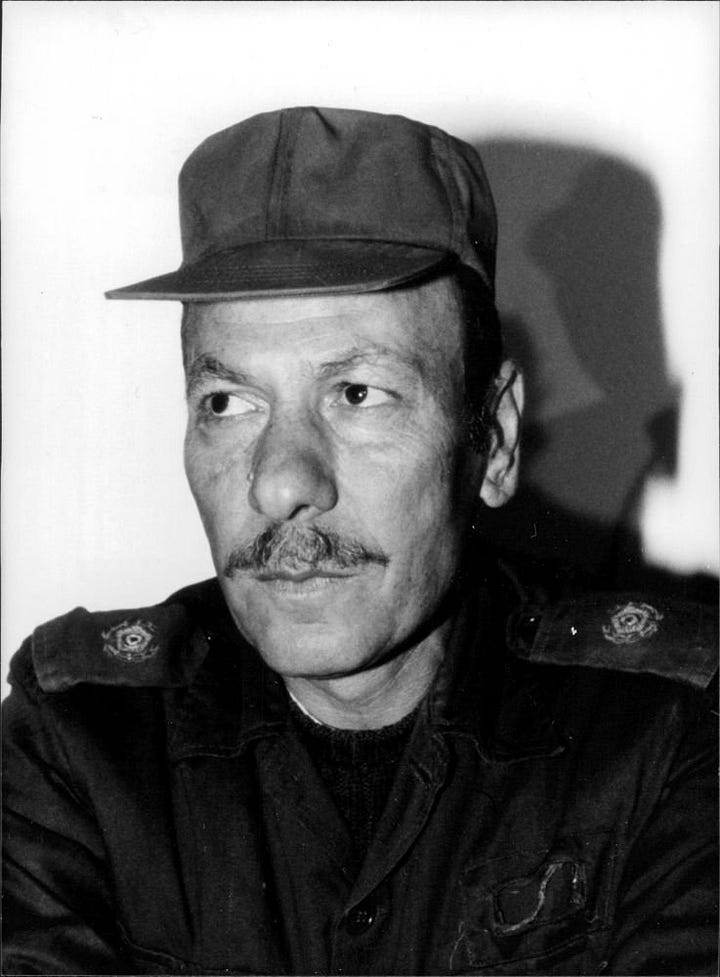

South Lebanon Army (SLA): Under the command of Lebanese Army, (the official army of Lebanon), officer Saad Haddad, basing itself in Haddad's unrecognized State of Free Lebanon. Initially, it was known as the "Free Lebanon Army" after it broke away from the Army of Free Lebanon, another Christian-dominated militia. After 1979, the SLA's activity was almost exclusively confined to southernmost Lebanon. It was comprised of 5,000 fighters.

Lebanese Arab Army: Led by Ahmed al-Khatib, the LAA was a predominantly Muslim splinter faction of the official Lebanese Army (a kind of anti-SLA). Comprised of 4,400 fighters.

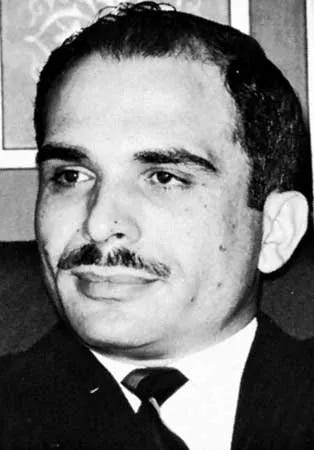

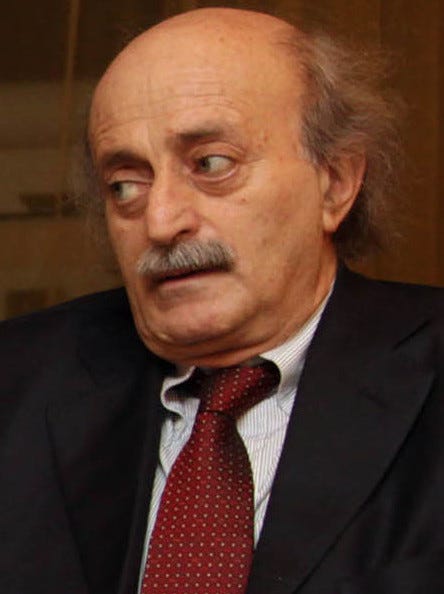

People’s Liberation Army (PLA): A Druze (a Muslim sect) militia under the command of Kamal Jumblatt until his assassination in 1977 and his son Walid Jumblatt thereafter. It was made up of 3,500 fighters and is the the military wing of the Progressive Socialist Party.

Lebanese Resistance Regiments (Amal): More famously known as Amal, which means “hope” in Arabic. Led by Musa al-Sadr until his disappearance in 1978, Hussein al-Husseini from then, until his resignation in 1980 and Nabih Berri thereafter. It is the militant wing of the Movement of the Disinherited, a Shi’a political movement. It became one of the most important Shi'a militias during the civil war, with the support of Syria. At its zenith, Amal had 14,000 troops.

Eagles of the Whirlwind: The armed branch of the Social Nationalist Party (SSNP): A Syrian nationalist party which advocates for the inclusion of Lebanon into a “Greater Syria” spanning all the countries of the Fertile Crescent. Led by Rabi Banat, their exact size is unknown but was reported to be around 6,000 fighters. They are most famous for the assassinations of Kamal Jumblatt and Bashir Gemayel.

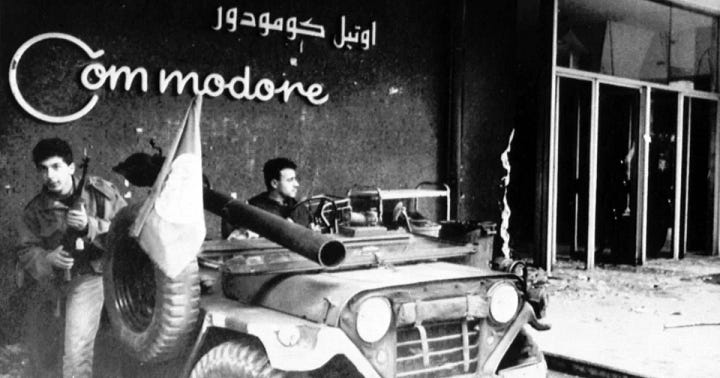

Battle of the Hotels

In October 23, 1975, with a civil war in Lebanon raging and the battle for Beruit in full swing, a group of fighters from the Muslim Independent Nasserite Movement, called the Hawks of az-Zeidaniyya, led by Ibrahim Kulaylat, occupied the Murr Tower in downtown Beruit. They had forced troops from the Christian militia, Kataeb Regulatory Force (KRF, also known as the Phalangists) to retreat, and once in control of the building, began firing rockets and mortars from the upper floors of the building into the Christian neighborhoods below. During the battle the INM had 500 fighters, however the majority of the buildings were usually defended by no more than 60 militiamen.

On October 26, the fighting in Kantari between the Muslim-leftist Lebanese National Movement (LNM) and Christian-rightist Lebanese Front militias spread to the Hotel district. The first hotel occupied was the Myrtom House, in the Rue du Mexique. Customers, including three foreign diplomats and hotel staff, were held hostage but soon released, although two hotel employees are still missing. As a counter-move, Phalangists headed by William Hawi and Bashir Gemayel began to take positions between and around the main hotels, but quickly found themselves at a disadvantage as they were under constant observation and fire from the Murr Tower. The Phalangists attempted, with little success to neutralize the Murr Tower by constant small arms fire from the Rizk Tower. On October 27, backed by homemade armored cars, the Phalangists moved in to the nearby Holiday Inn and Phoenician Hotel. At the same time fighters from the National Liberation Party’s Tiger Militia, led by Dany Chamoin, (a Maronite Christian), occupied the Saint Georges Hotel. A fierce five-day gun-battle between the INM, Phalange and Tigers ensued, which saw the Christian militias attempt to take the Murr Tower, without success. Two days later a ceasefire was called by Prime Minister Rachid Karami.

Despite the nominal ceasefire, hostilities resumed on December 8 when the LNM militias launched a major two-pronged offensive to capture Christian-held central Beirut. Units of the Lebanese Army occupied the Parliament House and central post office and blunted the Muslim drive toward the city center. However, fighting continued in the Hotel district, as the INM attacked the buildings occupied by the Christian militias. On December 8 there was a seesaw, savage close-quarter battle for the Phoenicia and Inter-Continental Hotels, and although the Phalangists were eventually forced out from some of the buildings, they managed to hold on to their main stronghold at the Holiday Inn. When the St Georges fell, the Tigers simply withdrew from the area, leaving the fighting to the Phalangists. On the same day, the Lebanese Army came to the aid of the Phalangists by launching an attack on the Phoenicia and Saint-Georges Hotel, it was successful in recapturing the Phoenicia Hotel. On December 10, it was the Muslims who were trying desperately to hold on at the Alcazar Hotel, even though parts of the building had burned to the ground.

The Phoenicia and St Georges Hotels changed hands several times during the night. Nevertheless, the Muslim militiamen were able to storm and secure the disputed Inter-Continental Hotel, and the next day they mounted another assault against the Phalangists and Lebanese National Police positions. While the Christian militiamen repulsed the attacks on their own positions, the police withdrew to the unfinished Beirut Hilton Hotel. The INM were forced out from the Saint-Georges and Alcazar Hotels after a heavy artillery bombardment by the Lebanese Army, supported by the Phalangists. Fighting came to a halt on December 12 when the exhausted combatants of both sides realized that they had more or less retained their original positions.

On 18 January 1976, an estimated 1,500 people were killed by Maronite forces in the Karantina massacre, followed two days later by a Muslims massacre in the Maronite village of Damour where 582 people were killed, by Palestinian militias. These two massacres prompted a mass exodus of both Muslims and Christians, as people fearing retribution fled to areas under the control of their own sect. The ethnic and religious layout of the residential areas of the capital encouraged this process, and East and West Beirut were increasingly transformed into what was in effect a Christian Beirut and a Muslim Beirut. Also, the number of Maronite socialists who had backed the LNM, and Muslim conservatives allied with the government, dropped sharply, as the war revealed itself to be an utterly sectarian conflict. Another effect of the massacres was to bring in Yasir Arafat and his well-armed Fatah and by consequence, the whole of the PLO, on the side of LNM.

The fighting in the Hotel district flared up again on March 17 1976. That day a combined force of fighters from the LNM, PLO and the Lebanese Arab Army (LAA), launched an all-out offensive against Christian positions in central Beirut. Then on March 21, a major assault by PLO “commando” units using armored vehicles on loan from the LAA, and supported by Muslim militias, including the Maarouf Saad Units and the Determination brigade from the INM, finally managed to dislodge the Phalangists from the Holiday Inn. Unfortunately, the militiamen got so carried away celebrating the victory, that they did not clear all the hotel rooms, which allowed Phalangists to sneak in at dawn and set up an ambush that killed a key Al-Mourabitoun commander. Having only been in control of the Holiday Inn for a few hours, the Palestinians had to do the job all over again. On March 22, LNM forces backed by PLO guerrillas, mounted a counterattack in downtown Beirut, determined to eliminate any remaining Phalangist presence west of Martyrs’ Square. Over the next two days and amid intense shelling, the Phalange were gradually pushed back to their defensive positions at Martyrs' Square and Rue Allenby. The following day, March 23, the Al-Mourabitoun recaptured the Holiday Inn and the area known as the "4th sector" or "4th district" from the Phalangists. This meant that LNM militias now dominated most of the strategic points around central Beirut. That same day marked the beginning of the battle for the port area of Beirut, just to the east of the Hotel District. LNM-PLO forces advanced towards the port sector and captured the key Starco Building. Five days later, they seized control of the Hilton and Normandy hotels. The new front line ran on an northwest to southeast axis from the Starco Building to the Hilton Hotel. Christian militia also faced attacks from Riad al-Solh Square and Nejmeh Square and Rue de Damas in the south.

Although the Christians had lost control of the Hotel district, it was not quite the end of the fighting in downtown Beirut. As the weeks went by, it was becoming painfully apparent to the Lebanese Front leadership that they were at risk of losing the war as the LNM-PLO-LAA alliance forced them to retreat farther into East Beirut. To counter this threat, the Lebanese Front finally agreed to form a "Unified Command” for the Christian militias headed by Pierre Gemayel, who issued an appeal to his supporters to rally to the defense of the Christian areas. By March 26, the KRF alone were able to mobilize some 18,000 fighters to defend the eastern sector of the Lebanese Capital and the upper Matn District easy of Beirut.

The new Christian Command felt it was imperative to retain control of Beirut's port district and began raising an elaborate defense barricade made of concrete and rubble at Rue Allenby. As the allied Lebanese Front militia forces tried to stave off the LNM-PLO assault on the port district, units of the predominantly Christian Army of Free Lebanon (AFL), another ex-Lebanese Army dissident faction led by the right-wing Maronite Christian Colonel Antoine Barakat, now entered the fray. Officers and enlisted men from the AFL's Fayadieh barracks in southeast Beirut came to the aid of their beleaguered co-religionists, bringing with them much-needed armored vehicles and heavy artillery. During the fighting, however, an artillery barrage fired by a unit under Barakat's command accidentally struck the campus of the American University of Beirut in the neighboring Ras Beirut District, causing a number of casualties among the students. The LNM-PLO advance was finally stopped on March 31 at Rue Allenby, and after Syria threatened to cut the arms shipments to the Muslim factions, both the LNM and Lebanese Front leaders agreed to a ceasefire, which came into effect on April 2. The Battle of the Hotels was over, but shortly after the battle ended, hordes of scavengers entered the building and stripped down all valuables left inside the buildings, with items such as beds, silver spoons and curtains from the Holiday Inn making their way onto Beirut’s wartime black market.

On 8 May 1976, Elias Sarkis, who was supported by Syria, defeated Suleiman Frangieh in a presidential election held by the Lebanese Parliament. However, Frangieh refused to step down. On June 1 1976, 12,000 regular Syrian troops entered Lebanon and began conducting operations against the Palestinian and other Muslim militias. This technically put Syria on the same side as Israel, since Israel had already begun to supply Maronite forces with arms, tanks, and military advisers in May. Syria had its own political and territorial interests in Lebanon, which harbored cells of Sunni Islamists and the anti-Ba’athist Muslim Brotherhood.

The next milestone in the civil war was the massacre of Tel al-Zaatar. Tel al-Zaatar was a fortified, United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, (UNRWA), administered refugee camp housing refugees in northern Beirut. The incident began in January of 1976, when Christian militias led by the Lebanese Front, as part of a campaign to expel Palestinians from northern Beirut, laid siege to the camp. There were 1,500 armed PLO fighters inside the camp at the time. They were mostly affiliated with the Vanguard for the Popular Liberation War, (otherwise known as As-Sa'iqa, a Syrian controlled militia) and the Arab Liberation Front.

There were also smaller groups of fighters from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and the PFLP-General Command. To complicate matters further, there were a number of foreign fighters present who fought under the PLO umbrella but did not support any one faction. Factionalism within the camp contributed greatly to the success of the siege, as most of the As-Sa'iqa militants and their supporters left the camp. As the siege went on the conditions in the camp deteriorated. Food, water, medical supplies and electricity were cut off to the camp.

Syrian “peacekeepers” joined the siege on the side of the Christians and added their artillery to the shelling that the Christians were already pouring into the camp. On January 22 1976, Syrian President Hafez al-Assad brokered a truce between the two sides, while covertly beginning to move Syrian troops into Lebanon under the guise of the Palestine Liberation Army, in order to bring the PLO back under Syrian influence and prevent the disintegration of Lebanon. Syria had their own reasons to join the attack. They were trying to bring both the PLO and Lebanon under their control and the elimination of the fighters in Tel al-Zaatar would be a good starting point. Despite this, the violence continued to escalate. In March 1976, Lebanese President Suleiman Frangieh requested that Syria formally intervene. Days later, Assad sent a message to the United States asking them not to interfere if he were to send troops into Lebanon. As the situation worsened, fighting resumed, the Syrians, the Phalangists and Dany Chamoin's Tigers, flattened targets inside the camp, firing around 1,000 shells a day into the camp.

An agreement was brokered between the groups by representatives of the Arab League on August 11, 1976. The combatants were assured that they would leave the camp, along with the civilians with assistance of the Red Cross. Up until this point, the Lebanese forces prevented the entry of the International Red Cross convoys, even to transport the wounded. After the ceasefire was agreed to, as the fighters were leaving the camp the PLO fighters received orders to fire upon the Christian and Syrian forces that were entering the camp to take control. The renewed attack from the PLO encouraged both Christian and Syrian forces to start killing anyone they came across. They killed old men, women and children with no regard to status as fighters or even refugee status. Yasir Arafat had encouraged those in Tel al-Zaatar to go on fighting despite the fact that they were hopelessly outnumbered and that a ceasefire had been agreed to, appealing to those in the camp to turn Tel al-Zaatar into "a Stalingrad”. Arafat hoped to maximize the number of "martyrs" and thereby capture the attention of the world. The exact number of people killed will never been known but it is thought that at least 3,000 people fell victim to the rampaging militias.

On October 9 1976, the Battle of Aishiya took place, when a combined force of PLO and a Communist militia attacked Aishiya, an isolated Maronite village in a mostly Muslim area. The Artillery Corps of the Israel Defense Forces fired 24 shells from US-made 175-millimeter field artillery units at the attackers, repelling their first attempt. However, the PLO and Communists returned at night, when low visibility made Israeli artillery far less effective and managed to occupy the village.

Also in October of 1976, Syria accepted the proposal of the Arab League summit in Riyadh. This gave Syria a mandate to keep 40,000 troops in Lebanon as the bulk of an Arab Deterrent Force charged with disentangling the combatants and restoring calm. Other Arab nations were also part of the ADF, but they lost interest relatively soon, and Syria was left in sole control, now with the ADF as a diplomatic shield against international criticism. In the south, however, the climate began to deteriorate with the gradual return of PLO combatants, who had been required to vacate central Lebanon under the terms of the Riyadh Accords.

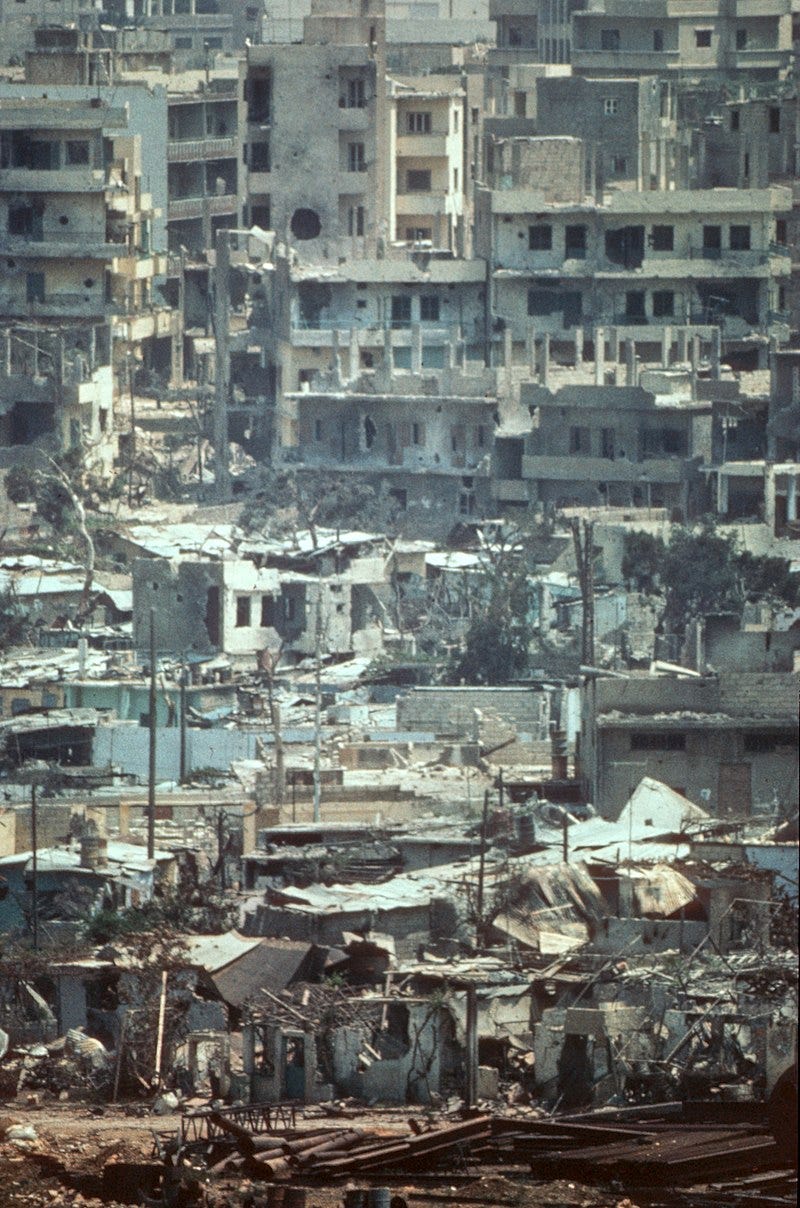

The nation was now effectively divided, with southern Lebanon and the western half of Beirut becoming bases for the PLO and Muslim-based militias, and the Christians in control of the north and East Beirut. The main confrontation line in divided Beirut was known as the Green Line.

On March 12 1977, Lebanese National Movement leader, Kamal Jumblatt was assassinated. The murder was widely blamed on the Syrian government. While Jumblatt's role as leader of the Druze Progressive Socialist Party was filled surprisingly smoothly by his son, Walid, the LNM disintegrated after his death. Although the group of leftists, Shi'a, Sunni, Palestinians and Druze would stick together for a little longer, resisting their wildly divergent interests that tore at their unity. Sensing the opportunity, Assad immediately began working on splitting up the Maronite and Muslim coalitions in a game of divide and conquer.

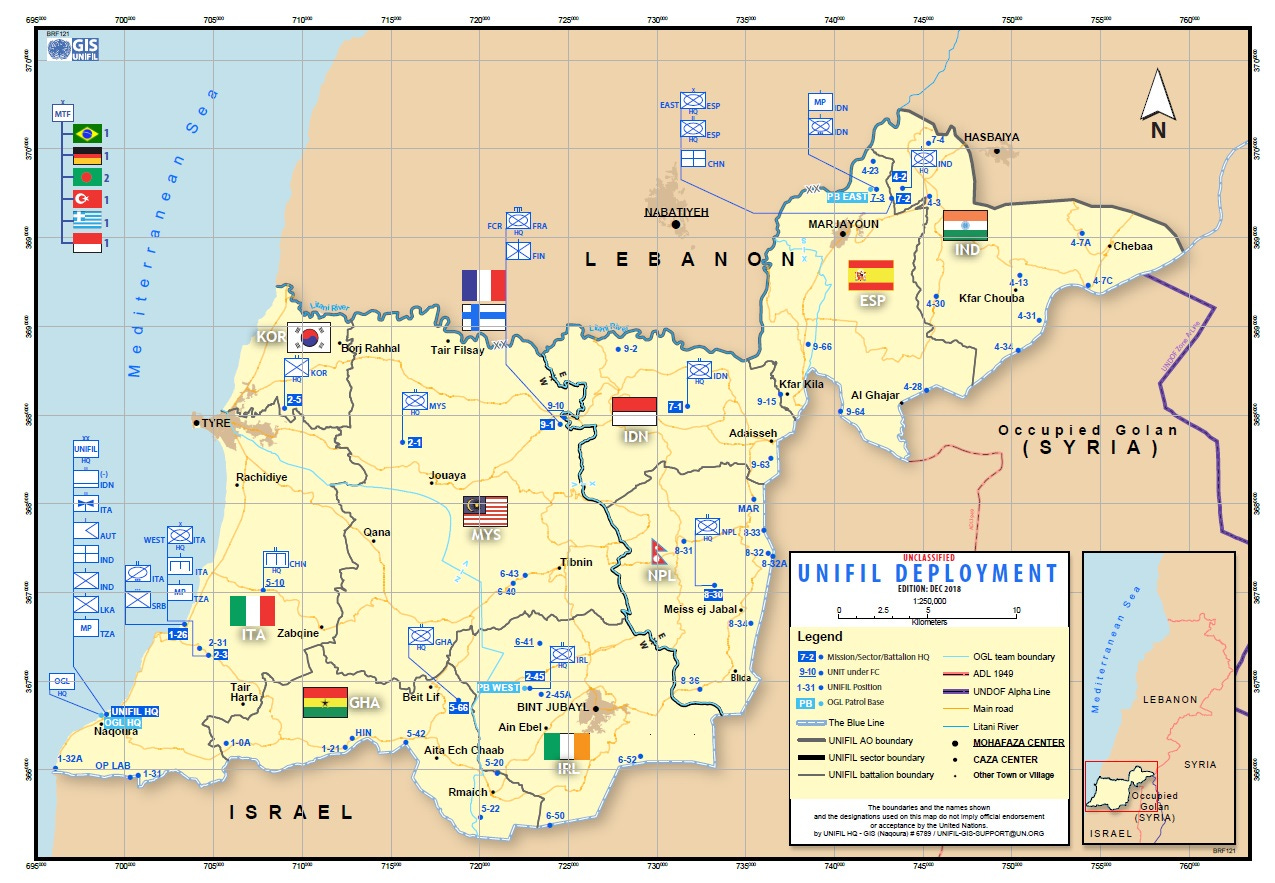

PLO attacks from Lebanon into Israel in 1977 and 1978 escalated tensions between the countries. On March 11 1978, eleven Fatah fighters landed on a beach in northern Israel and proceeded to hijack two buses full of passengers on the Haifa to Tel Aviv road, shooting at passing vehicles in what became known as the Coastal Road massacre. They killed 37 and wounded 76 Israelis before being killed in a firefight with Israeli forces. Israel invaded Lebanon four days later in Operation Litani. By the end of the operation, the IDF occupied most of the area south of the Litani River. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 425, calling for immediate Israeli withdrawal and creating the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), charged with attempting to establish peace.

Israeli forces withdrew later in 1978, but retained control of the southern region of Lebanon by managing a 12-mile wide security zone along the border. Israeli forces withdrew from Lebanon, and left it to the South Lebanon Army (SLA) to maintain this buffer zone. Israel stated that there were two reasons to support the SLA; one, to enforce the 12 mile buffer zone and to keep it clear of militants and secondly the SLA was a check to the Muslim militias still operational in South Lebanon. Prime Minister Menachem Begin compared the plight of the Christian minority in southern Lebanon (then about 5% of the population in SLA territory) to that of European Jews during World War II. The PLO routinely attacked both the Christian population and Israel, with over 270 documented attacks. People in Galilee regularly had to leave their homes during these attacks. Documents captured in PLO headquarters after the second Israeli invasion, showed the attacks had come from Lebanon. Yasir Arafat refused to condemn these attacks on the grounds that the cease-fire was only relevant to Lebanon and did not apply to the PLO. Between June and August 1979 the IDF increased its artillery bombardments and air strikes on targets in Southern Lebanon resulting in a mass exodus of civilians.

The situation went on like this for the remainder of 1979 and the beginning of 1980 and everyone knew it was only a matter of time before an incident set off the brewing tensions. On April 6 1980, clashes between UNIFIL peacekeepers and the SLA near the village of At Tiri began, when the SLA attacked Irish troops based in the village. The Irish soldiers held their ground and called in Dutch and Fijian peacekeepers as reinforcements. The battle ended on April 12 when the Dutch contingent employed TOW (Tube launched Optically tracked Wire guided) anti-tank missiles against the SLA. This ended the battle but did not end the conflicts between UNIFIL and the SLA. On April 18, a UNIFIL party set out to resupply a UN post near the Israeli border. The party consisted of three Irish soldiers an American officer, a French officer and two journalists. They were intercepted by the SLA and taken to a nearby school building and held in a bathroom, where they were interrogated. The SLA men asked all of the captives their nationalities, and singled out the three Irishmen. One of the SLA men began talking about his late brother who had been killed in the At Tiri incident. According to one of the Irish soldiers, the man talking about his brother, and another man escorted them down a flight of stairs, where the soldier was shot and left to die. The remaining members of the party left the building, with the American carrying the wounded soldier to a vehicle. One of the journalists claimed he saw the remaining Irish soldiers in the back of a car driving away. The two missing Irish soldiers were later found dead nearby. They had been shot dead and their bodies showed signs of torture.

In the summer of 1980 Bashir Gemayel was trying to consolidate all the Christian fighters under his leadership, but Dany Chamoun and his Tigers militia, the military wing of the National Liberal Party (NLP), were resisting that effort. On July 7 1980 Gemayel ordered an attack on Tigers forces near the town of Safra, north of Beirut, the attack was supposed to be conducted at around 4:00 a.m., but in order to spare the life of Chamoun, the attack was postponed to 10:00 a.m. to make sure that Dany left for Fakra. The attack claimed the lives of roughly 83 people. Ironically, prior to the attack, the leader of the NLP, (and father of Dany) Camille Chamoun, decided to disarm the militia in order to avoid further bloodshed with the Phalangists.

In late 1980 to mid 1981, Zahle, one of the largest Christian towns in all of Lebanon was the scene of a Syrian siege. Zahle was a strategic town bordering the Bekaa valley. Given Zahle's close proximity to the Bekaa Valley, the Syrian Armed Forces feared a potential alliance between Israel and the LF in Zahle. This potential alliance would not only threaten the Syrian military presence in the Bekaa valley, but was regarded as a national security threat from the Syrians' point of view, given the close proximity between Zahle and the Beirut-Damascus Highway. On April 27, Syrian troops launched an offensive against Zahle, The following day the IAF shot down two Syrian helicopters moving troops near Zahle. Despite this intervention the Syrians were able to take control of the mountain road and tighten the siege of the town. In response to the Israeli air activity, the Syrians moved SA-6 missiles into the Northern Beqaa to curtail Israeli interference.

Meanwhile, in the south, on April 19, the South Lebanon Army shelled Sidon killing sixteen civilians. Some reports stated that the attack was in response to a request from Bashir Gemayel in order to relieve the Syrian pressure on the Phalangists in Zahle.

The first six months of 1981 brought Lebanon some of the worst violence since 1976. In the South, there was an increase in clashes between Antoine Haddad’s militia and UNIFIL. This followed an agreement reached in Damascus between Lebanese President Elias Sarkis and UN officials, on the deployment of Lebanese Army soldiers into areas already occupied by UNIFIL forces. The agreement, which was reached in early March, was rejected by Haddad and on March 16, three Nigerian UNIFIL soldiers were killed by artillery fire from Haddad’s forces.

Another factor in the increased violence in this period was the political activity in Israel ahead of elections in June of 1981. Prime Minister Menachem Begin had publicly acknowledged that Israel had an alliance with Bashir Gemayel’s Phalange militia and would intervene if they were attacked by Syria. Defense Minister Rafael Eitan visited the Phalangist headquarters of Jounieh on several occasions and in South Lebanon there were regular Israeli airstrikes supporting the Phalangists around Nabatieh and the nearby Beaufort Castle.

In August 1981, defense minister Ariel Sharon began to draw up plans to attack PLO military infrastructure in West Beirut.

This is a good place to stop. In the next installment I will cover the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Once again I hope everyone is enjoying these posts and look forward to reading them. Please share them with anyone who might be interested in reading them. Until next time, Goodbye.

Chris