In my last post I covered the history of Israel during World War II, the end of the British Mandate and the Arab-Jewish Civil War. Today I will cover the actual creation of the State of Israel and its aftermath.

In the run-up to the end of the British Mandate, and in the shadow of the Arab-Jewish Civil War, there were many factors swirling around that would affect the future of the entire region. The war itself, of course, which saw 1,000 people, Jews, Arabs and British, killed and over 2,500 wounded, British fiddling while the area burned, rather than intervening in the fighting, massacres on both sides, and the cream of Arab society fleeing the area, most never to return. The British had given up long ago and were just biding their time until they could leave the area and never look back. The United Nations was still trying to find a solution to the problem but it was mostly just endless debate with no real practical proposals. Jewish officials were waiting for the expiration of the Mandate to declare their new State but were also looking for reassurances that the United States would support the declaration.

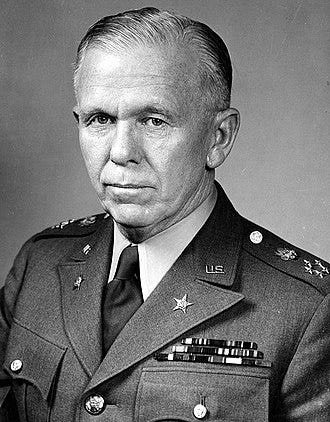

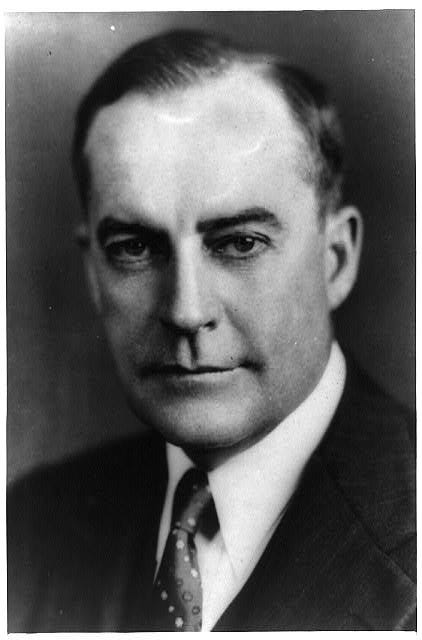

The United States was at the same time, wrestling with the question of what to do regarding that declaration. In late 1947 and early 1948 the majority of the advisors in the Truman White House, as well as the State Department, wanted the United States to stay as far away as possible from anything remotely resembling recognition for a Jewish state. The biggest opponent of recognition, was Secretary of State General George Marshall. General Marshall (He required everyone, including the President, to address him as General, rather than Mr. Secretary) thought the United States should stay out of Middle Eastern politics, even with every indication that the Soviet Union was working hard to increase its influence in the region. Marshall believed that a war in the region would be inevitable if a Jewish state was created and that war could draw both the United States and the Soviet Union into a conflict with disastrous (i.e. nuclear), consequences. He also believed that, no matter the outcome, it would be a losing proposition for the United States.

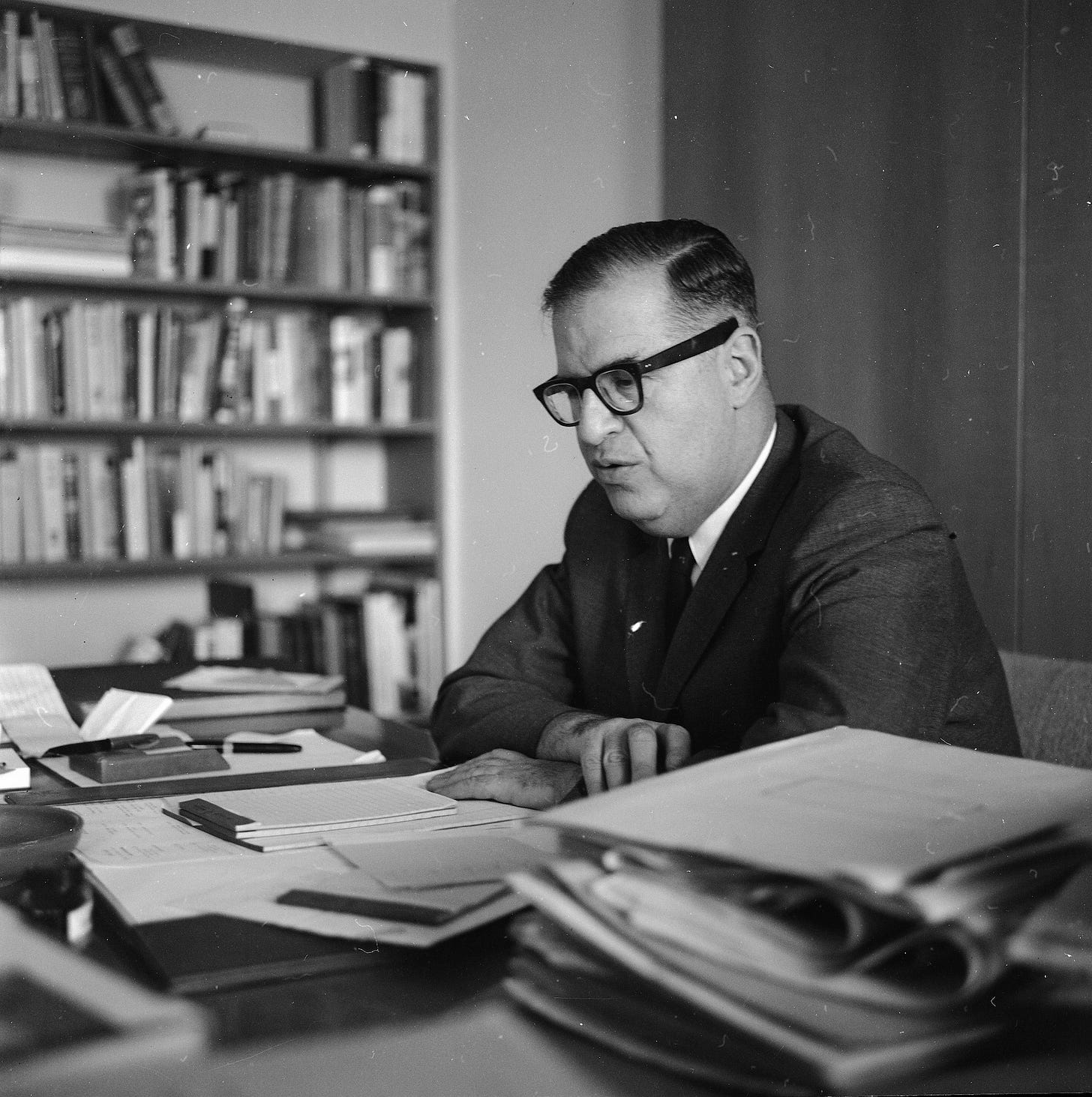

It was into this lion’s den that Moshe Sharett stepped. He was the chief representative of Jewish Agency head, David Ben-Gurion, and he had drawn the unenviable task of convincing General Marshall to support the declaration of their State. During their meeting, Marshall listened intently but at the conclusion of Sharett’s remarks, Marshall informed him that it was the position of the United States that there would no support for a Jewish State, unless it was within the framework of UN Resolution 181. Of course the Arabs had already stated their complete opposition to that resolution. No matter how much Sharett tried to persuade Marshall, he remained locked into that position. Even after President Truman made a public statement in support of a Jewish state, Marshall still opposed the idea.

On April 12 1948, three days before the end of the British Mandate, Truman had an Oval Office meeting with General Marshall and White House Counsel Clark Clifford, with Marshall arguing against recognition, and Clifford arguing for immediate recognition.

Marshall said that he believed that the position Clifford held was in an effort to garner the Jewish vote in the next election, and that domestic politics had no place in an international issue. Clifford contended that it was the Jewish-American commitment to liberal political and economic policies that would decide how that important bloc voted and that his position was one of a humanitarian nature. Clifford further argued that the unstable Middle East would receive a fresh direction with the creation of a new nation committed to democratic principles. In his book, Counsel to the President: A Memoir, Clifford described Marshall as being “red with suppressed anger as he (Clifford), presented the case for the immediate recognition of the Israeli state. Clifford wrote: “When I finished he exploded. Marshall said ‘Mr. President, I thought this meeting was called to consider an important, complicated problem in foreign policy. I don’t even know why Clifford is here.’ Truman calmly responded: “Well, General, he’s here because I asked him to be.” According to Clifford, an angry Marshall, shot back, “I fear that the only reason Clifford is here is so that he can press for a political solution of this issue. I do not think that politics should play any role in our decision.”. Marshall went on to say that he didn't believe that the Jews deserved a State, “it isn't theirs, they have stolen that land”. He went on to say “Mr. President, I'm obliged to tell you that if you should adopt the policy that is recommended by Clifford, I would be unable to vote for you in the upcoming election in November”. Before things could get any more heated, President Truman thanked both men and ended the meeting.

According to the General’s confidants, no one was ever again allowed to mention Clifford’s name in his presence. Furthermore, to ensure his words, warning against domestic politics becoming a consideration in U.S. foreign policy decisions, were remembered. Marshall entered his own account of the meeting into the State Department’s permanent record:

“I remarked to the President that, speaking objectively, I could not help but think that suggestions made by Mr. Clifford were wrong. I thought that to adopt these suggestions would have precisely the opposite effect from that intended by him. The transparent dodge to win a few votes would not, in fact, achieve this purpose. The great dignity of the office of the president would be seriously damaged. The counsel offered by Mr. Clifford’s advice was based on domestic political considerations, while the problem confronting us was international. I stated bluntly that if the president were to follow Mr. Clifford’s advice, in the next election, I would vote against the president.”

Shortly after the meeting, Marshall, who had read the room during the meeting and knew which way the President would go, spoke with Sharett and told him that “an announcement of a State was theirs (The Jews) decision to make, but don't count to the US bailing you out. We know that you have reached a historic stage and may God protect you”. Sharett, then returned to Tel Aviv to report that the United States would support an Israeli State.

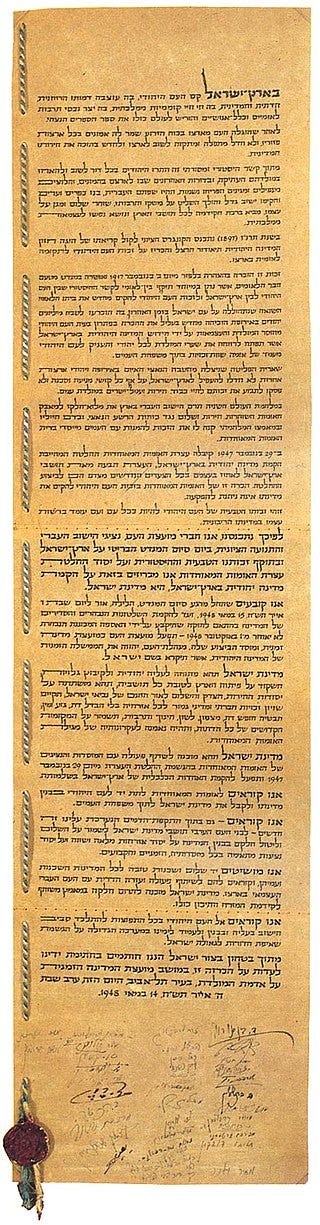

On May 14 1948 at 4:00 pm (Israel time) David Ben-Gurion spoke in front of a gathering at the Tel Aviv Museum, now known as Independence Hall. That speech was also broadcast live as the first transmission of the Kol Yisrael radio station (the current Israeli State Broadcasting Company radio affiliate). Ben-Gurion brought the meeting to order with a bang of his gavel, prompting a spontaneous rendition of Hatikvah, soon to be Israel's national anthem, from the 250 guests. After telling the audience "I shall now read to you the scroll of the Establishment of the State, which has passed its first reading by the National Council “, Ben-Gurion read out the declaration. Read the entire text here:

Taking 16 minutes to read from note cards, because the actual scroll hadn’t been finished, and ending with the words "Let us accept the Foundation Scroll of the Jewish State by rising" and calling on Rabbi Fishman to recite the Shehecheyanu blessing. After Sharett, the last of the 26 signatories, had signed, the audience again stood and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra played Hatikvah. Ben-Gurion concluded the event with the words:

"The State of Israel is established! This meeting is adjourned!"

At the same time the UN's role in Palestine was supposed to end. At 6:00 pm (New York time), The Iraqi delegate, Adnan Pachachi, strode to the speaker’s podium at the UN and reminded the General Assembly that the US delegate, Warren Austin, had said earlier, that if a solution to the Palestine problem had not be reached be 6 PM, “the game was up”. Austin meant that UN Resolution 181 would be dead and another one would need to be created to take its place. Pachachi, on the other hand, believed it meant that the way was now clear for an Arab invasion to install an Arab government over the whole of Palestine. There was one other person in the room who also thought that “the game was up” and that was UN Jewish Delegation leader Abba Eban.

He had a good reason to be upbeat about the deadline. He knew what no one else in that room knew, an independent Israel was being declared at that very moment. The Iraqi ambassador's elation was short lived because just a few minutes later Ambassador Austin received a note from the White House and approached the rostrum to make this statement:

This Government has been informed that a Jewish state has been proclaimed in Palestine, and recognition has been requested by the provisional Government thereof.

The United States recognizes the provision government as the de facto authority of the new State of Israel.

At this announcement the General Assembly chamber erupted into chaos, with many of the Islamic countries loudly voicing their indignation at the statement. The Palestinian Delegation as well as the delegations from India and Pakistan walked out in protest. While this tumult was going on, the UN Ambassador for the Soviet Union, Andrei Gromyko, stepped to the podium and stated that the Soviet Union was also recognizing Israel. Therefore in a few minutes the legitimacy of Israel, as far as the Israelis were concerned, had been settled. Over the next few days, four more countries recognized Israel; Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Uruguay. However, by then it was unknown if there would be a State of Israel for long.

On May 15 1948, at dawn, troops from Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq invaded Israel. The initial Arab plans called for Syrian and Lebanese forces to invade from the north while Jordanian and Iraqi forces were to invade from the east in order to meet at Nazareth and then to push forward together to Haifa. In the south, the Egyptians were to advance and take Tel Aviv. The mission of the Jewish forces was to survive the initial onslaught and hold the line as much as possible, even though the Arabs enjoyed major advantages (the initiative, vastly superior firepower and attacking for multiple directions at once, to name a few). As British blocking against Jewish immigrants and arms supply ended, with the end of the Mandate, the Israeli forces grew steadily with large numbers of immigrants and weapons. This allowed the Haganah to transform itself from a paramilitary force into a real army. Initially, the fighting was handled mainly by the Haganah, along with the smaller Jewish militant (or terrorist organizations depending on one’s view), groups Irgun and Lehi but on May 26 1948, Israel established the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), incorporating most of these forces into one military under a central command.

On May 18, in the south, the Egyptians attacked two settlements, Nirim and Kfar Darom, using artillery, tanks and aircraft. The Egyptians' attacks met fierce resistance and failed. On May 19 the Egyptians attacked Yad Mordechai, where a small force of 100 Israelis armed with rifles, a medium machine gun and one anti-tank weapon, held up a column of 2,500 well supported Egyptians for five days, with the Egyptians taking heavy losses. The defenders managed to buy time for the IDF's Givati Brigade to stop the Egyptian drive on Tel Aviv. From May 29 to June 3, Israeli forces battled the Egyptian as they attempted to drive north. In the first combat missions by the IAF, Israel's fledgling air force, four Avia S-199 (Ironically Czechoslovakian versions of the Nazi ME-109), fighters attacked an Egyptian armored column of 500 vehicles. The Israeli planes dropped 150 pound bombs and strafed the column. The attack caused the Egyptians to scatter, losing the initiative by the time they had regrouped. After the air attack the Egyptian forces were under constant artillery fire, and IDF patrols engaged in small-scale harassment of Egyptian lines. Following another air attack, the Givati Brigade launched a counterattack. Although the counterattack was repulsed, the Egyptian offensive was halted, as Egypt changed its strategy from offensive to defensive, and the initiative shifted to Israel.

The heaviest fighting of the war occurred between the Arab Legion of Jordan and the IDF along the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv road and in Jerusalem proper. As part of a redeployment of forces to deal with the Egyptian advance, the Israelis abandoned the Latrun fortress overlooking the main highway to Jerusalem. The Arab Legion immediately seized that, as well as the Latrun Monastery. From these positions, the Jordanians were able to cut off supplies to Israeli forces and civilians in Jerusalem.

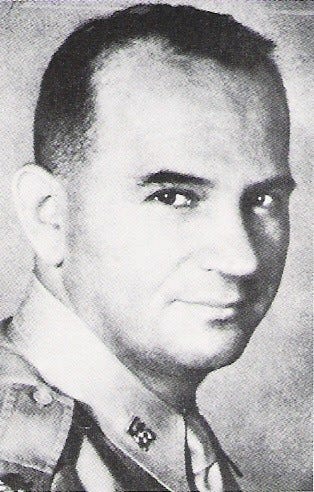

Since early 1948, Arab forces had severely restricted the supplies able to reach Jewish Jerusalem. On March 31, Dov Yosef, head of the Jerusalem Emergency Committee, introduced a draconian system of food rationing. The April Passover week ration per person was 2 lb potatoes, 2 eggs, 0.5 lb fish, 4 lb matzoth, 1.5 oz dried fruit, 0.5 lb meat and 0.5 lb matza flour. On May 12, water rationing was introduced. The ration was two gallons per person per day, of which four pints was drinking water. In June the weekly ration per person was 100 grams of wheat, 100 g beans, 40 g cheese, 100 g coffee or 100 g powdered milk, 160 g bread per day, 50 g margarine with one or two eggs for the sick. Starting on May 24, Israeli forces attempted to retake the Latrun fortress and relieve Jerusalem. In a series of battles lasting to July 18. The Arab Legion repulsed multiple attacks by the IDF. During the battles Israeli forces suffered 586 casualties, including Mickey Marcus, Israel's first general. The Arab Legion lost 90 with 200 wounded.

Jordan’s King Abdullah ordered Lieutenant General Sir John Glubb, (also known as Glubb Pasha. The English born and raised), commander of the Arab Legion, to enter Jerusalem on May 17. The Legion fired 10,000 artillery and mortar shells a day into the Jewish areas of the city and West Jerusalem was also subject to heavy sniper fire. Heavy house-to-house fighting occurred between May 19 and 28, with the Arab Legion eventually succeeding in pushing Israeli forces from the Arab neighborhoods of Jerusalem as well as the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. Several hundred of the 1,500 inhabitants of the Jewish Quarter were detained and the rest were expelled. The Jews had to be escorted out of the city by the Arab Legion to protect them against Arab mobs intent on massacre. The situation in the city was very confused, with small pockets of Jewish resistance remaining, and the Arab Legion trying to root them out. On May 19, Thomas Wasson, the US Consul-General in Jerusalem, and a member of the UN Truce Commission was shot by a sniper. He died the next day. It is not known if he was shot by an Arab or a Jew, but there was heavy activity by the Arab Legion in the area around the time he was shot.

On May 20 1948 the UN appointed Count Folke Bernadotte "United Nations Mediator in Palestine". On September 16 1948, after many consultations with both Arab and Israeli officials, Count Bernadotte issued his recommendations The proposal had seven basic premises;

Peace must return to Palestine and every feasible measure should be taken to ensure that hostilities will not be resumed and that harmonious relations between Arab and Jew will ultimately be restored.

A Jewish State called Israel exists in Palestine and there are no sound reasons for assuming that it will not continue to do so.

The boundaries of this new State must finally be fixed either by formal agreement between the parties concerned or failing that, by the United Nations.

Adherence to the principle of geographical homogeneity and integration, which should be the major objective of the boundary arrangements, should apply equally to Arab and Jewish territories, whose frontiers should not therefore, be rigidly controlled.

The right of innocent people, uprooted from their homes by the present terror and ravages of war, to return to their homes, should be affirmed and made effective, with assurance of adequate compensation for the property of those who may choose not to return.

The City of Jerusalem, because of its religious and international significance and the complexity of interests involved, should be accorded special and separate treatment.

International responsibility should be expressed where desirable and necessary in the form of international guarantees, as a means of allaying existing fears, and particularly with regard to boundaries and human rights.

The majority of Jews including the newly appointed government, initially viewed the proposal as at least a starting point for negotiations. However, the extremist group Lehi saw Bernadotte as a stooge of the British and the Arabs and therefore a serious threat to the emerging State of Israel. Lehi’s main concern was that fact that with a truce in force, Israeli leadership would agree to Bernadotte's peace proposals, which they considered disastrous. At first that was a real concern, but after debate within the Israeli cabinet they decided to reject Bernadotte’s plan and reopen hostilities. This change in plan was not communicated to Lehi and would lead to disastrous consequences later in the year.

On May 22, Arab forces attacked kibbutz Ramat Rachel south of Jerusalem. After a fierce battle in which 31 Jordanians and 13 Israelis were killed. The defenders of Ramat Rachel withdrew but fighting continued until May 26, when the entire kibbutz was recaptured. Radar Hill, a World War II British radio relay station, incorrectly identified as a radar station, was also taken and held until May 26, when the Legion recaptured it in a battle that left 19 Israelis and 2 Jordanians dead. Before the end of the war a total of 23 attempts to capture the hill were made by the Harel Brigade, all were unsuccessful.

In the Northern Sector An Iraqi force consisting of two infantry and one armored brigade, crossed the Jordan River attacking the Israeli settlement of Gesher with little success. Following this defeat, Iraqi forces moved into the strategic triangle bounded by the Arab towns Nablus, Jenin and Tulkarm. On May 25, the Iraqis were advancing towards Netanya when they were stopped by IDF forces. Four days later an Israeli attack led to three days of heavy fighting around Jenin. Iraqi forces managed to hold their positions and dug in and cessed offensive operations at which point their involvement in the war effectively ended. However, their presence tied up a large portion of Alexandroni Brigade and prevented it in assisting with other battles in the war.

On May 14, Syria invaded Israel with an infantry brigade supported by a battalion of armored cars, a company of tanks and an artillery battalion. Syrian president, Shukri al-Quwatli instructed his troops "to destroy the Zionists". The IDF was initially thrown back and David Ben-Gurion told the Israeli cabinet "The situation is very grave. There aren't enough rifles and there are no heavy weapons”. On May 15, Syrian forces turned and attacked the eastern and southern shores of the Sea of Galilee, including the villages of Samakh, Sha’ar HaGolan, Ein Gev and the fort in Tegart. They were met with heavy resistance and the attack bogged down, but on May 18, they conquered Samakh and Sha’ar HaGolan the latter of which had been abandoned to its fate. On May 21, the Syrian army was stopped at kibbutz Degania Alef by local militia reinforced by elements of the Carmeli Brigade. The remaining Syrian forces were driven off the next day by a barrage from four Israeli artillery pieces. Following their defeat at Degania Alef, the Syrians abandoned Samakh.

On May 29, the UN declared a truce. It went into effect on June 11 and was designed to last 28 days. In addition to the truce, an arms embargo was declared, with the intention that neither side would make any gains of territory or an increase of military power from the truce. Upon the implementation of the truce, the IDF had control over nine Arab cities and towns; Jerusalem (not including the Old City), Jaffa, Haifa, Acre, Safed, Tiberias, Beit She’an Samakh and Yavne Another city, Jenin, was not occupied by Israeli forces but its residents had fled. The IDF also captured 50 Arab villages outside of the boundaries of the proposed Jewish State. All told, 435 square miles of the proposed Arab State (under UN Resolution 181) were under the control of the IDF. The combined Arab forces captured 14 Jewish settlements. As well as twelve Arab villages within the boundaries of the proposed Jewish state. In addition, the Lod Airport and a water pumping station near Antipatris were under the control of the Arabs. In all, the Arab forces controlled 217 square miles of the proposed Jewish State.

At the time of the truce, the British held the view that "the Jews are too weak in armament to achieve spectacular success" but the truce "would certainly be exploited by the Jews to continue military training and reorganization while the Arabs would waste time feuding over the future divisions of the spoils". Even with an international arms embargo declared, the IDF was able to import a significant amount of arms and ammunition, including 43 fighter aircraft, the vast majority of which came from Czechoslovakia. Yitzhak Rabin, an IDF commander at the time said, “Without the arms from Czechoslovakia it is very doubtful whether we would have been able to conduct the war". The Israeli army also increased its manpower from 35,000 men to almost 65,000 during the truce, because of additional immigration into Israel and increased mobilization.

The UN truce was overseen by Bernadotte and a team of UN Observers made up of officers from the United States, Belgium, Sweden and France. His mission was to "assure the safety of the holy places, to safeguard the well being of the population, and to promote 'a peaceful adjustment of the future situation of Palestine”. After the UN truce was in place, Bernadotte began to address the issue of achieving a political settlement. The main obstacles in his opinion were "the Arab world's continued rejection of the existence of a Jewish state, whatever its borders, and Israel's policy, based on its increasing military strength, of ignoring the partition boundaries and conquering as much territory as it could, as well as the emerging Palestinian Arab refugee problem". Taking all these issues into account, Bernadotte presented a new partition plan. He proposed that the Palestinians be integrated with Jordan and that a union between Israel and Jordan be established. He proposed that part of the Negev be included in the Arab state and part of Western Galilee be included in Israel, that all of Jerusalem be part of the Arab state, but, with the Jewish areas enjoying autonomy within the city, and that Lydda Airport and Haifa be free areas belonging to neither Israel or Jordan. Israel rejected the proposal, especially the aspect of losing control of Jerusalem, but they did agree to extend the truce for another month. However, the Arabs rejected both the extension of the truce and the whole proposal.

The truce would almost last the intended 28 days but fighting resumed and the situation would remain confused and chaotic. In my next post I will write about the rest of the war and its aftermath. If you are enjoying these posts please consider sharing them with others and if you haven’t already, please subscribe or leave a comment.