In my last post I continued my examination of the Arab-Israeli War and ended with the thought that the refugee problem is the biggest issue still unresolved after the war. Today I will give everyone a little history and a possible solution to this sticky issue. As I said in Part I of A Short History of Israel, there is no such place as Palestine and no such people as the Palestinians. I have tried to stay away from calling the Arabs living in Israel “Palestinians” but in Part V it is nearly impossible to not refer to them as that. So please bear with me and know that I haven’t changed my mind. I still believe that the refugees are Arabs not “Palestinians”.

During the Civil War in British Mandate Palestine and the 1948 Arab–Israeli War that followed, 711,000 Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes, a displacement known to them as the Nakba (catastrophe), this number does not include displaced Arabs inside Israel, where 156,000 Arabs remained in the country and became Israeli citizens. According to estimates based on an earlier census, the total Muslim population of Mandatory Palestine in 1947 was 1,143,336.

About 250,000–300,000 Arabs fled or were expelled during the 1947-1948 Civil War, before the Israeli Declaration of Independence in May of 1948. A fact which was used as the reasoning for the invasion of the Arab League states, sparking the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Many factors were responsible for the the exodus including Jewish military advances, the destruction of Arab villages, psychological warfare, fears of another massacre by Zionist militias after the Deir Yassin incident, panic after that massacre, the typhoid epidemic caused by the Israeli poisoning of wells in Arab villages, the demoralizing impact of the wealthier Arab classes fleeing, the collapse in Palestinian leadership, Arab evacuation orders, an unwillingness to live under Jewish control and direct expulsion orders by Israeli authorities.

In the first few months of the civil war, the climate in Mandatory Palestine became increasingly volatile, even though both Arab and Jewish leaders tried to limit hostilities. This period was marked by Arab attacks and Jewish defensiveness, increasingly punctuated by Jewish reprisals. The Zionist groups, Irgun and Lehi reverted to their 1937–1939 strategy of indiscriminate attacks by placing bombs and throwing grenades into crowded places such as bus stops, and markets and their attacks on British forces reduced British troops' ability and willingness to protect Jews from Arab attacks. As general conditions deteriorated, the economic situation became unstable, and unemployment grew, some Arab leaders sent their families abroad, and rumors spread that the Husseini Clan (a prominent Arab clan, which claims it's descent from the grandson of Muhammad), who’s leader at the time, was the ever popular Amin al-Husseini, were planning to bring in bands of Fellahin (peasant farmers) to take over the towns. The Arab Liberation Army (ALA) embarked on a systematic evacuation of non-combatants from several frontier villages in order to turn them into military strongholds. The largest flights of Arabs occurred in villages close to Jewish settlements and in vulnerable neighborhoods in Haifa, Jaffa and West Jerusalem. The more impoverished inhabitants of these neighborhoods generally fled to other parts of the city but those who could afford to flee further away did so, expecting to return when the troubles were over. By the end of March 1948 thirty villages saw their entire Arab population flee. Approximately 100,000 Arabs had fled to parts of the Mandate with an Arab majority, such as Gaza, Beersheba, Haifa, Nazareth, Nablus, Jaffa and Bethlehem. Arab leaders and middle- and upper-class Arab families that fled usually went to Jordan, Lebanon or Egypt.

On March 22, 1948, Arab governments agreed that their consulates in the Mandate would issue entry visas only to the sick, old people, women and children. Also in late March 1948, the Haganah Intelligence Service (HIS) reported that the Arab Higher Committee were no longer approving exit permits for fear of causing panic in the country. The Haganah was instructed by David Ben-Gurion and the Jewish Agency, to avoid spreading the panic by halting their indiscriminate attacks as well as their provocations of the British. On February 19, the only authorized expulsion at this time took place in Qisarya, south of Haifa, where Arabs were evicted and their houses destroyed. In attacks that were not authorised in advance, several communities were expelled by the Haganah and several others were chased away by the Irgun. During this period, Arab evacuees from the towns and villages left largely because of Jewish attacks or fear of impending attack, but that only an extremely small, almost insignificant number of the refugees during this early period left because of Jewish expulsion orders or forceful 'advice' to that effect. By May 1 1948, two weeks before the Israeli Declaration of Independence nearly 175,000 Arabs (approximately 25%) had already fled. The significance of the Irgun and Lehi attack on Deir Yassin cannot be understated. Meron Benvenisti, (Israeli political scientist and Deputy Mayor of Jerusalem), regards Deir Yassin as "a turning point in the annals of the destruction of the Arab landscape".

In Haifa half of the Arab community fled the city before the final battle, and another 15,000 left, apparently voluntarily, during the fighting while the rest, 25,000, were ordered to leave, by the Arab Higher Committee. However, there was no grand plan regarding this departure, and in fact Haifa’s Jewish leadership tried to convince some Arabs to stay, to no avail. On the other hand, there is clear evidence that there was, a concerted effort on the part of Haganah officials to cause Arabs to flee Haifa. Mortar attacks on Haifa on April 21 and 22 were conducted to break Arab morale in order to bring about a swift end to resistance and speedy surrender. It also had the “added benefit” of causing a major panic among the Arab population. According to witnesses three-inch mortars "opened up on the market square where there was a great crowd. A great panic took hold, the multitude burst into the port, pushed aside the policemen, charged the boats and began to flee out to sea.

Haganah, was also very successful at psychological warfare broadcasts from loudspeaker vans and radio broadcasts. Haganah Radio announced that "the day of judgement had arrived" and called on Jewish inhabitants to "kick out the foreign criminals" and to "move away from every house and street, from every neighborhood occupied by foreign criminals". The Haganah broadcasts called on the populace to "evacuate the women, the children and the old immediately, and send them to a safe haven". Jewish battle tactics were designed to stun and quickly overpower opposition. Demoralization was a primary aim, it was deemed just as important to the outcome, as the physical destruction of Arab units. The mortar barrages, psychological warfare broadcasts, and the tactics employed by infantry units were all geared to this goal. The standing orders of the Carmeli Brigade's 22nd Battalion were "to kill every adult male Arab encountered" and use fire-bombs to “set ablaze all objectives that can be set alight. From May 15, onwards, expulsion of Arabs became a regular practice.

The Israeli operations called Danny and Dekel were the start of the third phase of expulsions. The largest single expulsion of the war took place in Lydda and Ramle on July 14, 1948, when 60,000 inhabitants of the two cities were forcibly expelled on the orders of David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Rabin. In Ben-Gurion's view Ramle and Lydda constituted a special danger because their proximity might encourage cooperation between the Egyptian army, which had just attacked Kibbutz Negba, and the Arab Legion, which had taken the Lydda police station. Originally, all males in Lydda had been rounded up and secured in a compound, but after some shooting was heard, and thought to be the beginning of an Arab Legion counteroffensive, the arrests were stopped and the immediate eviction of all Arabs, including women, children, and the elderly were ordered. In explanation, Ben-Gurion said that

"Those who made war on us bear responsibility after their defeat."

Later Yitzhak Rabin wrote in his memoirs Soldier of Peace :

What would they do with the 50,000 civilians in the two cities... Not even Ben-Gurion could offer a solution, and during the discussion at operation headquarters, he remained silent, as was his habit in such situations. Clearly, we could not leave [Lydda's] hostile and armed populace in our rear, where it could endanger the supply route for the troops who were advancing eastward... Allon repeated the question: What is to be done with the population? Ben-Gurion waved his hand in a gesture that said: Drive them out!... "Driving out" is a term with a harsh ring... Psychologically, this was one of the most difficult actions we undertook. The population of [Lydda] did not leave willingly. There was no way of avoiding the use of force and warning shots in order to make the inhabitants march the 10 to 15 miles to the point where they met up with the legion.

On July 16, three days after the Lydda and Ramle evictions, the city of Nazareth surrendered to the IDF. The officer in command, a Canadian Jew named Ben Dunkelman, had signed the surrender agreement on behalf of the Israeli army along with General Chaim Laskov. The agreement assured the civilians that they would not be harmed, but the next day, Laskov handed Dunkelman an order to evacuate the population, which Dunkelman refused. In total, about 100,000 Arabs became refugees in this stage.

In the third and last period of the Arab exodus, the flight of the Arabs matched with Israeli military accomplishments. Operations Yoav, Operation El Ha-Har and Operation Hiram in October, cleared the road to the Negev, the Jerusalem Corridor and captured the Upper Galilee. Operation Horev in December and Operation Uvda in March 1949, which completed the capture of the Negev, were all met with resistance from the Arabs who would choose to flee rather than live in a Jewish state. In the Galilee it was clear to the villagers that if they left their homes, return was far from imminent. Therefore, far fewer villages spontaneously fled then in other regions.

The Six Day War, in June of 1967 initiated another wave of Arab refugees, up to 350,000 Arabs left areas that were captured by Israel, of which 145,000 had been refugees from the 1948 war. However, unlike in 1948, there was no Israeli policy to expel Arabs from captured territory. In fact there was an order given by Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, that no Arab should be ejected or expelled, either by coercion or force, from the places they currently inhabit. Arab populations fled, regardless of Israeli orders for the same reasons as the 1948 refugees did, and while most of the 1967 refugees were given permission to return by Israel, the vast majority of them did not, choosing to remain refugees because it would be better than living under Jewish rule.

An important fact to consider when viewing the “Palestinian” refugee issue is the stance of the other Arab countries in the region. Other than in Jordan, the refugees have, for the most part, been denied citizenship. In fact the Arab League instructed its members to deny the refugees citizenship. Since 1948, the status of Palestinian exiles in Arab host states has had a problematic history and even today their lives differ dramatically depending on their place of residence. In Jordan, for example, most of the 1.5 million Palestinians have citizenship and are well integrated socially and economically, although 278,678 are still living in camps. Syria, on the other hand, has maintained the stateless status of its Palestinians but has given them the same economic and social rights like enjoyed by Syrian citizens. According to a 1956 law, Palestinians are treated as if they are Syrians "in all matters pertaining to the rights of employment, work, commerce, and national obligations". As a consequence, Palestinians in Syria do not suffer from massive unemployment, and only about 111,208 refugees live in camps. However, just like Syrians citizens, Palestinians in Syria, remain under a powerful state system in which basic civil and political rights, such as freedom of expression and association, are tightly controlled, and a state of emergency, in force since 1963, grants broad, unchecked powers to a vast security apparatus. In Lebanon hundreds of thousands of Palestinians are stateless and over half live in overcrowded camps. The right to work is severely restricted, and massive poverty has become the norm. The situation of Palestinians in Lebanon deteriorated even further in the wake of the expulsion of PLO guerrillas after the Israeli invasion of 1983. According to UNRWA, of the 375,218 Palestinians, originally registered as refugees in Lebanon, only 200,000 remain, the rest have fled from the inhospitable conditions that Lebanese governments have sustained over the last two decades. However, the Lebanese stated that the Palestinians must remain stateless non-citizens because of a 1946 law that mandated governmental representation base on the religious makeup of the population. With the largest number of Greek Orthodox and Maronite Christians of any Middle Eastern state as well as a population including Druze, Shia and Sunni Muslims, it would have upset the delicate balance that is the state of affairs in Lebanon.

Initially the response of host Arab states to the incoming Palestinian refugees was to offer them refuge on the assumption that it would be temporary. When it became obvious that the problem would be a protracted one, the initial Arab sympathy became coupled with the insistence that Israel is ultimately responsible for them, and the policies of Arab states toward the refugees changed. As a result, most Arab governments strongly opposed resettlement and naturalization of the refugees. Instead, they adopted policies and procedures aimed at preserving the Palestinian identity and their status as refugees. In September 1965 the Council of Foreign Ministers of the League of Arab States formally acknowledged certain rights for Palestinians by signing the Protocol for the Treatment of Palestinians in Arab States, known as the Casablanca Protocol. This brief document called upon member states to "take the necessary measures" to guarantee to Palestinians full residency rights, freedom of movement within and among Arab countries, and the right to work on a par with citizens. But the protocol's good intentions clashed with subsequent developments on the ground. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) notes that, "as the Palestinian nationalist movement came into conflict with the governments of the Arab states, the legal status of the Palestinians diminished. As a result, few Palestinians in the Arab world now enjoy a secure right to remain in their country of residence.

After the war, following the emergence of the refugee problem. Many Arabs tried, in one way or another, to return to their homes inside Israel. For some time these practices continued to embarrass Israeli authorities until the government passed the 1954 “Prevention of Infiltration Law”, which defined, both, armed and unarmed infiltration into and out of Israel, as an offense. The purpose of the law was to prevent Arabs from returning to Israel and labeling those that did as infiltrators, subject to imprisonment and/or deportation. Between 30,000 and 90,000 Arab refugees returned to Israel over the years. They wanted to return to had been their homes prior to the war. There were also Bedouins to whom the concept of the newly established borders were foreign.

The UN, using the offices of the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization and the Mixed Armistice Commissions were involved in the conflict from the very beginning. In the autumn of 1948 the refugee problem was a fact and possible solutions were discussed. Count Folke Bernadotte said on September 16, the day before his assassination:

No settlement can be just and complete if recognition is not accorded to the right of the Arab refugee to return to the home from which he has been dislodged. It would be an offence against the principles of elemental justice if these innocent victims of the conflict were denied the right to return to their homes while Jewish immigrants flow into Palestine, and indeed, offer the threat of permanent replacement of the Arab refugees who have been rooted in the land for centuries.

Of course the Israeli government had a different take on the situation. A majority of Jews in Israel as well as the Israeli government, believe that God gave the land to Abraham 4,000 years ago and throughout all the invasions, expulsions, pogroms and holocausts there have always been Jews in Israel. Therefore they were just retaking a land promised to them, from which they had be expelled and then persecuted around the world.

On November 9 1948, the UN established the UN Relief for Palestine Refugees (UNRPR) to provide emergency relief to Palestine refugees in coordination with other UN or humanitarian agencies. Less than a month later, in response to the political aspects of the conflict, the General Assembly adopted Resolution 194, creating the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP), which in collaboration with the UNRPR, was mandated to help achieve a final settlement between the warring parties, including facilitating "the repatriation, resettlement and economic and social rehabilitation of the refugees" As well as affirming the Palestinians right to return to their homes.

Unable to resolve the "Palestine problem", which required political solutions beyond the scope of its mandate, the UNCCP recommended the creation of a "United Nations agency designed to continue relief activities and initiate job-creation projects" while an complete resolution was pending. Pursuant to this recommendation, and to paragraph 11 of Resolution 194, which concerned refugees, on December 8, the General Assembly adopted Resolution 302(IV), which established the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). The resolution was adopted and passed unopposed. It was even supported by Israel and the Arab states. UNRWA succeeded the UNRPR with a broader mandate for humanitarian assistance and development as well as the requirement for neutrality. When it began operations in 1950, the initial scope of its work was direct relief and works programs to Palestine refugees, in order to prevent conditions of starvation and distress and to further conditions of peace and stability. UNRWA's mandate was soon expanded through Resolution 393(V) (December 2 1950), which instructed the agency to establish a reintegration fund which was for the permanent resettlement of refugees and to facilitate their removal from relief rolls. A subsequent resolution, dated January 26 1952, allocated four times as much funding to resettlement than on relief, but requested UNRWA continue providing programs for health care, education, and general welfare.

According to the UNRWA a “Palestinian Refugee” is a "person whose regular place of residence was Palestine during the period of June 1 1946 to May 15 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict." The Six Day War in 1967 generated a new wave of Palestinian refugees who could not be included in the original UNRWA definition. Since 1991, the UN General Assembly has adopted an annual resolution allowing the 1967 refugees to be included within the UNRWA mandate.

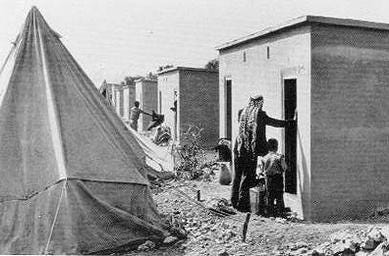

Refugee status is also passed on to the descendants of the original refugees, More than 1.4 million Palestinians still live in 58 recognized refugee camps, while there is a diaspora of 5 million Palestinians around the world. They are also the world's oldest unsettled refugee population, having been under the ongoing governance of Arab states following the 1948 war, the West Bank populations under Israeli governance, since the Six-Day War and Palestinian administration since 1994, and the Gaza Strip administered by the Islamic Resistance Movement, also known as Hamas, since 2007. The Palestinian refugees and a lack of a Right of Return for those refugees, remain major stumbling blocks to a lasting solution to this long standing problem.

What, you might say, is the solution to this ongoing problem? My idea for a solution would probably not be popular with either Israelis or the Arabs but if this problem is ever going to be solved, I think this is a good way to start. I believe that Israel is going to have to let the Arabs return to their former lands inside the country. As of 2019 the Muslim population of Israel is 1,605,700 or 17.8% of the total population of 9,021,000. If the 1.4 million Arabs currently in camps were allowed to return to their former villages it would only increase the percentage of Muslims to 29% while lowering the percentage of Jews from 74.4% to 64.4%, still a majority.

In addition to that plan I think there would need to be a confessional government like in Lebanon. A “Confessional Government” means there would be an agreement between parties to set up the government based on a fixed method of partitioning the governmental positions by religious means. In Lebanon a National Pact was signed in 1943 that outlined key points for the makeup of the government. Key points of the agreement stipulate that:

Maronite Christians would not seek Western intervention in Lebanese affairs, and accept that Lebanon was a country with Arab features.

Muslims would abandon their aspirations to unite with Syria.

The President of the Republic and the Commander of the Lebanese Armed Forces would always be a Maronite.

The Prime Minister of the Republic would always be a Sunni Muslim.

The Speaker of the Parliament would always be a Shia Muslim.

The Deputy Speaker of the Parliament and the Deputy Prime Minister would always be Greek Orthodox Christians.

The Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces always be a Druze.

There always be a ratio of 1:1 of Christians and Muslims in the Lebanese Parliament.

If they were able to arrange something like that I think it would solve most of the problem concerning the refugees. Currently Arab Israeli citizens have the same economic and political rights as any other citizen, and there are Arab members of Parliament, Arab judges, Arab cabinet members and even an Arab general in the IDF. But I think it would help tremendously if a formally written policy was put in place.

Jewish settlements are another area of contention and would need to be addressed in any plan to solve the issues facing Israel. As of January 2023, there are 144 Israeli settlements in the West Bank, twelve in East Jerusalem, in addition to 100 illegal Israeli outposts, (Settlements that are illegal even in the eyes of the Israeli government), in the West Bank. In total, over 450,000 Israeli settlers live in the West Bank and another 220,000 in East Jerusalem and an additional 25,000 Israeli settlers in the Golan Heights. The international community regards both the West Bank and the Golan Heights to be territories under Israeli occupation and the settlements established there to be illegal. In fact, in 2004 the International Court of Justice found exactly that, in an Advisory Opinion on the West Bank. If most current Jewish settlements were turned over to Arab refugees or at least, allow Arabs to live in these settlements. It would go a long way to resettling the refugees and changing international opinion in regards to Israel.

The Israeli government is already reaching out to their Arab population, who have traditionally wanted little to do with the government. For example, the IDF is making a concerted effort to recruit more Arab soldiers. One must remember that for Arab citizens of Israel military service is not compulsory like it is for the Jewish population, but in 2022 ten times as many Arabs enlisted, then in 2019. There actually an all-Arab battalion composed of 500 soldiers and the IDF is looking to expand that, as well as to begin integration of Arabs into, what would become, mixed units, comprised of Muslims, Jews and Christians soldiers. There are very good incentives for the Arabs to enlist in the IDF. First, all soldiers whether they are Jewish or not, receive two different payments after one year of service, that can be used for college, marriage, starting a business or many other things. For Arabs in particular, they receive the opportunity to get, extremely hard to come by (for anyone), building permits and land at very reduced prices (for example $10,000 for land that should cost $100,000) and enhanced job opportunities after their enlistment is over. Programs such as these are key to integrate the Arab population into Israeli society as a whole and would be doubly more important with the increased Arab population that my idea would entail.

In my next post I will look into the history of Israel starting from the end of the 1948 war. I’m not really sure how many posts this project will end up filling but I hope you are at least learning a few things if not actually enjoying them. If you would like to subscribe to this publication, leave a question or comment, or share this post, please click the buttons below.

Chris, this is great stuff - I haven’t commented previously because it was like discovering an actually great television series where you just can’t wait for next week’s episode. I especially appreciate your even-handed approach to a situation that has been so polarizing for for so long. Looking forward to the next installment - great work - keep writing!!