In my last post, I was continuing my examination of the Yom Kippur War.

It is so complicated and intricate that I need to go to three parts to keep it a manageable size for you to read. So here we go, the last part of the Yom Kippur War. When last we left, the decision had just been made for the Israelis to push into Syria.

On October 12, Israeli paratroopers from elite Sayeret Tzanhanim reconnaissance unit launched Operation Gown. Infiltrating deep into Syria and destroying a bridge in the tri-border area of Syria, Iraq, and Jordan, disrupting the flow of weapons and troops to Syria.

As the Syrian position deteriorated, King Hussein, who was under intense Arab pressure to enter the war, sent an expeditionary force into Syria. He made his intentions known to Israel through US intermediaries, in the hope that Israel would accept that this was not a move against Israel, and a reason to attack Jordan, but a move to keep Hussein in power. Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan declined to offer any such assurance, but said that Israel had no intention of opening another front. Iraq also sent the 3rd and 6th Armored Divisions with 30,000 men and 500 tanks onto Syria.

The appearance of the Iraqi divisions was a surprise to the IDF, which believed they would receive intelligence of an Iraqi move, at least 24 hours beforehand. The surprise got even bigger when the Iraqis slammed into the exposed southern flank of the advancing Israeli armor. Several advance units were forced to retreat a few miles in order to prevent encirclement. Combined Syrian, Iraqi and Jordanian counterattacks prevented any further Israeli gains. However, they were unable to push the Israelis back from the Bashan Salient, and suffered heavy losses in their engagements with the Israelis.

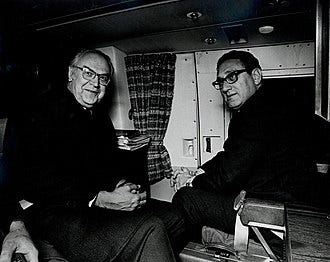

As Israeli troops began to advance on Damascus, the Soviets started to panic. On October 12, the Soviet ambassador informed US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger that his government was placing troops on alert to defend Damascus. The situation grew even tenser over the next two weeks, as Israeli forces reversed the initial Egyptian gains in the Sinai and began to threaten Cairo. The Egyptian Third Army was surrounded, and Israel would not allow the Red Cross to bring in supplies. At this point, Sadat began to seek Soviet help in pressing Israel to accept a cease-fire.

The Soviets had given their wholehearted political support to the Arab invasion and as early as October 9, they began a massive airlift of weapons, which ultimately totaled 8,000 tons of materiel. The United States had given Israel some ammunition and spare parts, but it resisted Israeli requests for greater assistance.

As the Soviets continued to pour weapons into the region, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger decided that the United States could not afford to allow the Soviet Union’s allies to win the war. Kissinger wanted to show the Arabs they could never defeat Israel with the backing of the Soviets. He also couldn’t afford to let US adversaries win a victory over an ally. By sending arms to Israel, the United States could ensure an Israeli victory, hand the Soviets a defeat, and provide Washington with the leverage to influence a postwar settlement. To that end the United States launched Operation Nickel Grass, a strategic airlift to deliver weapons and supplies to Israel during the Yom Kippur War. Over 32 days in October and November 1973, the United States Air Force’s Military Airlift Command, shipped 22,325 tons of supplies, ammunition, artillery and even tanks, in C-141 Starlifter and C-5 Galaxy transport aircraft.

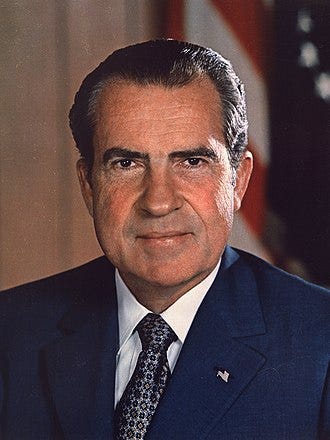

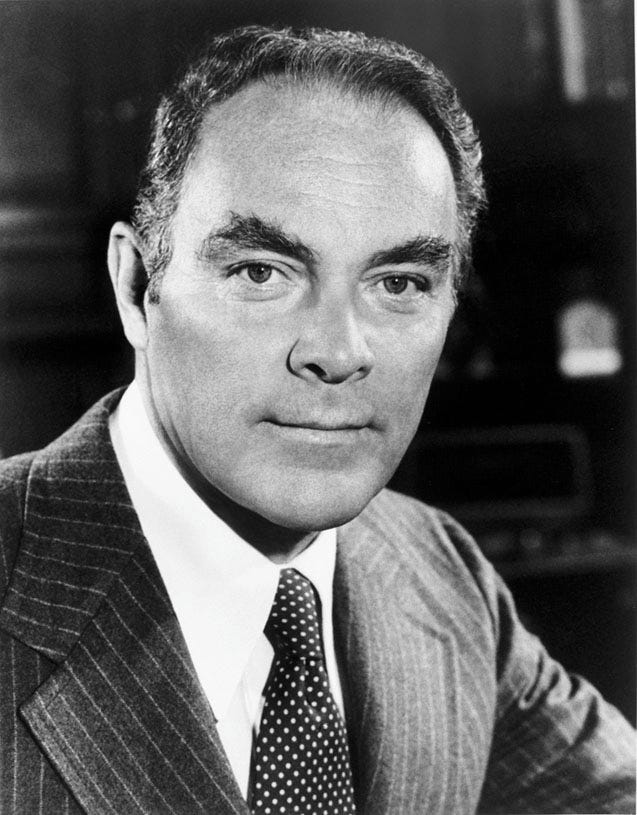

While the US was resupplying Israel, the British under Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath, imposed an arms embargo. This inhibited Israel’s ability to get spare parts for its British-made Centurion tanks. Heath also denied the US access to British bases in Cyprus to gather intelligence and would not allow British bases to be used to refuel or resupply Israel. The resupply efforts were further hampered by America’s other NATO allies who, capitulating to Arab threats, refused to allow American planes to use their air space. The one exception was Portugal, which as a consequence became the base for the operations for Nickel Grass. During the operation there were 566 flights and President Nixon asked Congress $2.2 billion in emergency aid for Israel. Following a US pledge of support for Israel on October 19, the oil-exporting Arab states within the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), followed through on their warnings to use oil as a "weapon" and declared a complete oil embargo on the United States and restrictions on other countries. This, along with the contemporaneous failure of major pricing and production negotiations between the exporters and the major US oil companies, led to the 1973 oil crisis.

On October 22, the Golani Brigade and Sayeret Matkal commandos recaptured the outpost on Mount Hermon, after a hard-fought battle that devolved into hand-to-hand combat. An IDF D9 bulldozer, supported by infantry forced its way to the peak and prepared a landing zone. Israeli paratroopers, landed by helicopter and destroyed the remaining Syrian outposts on the mountain. Seven Syrian MiGs and two helicopters carrying reinforcements were shot down as they attempted to intercede.

On October 23, a large air battle took place near Damascus during which the Israelis shot down 10 Syrian aircraft. The Syrians claimed a similar toll against Israel. The IAF also destroyed the Syrian missile defense system defending Damascus. The Israeli Air Force utilized its air superiority to attack strategic targets throughout Syria, including important power plants, fuel supplies, bridges and main roads. The strikes weakened the Syrian war effort and disrupted Soviet efforts to airlift military equipment into Syria.

On October 24, the Soviets threatened to intervene in the fighting. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reported that the Soviet airlift to Egypt had stopped and the possible reason was to change the cargo of the planes from weapons to troops. Responding to the Soviet threat, Nixon put the US military on alert, increasing its readiness for the deployment of conventional and nuclear forces. The United States was in the midst of the political upheaval of the Watergate scandal, and some people believed Nixon was trying to divert attention from his political problems at home, but the danger of a US–Soviet conflict was real.

On October 22, the United Nations imposed a ceasefire, at the request of both Israel and Egypt, dividing the Syrian General Staff over whether to continue the war. Ultimately, Syrian President Hafez al-Assad decided to de-escalate, and on October 23 Syria announced that it had accepted the ceasefire. Following the UN ceasefire, there were constant artillery exchanges and skirmishes, between the Israelis and the Syrians in the north and the Israelis and Egyptians in the south. Israeli forces also continued to occupy positions deep within Syria. According to Syrian Foreign Minister Abdel Halim Khaddam, Syria's constant artillery attacks were "part of a deliberate war of attrition designed to paralyze the Israeli economy", and were intended to pressure Israel into yielding the occupied territory. Some aerial engagements took place, and both sides lost several aircraft.

During the cease-fire, Henry Kissinger mediated a series of exchanges with the Egyptians, Israelis and the Soviets. On October 24, Sadat publicly appealed for American and Soviet contingents to oversee the ceasefire, this was quickly rejected by the White House. Kissinger also met with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin to discuss convening a peace conference with Geneva as the venue. Later in the evening of October 24, Brezhnev

sent Nixon a "very urgent" letter. In that letter, Brezhnev began by noting that Israel was continuing to violate the ceasefire and it posed a challenge to both the US and USSR. He stressed the need to "implement the ceasefire resolution” and invited the US to join the Soviets "to compel observance of the cease-fire without delay". He then threatened "I will say it straight that if you find it impossible to act jointly with us in this matter, we should be faced with the necessity urgently to consider taking appropriate steps unilaterally. We cannot allow arbitrariness on the part of Israel.” The Soviets were threatening to militarily intervene in the war on Egypt's side if they could not work with the US to enforce the ceasefire.

Kissinger immediately passed the message to White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig, who met with Nixon for 20 minutes and empowered Kissinger to take any necessary action. Kissinger immediately called a meeting of senior officials, including Haig, Defense Secretary James Schlesinger and CIA Director William Colby. The Watergate Scandal had reached its apex, and Nixon was so agitated that they decided to handle the matter without him. When Kissinger asked Haig whether Nixon should be wakened, the White House chief of staff replied firmly 'No.' Haig clearly shared Kissinger's feelings that Nixon was in no shape to make weighty decisions. The meeting produced a conciliatory response, which was sent (in Nixon's name) to Brezhnev. At the same time, it was decided to increase the DEFCON level from four to three, the highest it had been since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Lastly, they approved a message to Sadat (again, in Nixon's name) asking him to drop his request for Soviet assistance, and threatening that if the Soviets were to intervene, so would the United States.

The Soviets placed seven airborne divisions on alert and airlift capacity was marshaled to transport them to the Middle East. An airborne command post was set up in the southern Soviet Union, and several air force units were also alerted. Reports also indicated that at least one of the divisions and a squadron of transport planes had been moved from the Soviet Union to an airbase in Yugoslavia. The Soviets also deployed seven amphibious warfare vessels and 40,000 naval infantry in the Mediterranean.

The Soviets quickly detected the increased American defense condition, and were astonished and bewildered at the response. "Who could have imagined the Americans would be so easily frightened," said Nikolai Podgorny, Soviet Head of State "It is not reasonable to become engaged in a war with the United States because of Egypt and Syria," said Premier Alexei Kosygin, while KGB Chief Yuri Andropov added that "We shall not unleash the Third World War.” The letter from the US cabinet arrived during the meeting. Brezhnev decided that the Americans were too nervous, and that the best course of action would be to wait to reply. The next morning, the Egyptians agreed to the American suggestion, and dropped their request for assistance from the Soviets, bringing the crisis to an end.

After the ceasefire failed, discussions between the US and Soviet Union, yielded a new style of negotiation, called “disengagement”. Disengagement talks started on October 28, 1973, at Kilometer 101 (A spot 101 kilometers between Suez City and Cairo), between Israeli Major General Aharon Yariv and Egyptian Major General Abdel Ghani el-Gamasy. After the talks, Kissinger took the proposal that had been worked out to Sadat, who agreed with it. United Nations checkpoints were brought in to replace Israeli ones, nonmilitary supplies were allowed to pass, and prisoners of war were to be exchanged.

In December 22 1973, a summit conference opened in Geneva. All the waring parties were invited to the conference hosted by the Soviet Union and the United States, to codify a lasting peace between the Arabs and Israelis. This conference was recognized by UN Security Council Resolution 344 and was based on Resolution 338, calling for a "just and durable peace". Nevertheless, the conference was forced to adjourn on January 9, 1974, as Syria refused to attend. The conference was the first time that Arab and Israeli officials met for direct public discussions since the aftermath of the 1948 War.

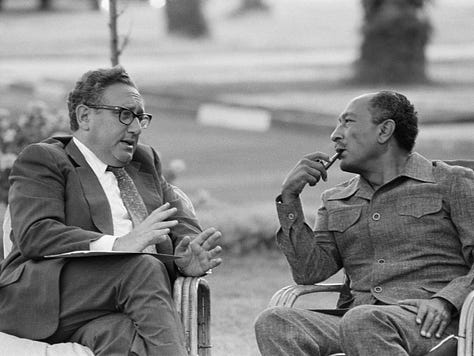

After the failed conference, Henry Kissinger flying back and forth between Tel Aviv and Cairo, taking proposals from one side to the other, soon to be known as “shuttle diplomacy”. The first real result of which was the initial disengagement agreement. It was signed by Israel and Egypt on January 18, 1974, it was officially known as the “Sinai Separation of Forces Agreement”, but more commonly called Sinai I. Under the terms of the deal, Israel agreed to pull back its forces from the areas west of Suez Canal. In addition to that pull back, the agreement also had Israeli forces pull back along the entire length of the canal, creating security zones for Egypt and the UN, each six miles wide. This was the first of many “land for peace” deals where Israel gave up territory in exchange for treaties.

On the Syrian front, where artillery duels and small skirmishes continued to occur into the spring, more shuttle diplomacy by Henry Kissinger eventually produced a disengagement agreement between Israel and Syria, signed on May 31 1974. The agreement called for an exchange of prisoners-of-war, an Israeli withdrawal to the Purple Line, and the establishment of a UN buffer zone. The UN Disengagement and Observer Force (UNDOF) was established as a peacekeeping force in the Golan.

Atrocities

In this war, as in every Arab Israeli war, there were accusations of atrocities. Unlike every other one of those conflicts, the Israelis were not the accused but were the victims. Both Egypt and Syria were accused of multiple instances of violations of the Geneva Convention.

Based on public military documents, Israeli historian Aryeh Yitzhaki estimated that the Egyptians killed about 200 Israeli POWs. In addition, dozens of Israeli prisoners were beaten and otherwise mistreated in Egyptian captivity. The order to kill Israeli prisoners came from Egyptian Chief of Staff General Saad el-Shazly Shazly, who, in a pamphlet distributed to Egyptian soldiers immediately before the war, advised his troops to kill Israeli soldiers even if they surrendered. In 2013, the Israeli government declassified documents detailing Egyptian atrocities against prisoners of war, recording the deaths of at least 86 Israeli POWS at the hands of Egyptian forces. Individual Israeli soldiers gave testimony of witnessing comrades killed after surrendering to the Egyptians, or seeing the bodies of Israeli soldiers found blindfolded with their hands tied behind their backs. Avi Yaffe, a radioman serving on the Bar-Lev Line, reported hearing calls from other soldiers saying that the Egyptians were killing anyone who tried to surrender. Issachar Ben-Gavriel, an Israeli soldier who was captured at the Suez Canal, claimed that out of his group of 19 soldiers who surrendered, 11 were killed. A second soldier claimed that another soldier in his unit was captured alive but beaten to death during interrogation. Photographic evidence of such executions exists, though some of it has never been made public. Photos were also found of Israeli prisoners who were photographed alive in Egyptian captivity, but were returned to Israel dead.

The Egyptians were by no means, alone in committing atrocities, the Syrians were even worse. In one case, advancing Israeli forces, re-capturing land taken by the Syrians early in the war, came across the bodies of 28 Israeli soldiers who had been blindfolded with their hands bound and shot in the head. In another incident, in December 1973, during an address to the National Assembly, Syrian Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass said he had awarded one soldier the Medal of the Republic for killing 28 Israeli prisoners with an axe, decapitating three of them and eating the flesh of one of his victims.

In a third incident, near the village of Hushniye, the Syrians captured eleven IDF soldiers, all of whom were later found dead, blindfolded, and with their hands tied behind their backs. Within the village, another seven prisoners were found dead, and in the nearby village of Tel Zohar, another three soldiers were found bound and shot in the head. Syrian prisoners, captured by the Israelis confirmed that their comrades had killed IDF prisoners. A soldier from the Moroccan contingent fighting with Syrian forces was found to be carrying a sack filled with the body parts of Israeli soldiers which he intended to take home as souvenirs. The bodies of Israeli prisoners who were killed were stripped of their uniforms and found clad only in their underpants, and Syrian soldiers removed their dog tags to make identification of the bodies more difficult.

When the Syrians didn't outright kill prisoners, they employed brutal interrogation techniques. Israeli POWs reported having their fingernails ripped out while others were turned into human ashtrays when their Syrian guards burned them with lit cigarettes. Others reported having electric shocks to the genitals. A report submitted by the chief medical officer of the Israeli army notes that, "the vast majority of prisoners were exposed during their imprisonment to severe physical and mental torture. The usual methods of torture were beatings aimed at various parts of the body, electric shocks, wounds deliberately inflicted on the ears, burns on the legs, suspension in painful positions and other methods.

Following the war, not only would Syria not release the names of prisoners it was holding to the International Committee of the Red Cross, they would not even acknowledge having any prisoners, despite the fact they were publicly exhibited for Syrian television crews. Since the Syrians had been roundly defeated by Israel, they were trying to use their captives as their sole bargaining chip for negotiations. One of the more well known Israeli POWs was Avraham Lanir, an IAF pilot who bailed out over Syria and was taken prisoner. Lanir died in Syrian captivity and when his body was returned in 1972, there was evidence and signs of torture.

The Naval War

Another major difference between the Yom Kippur War and other Arab-Israeli wars was the use of naval forces in the fighting. While there were always some naval involvement in the other wars, the Yom Kippur had the most by far.

On the first day of the war, Egyptian Komar class missile boats bombarded Israeli positions on the Sinai coast; targeting Rumana, Ras Beyron, Ras Masala on the Mediterranean and Sharm el-Sheikh on the Red Sea coast of the Sinai Peninsula. Egyptian frogmen raided the oil installations at Bala’eem, disabling the massive drilling rig.

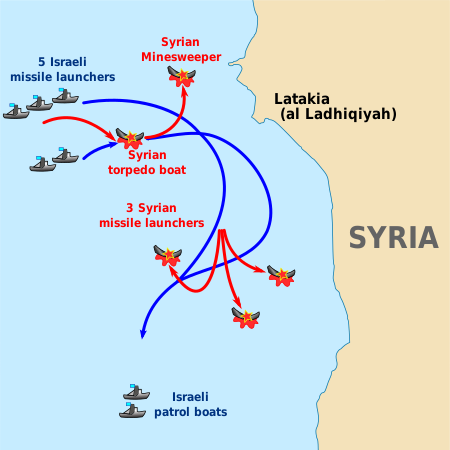

On the second day of the war, October 7, the Battle of Latakia between the Israeli and Syrian navies took place. Four Israeli Sa’ar-3 class and one Sa’ar-4 missile boats; the INS Miznak, the INS Ga’ash, INS Hanit, INS Mivtach and INS Reshef, were steaming towards the Syrian port of Latakia, when they were detected by a patrolling Syrian torpedo boat. However, the Israeli vessels encountered the torpedo boat, and an before any reinforcements could be sent, the boat was attacked and sunk with a combination of 76 mm and Gabriel surface to surface missiles. As they headed toward the shore, the Israeli ships engaged a 560-ton Syrian minesweeper and sank it with four Gabriel missiles. An hour later the Israelis made contact with three Syrian missile boats. The Israeli force turned southeast wards, and the helicopters that were accompanying them climbed high in order to see the shoreline radar stations In the meantime three Syrian missile boats, were sent northwest to attack the Israeli formation. The Syrians launched twelve Styx missiles at long range, but as the missiles approached, the Israelis employed electric countermeasures (ECM) and launched chaff (aluminized pieces of plastic that confused radar), to successfully decoy the missiles. When the Israeli ships closed the range, they fired five Gabriel missiles, sinking two of the Syrian missile boats immediately and damaging third. The surviving Syrian boat tried to escape, but ran aground in shallow water and was destroyed by cannon fire from one of the Israeli vessels. Other Syrian missile boats actually launched missiles while the boats were moored between merchant ships inside the port. However, these missiles malfunctioned or lost guidance, and two foreign (one Greek and one Japanese) merchant vessels anchored along the piers were damaged. As a result of this engagement the Syrian Navy remained bottle up in their home ports for the rest of the war.

The battle also established the Israeli Navy, long derided as the “black sheep” of the Israeli military, as a formidable and effective force in its own right. The port of Latakia was the site of another engagement between October 11, when Israeli missile boats fired into the port, targeting two Syrian missile boats spotted maneuvering among merchant ships. Both Syrian vessels were sunk, and two merchant ships were mistakenly hit and sunk.

October 7 also witnessed the Battle of Marsa Talamat. Two Israeli patrol boats cruising in the Gulf of Suez encountered two Egyptian Zodiac rubber boats loaded with Egyptian naval commandos as well as a patrol boat, all of which were backed up by coastal artillery. The Israeli boats sunk both Zodiacs and the patrol boat, although both suffered damage during the battle.

On October 9, the Battle of Baltim took place off the coast of Baltim and Damietta. Six Israeli missile boats heading towards Port Said encountered four Egyptian missile boats coming from Alexandria. In an engagement lasting a brisk forty minutes, the Israelis evaded Egyptian Styx missiles with their ECM packages and sank three of the Egyptian boats with Gabriel missiles and cannon fire. The Battles of Latakia and Baltim drastically changed the operational situation at sea to Israeli advantage.

Five nights after the Battle of Baltim, five Israeli patrol boats entered the Egyptian anchorage at Ras Ghareb where over fifty Egyptian patrol craft and armed fishing boats loaded with troops, ammunition, and supplies, bobbed at anchor. They were bound for the Israeli side of the Gulf of Suez. In the battle that followed, 19 Egyptian boats were sunk while the remaining vessel remained bottled up in port.

The Israeli Navy controlled the Gulf of Suez during the entire war. Making it possible for the Israelis to maintain a SAM umbrella over the southern end of the Suez Canal, depriving the Egyptian Third Army of air support and contributing to its encirclement.

On October 18, Israeli frogmen triggered an explosion that severed two underwater communications cables off Beruit. One cable led to Alexandria and the other to Marseille, France. As a result, all communication between the West and Syria were severed, and were not restored until the cables were repaired in late October. The cables had also been used by the Syrians and Egyptians to communicate with each other instead of radio communications that could be intercepted by the Israelis. Egypt and Syria resorted to communicating via a Jordanian radio station in Ajloun, bouncing the signals off a U.S. satellite. Commandos from the elite Shayetet 13, Naval Special Warfare Unit, were also able to infiltrate the Egyptian port of Hurghada, on seven separate occasions, destroying two vessels and the main pier. On October 16, Shayetet 13 infiltrated Port Said in two Hazir mini-submarines to strike Egyptian targets. During the raid, the commandos sank a torpedo boat, a coast guard boat, a tank landing craft, and a missile boat.

On October 11, Israeli missile boats sank two Syrian missile boats in an engagement off Tartus. During the battle, a Soviet merchant ship was hit by Israeli missiles and sank.

Having crushed the Egyptian and Syrian navies, the Israeli Navy had the run of the coastlines. Israeli missile boats utilized their 76 mm cannons and other armaments to strike targets up and down, both, the Syrian and Egyptian coasts, along the Egyptian and Syrian coastlines, including wharves, oil tank farms, coastal batteries, radar stations and airstrips, and even attacked some of Egypt's northernmost SAM batteries.

The Egyptian Navy were, able to enforce a blockade at the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, a narrow passage between Yemen an Djibouti at the entrance to the Red Sea. Eighteen million tons of oil a year was transported from Iran through the straits of Bab-el-Mandeb, through the Red Sea to the Israeli port of Eijlat. The blockade was enforced by a small Egyptian naval force, and resulted in all Israeli shipping having to be rerouted to Israel's Mediterranean ports. Because of the extreme distance the Israeli Navy was unable to challenge the blockade and the IAF had their hands full with their main mission of supporting the ground forces, to fly an interdiction mission. The Egyptians unsuccessfully attempted to blockade the Israeli coastline, and mined the Gulf of Suez to prevent the transportation of oil from the Bala'eem and Abu Rudeis oil fields in southwestern Sinai to Eilat. Two oil tankers, each carrying 2,000 tons of crude oil, sank after hitting mines in the Gulf of Aqba. Israel responded with a counter-blockade of Egypt in the Gulf of Suez. The Israeli blockade was enforced by naval vessels based at Sharm el-Sheikh and on the Sinai coast facing the Gulf of Suez. Throughout the war, the Israeli Navy enjoyed complete command of the seas both in the Mediterranean approaches and in the Gulf of Suez.

The Yom Kippur War also saw the largest direct naval confrontation of the Cold War between the United States Navy and the Soviet Navy. As the two superpowers supported their respective allies, their fleets in the Mediterranean became increasingly hostile toward each other. The Soviet 5th Operational Squadron had 52 ships in the Mediterranean, including eleven submarines, some of which carried, nuclear-tipped cruise missiles. The US 6th Fleet boasted 48 vessels, including two aircraft carriers, the USS Independence and USS Franklin Roosevelt, the USS Iwo Jima a helicopter carrier, numerous escorts and amphibious assault ships carrying 2,000 marines. As the war continued, both sides reinforced their fleets. The Soviet squadron grew to 97 vessels including 23 submarines, while the Sixth Fleet grew to 60 vessels including the USS America, (another aircraft carrier), the USS Guam (another helicopter carrier) and seven more submarines. Both fleets made preparations for war, and it was only a quick resolution of the conflict and cool heads among the two fleet commanders, that prevented a potentially disastrous battle.

Although Israeli vessels were targeted by as many as 52 Soviet-made anti-ship missiles during the war, none were sunk. The Egyptians lost seven missile boats, two torpedo boats and two coastal defense craft, while the Syrians lost five missile boats, one minesweeper, and one coastal defense vessel.

Casualties

Israel suffered 2,840 killed in action, an additional 8,800 soldiers wounded and 293 Israelis captured. Arab casualties were 15,000 Egyptians and 3,500 Syrians killed, with 23,456 Egyptians and 5139 Syrians wounded. The Iraqis had 278 killed and 898 wounded, while Jordan suffered 23 killed and 77 wounded. In addition to the casualties, there were 8,372 Egyptians, 392 Syrians, 13 Iraqis and 6 Moroccans who were taken prisoner.

Approximately 400 Israeli tanks were destroyed and 600 were damaged. They also lost 102 aircraft, half of which were shot down in the first three days of the war, however the losses were less per sortie then in the Six Day War. Arab tank losses amounted to 2,250, 400 of these fell into Israeli hands in good working order and were incorporated into Israeli service. 515 Arab aircraft were shot down and 19 Arab naval vessels, including 10 missile boats, were sunk.

Conclusions

Although the war reinforced Israel's military deterrence capability, it had a stunning and adverse effect on the Israeli public. Following their victory in the Six-Day War, the Israeli military had become complacent. The shock of the surprise attack and the initial inability to stop Arab forces at the beginning of the war, inflicted a terrible psychological blow to the Israeli public, who had not experienced a serious military challenge since 1948.

Four months after the war the Israeli public demanded an investigation into the IDF’s performance during the war. The public outcry was led by Motti Ashkenazi, the commander of Fort Budapest, the northernmost of the Bar-Lev forts, and the only that had not been captured during the war. Anger against the Israeli government (and Moshe Dayan in particular) was high. Shimon Agranat, President of the Israeli Supreme Court, was asked to lead an inquiry into the events leading up to the war and the setbacks of the first few days. The Agranat Commission published its preliminary findings on April 2, 1974. Six people were highlighted as particularly responsible for Israel's failings.

Though his performance and conduct during the war was lauded, IDF Chief of Staff David Elazar was recommended for dismissal after the Commission found he bore "personal responsibility for the assessment of the situation and the preparedness of the IDF".

Aman (Israeli Military Intelligence) Chief, Aluf Eli Zeira, and his deputy, Head of Research, Brigadier General Aryeh Shalev, were recommended for dismissal.

Lieutenant Colonel Bandman, head of the Egypt Desk for the Aman, and Lieutenant Colonel Gedelia, Chief of Intelligence for the Southern Command, were recommended for transfer out of intelligence billets.

The Agranat Commission recommended that Major General Shmuel Gonen, Southern Command Chief be relieved of command and he was forced out of the army after the publication of the Commission's final report. On January 30, 1975, the report found that "he failed to fulfill his duties adequately, and bears much of the responsibility for the dangerous situation in which our troops were caught.

Although Egypt had again suffered military defeat at the hands of its Jewish neighbor, the initial Egyptian successes greatly enhanced Sadat’s prestige in the Middle East and gave him an opportunity to seek peace. In 1978 Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin signed the first peace agreement between Israel and one of its Arab neighbors. In 1982, Israel fulfilled the 1979 peace treaty by returning the last segment of the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt.

For Syria, the Yom Kippur War was a disaster. The unexpected Egyptian-Israeli cease-fire exposed Syria to military defeat, and Israel seized even more territory in the Golan Heights. In 1979, Syria voted with other Arab states to expel Egypt from the Arab League.

Of the war’s various lessons that have been debated since 1973, four are most relevant.

First:. A military victory can be detrimental to the victorious party if it leads to complacency and stagnation. In the first phases of the 1973 war, the IDF re-fought the 1967 war. It relied heavily on the air force although it was severely constrained by the Egyptian anti-aircraft batteries, and attempted to change the course of the war by using tank formations without adequate support from infantry.

Second: Before the Six Day War, Israel’s national goals were clearly defined. Defending Israel, striving to achieve peace agreements with their Arab neighbors based on the lines of 1949 Armistice Agreement and maintaining Israel as a Jewish and democratic state. Surely, Israelis continue to support the first goal, but there was no consensus on what Israel’s final borders should be. Therefore, no consensus on how to preserve Israel as both a Jewish and democratic nation.

Third: Israel's military thinking led to a feeling of superiority and a lack of both proper intelligence gathering or planning. The Israelis sat behind their sand berm thinking that they would have plenty of warning of an Egyptian attack. All their vaunted intelligence organizations couldn't tell that the pre-war exercises by Egypt were really just a sham to lull the Israelis into a false sense of security, and it worked so well it was even beyond the expectations of the Egyptians. Even Moshe Dayan’s theory that Egypt, would not, and could not, attack Israel until it achieved parity with the Israeli air force was a strategic miscalculation.

Finally: The peace treaty between Egypt and Israel provided compelling proof that the Arab-Israeli conflict was not a zero-sum game. Losses for one side can result in losses for the other side, too, just as gains for one party can be gains for the other.

That is the end for the extremely complicated and confusing mess that was the Yom Kippur War. Next week I will run through the period between the post-Yom Kippur War to the Israeli invasion of Lebanon.

I hope you are enjoying this series and my Substack in general. If you would like to post a question or comment, subscribe to this publication, or share this post, please click the buttons below.

Great as always - please keep it just the way it is - fascinating!!