Thank you for joining me for Part IV of the reposting of my series on the history of Israel. This is the last reposting of these articles I’m going to do, you can go into the archive and read the other 19 parts if you would like. My next post will be about the Palestinian refugee issue, coming out on Tuesday. I hope you have been sharing these with as many people as possible. The truth of this conflict needs to be brought into the light, and the lies of the terrorists and the media need to be refuted.

In my last post I covered the end of the British Mandate, the Israeli declaration of independence and the beginning of the Arab-Israeli War. Today I will cover the remainder of the war and its aftermath.

Since I reference all the IDF units by their names I thought this would be a good time to go over the composition of the IDF, it was organized into twelve brigades with most of them having place names rather than number designations.

Golan Brigade commanded by Moshe Mann with a strength of 3,166.

Carmeli Brigade commanded by Moshe Carmel with a strength of 2,000.

Alexandroni Brigade commanded by Dan Even with a strength of 5,200.

Kiryati Brigade commanded by Michael Ben-Gal with a strength of 1,400.

Givati Brigade commanded by Shimon Avidan with a strength of 5,000.

Etzioni Brigade commanded by David Shaltiel with a strength of 3,600.

7th Armored Brigade commanded by Shlomo Shamir with a strength of 40 tanks and 2,000 men.

8th Armored Brigade commanded by Yitzhak Sadeh with a strength of 40 tanks and 2,000 men.

Oded Brigade commanded by Avraham Yoffe with a strength of 1,500.

Harel Brigade commanded by Yitzhak Rabin with a strength of 1,400.

Yiftach Brigade commanded by Yigal Allon with a strength of 4,500.

Negev Brigade commanded by Nahum Sarig with a strength of 2,400

Before starting research on the history of Israel, I thought that the 1948 war was a time of solidarity between the different factions of the new state. I was surprised to find that not only was there not consensus but there was outright conflict between the groups that made up Israel at that time. A good example of this would be the story of The Altalena, an incident that almost caused a civil war, right in the middle of the fight to establish Israel.

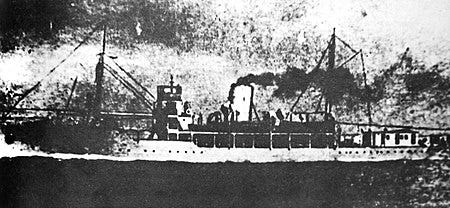

When the fighting began in May of 1948, Irgun and Lehi, the extremist groups whom had been fighting since 1940, were fighting separately from the IDF. They were negotiating with the newly minted IDF about what units would be excepted into the army and what roles those units would play. Because of their separate command structure, the two groups were making private arms purchase for their fighters. One of those purchases, made by Irgun from the French, consisted of 5,000 rifles, 250 light machine guns, 3,000 artillery rounds, 50 bazookas, 10 Bren Carriers and five million rifle rounds. The cargo was loaded on the former US landing craft, LST-138, captained by ex-US Navy lieutenant Monroe Fein and rechristened The Altalena. Along with 900 Jewish volunteers, the ship left France on June 11, the day the first UN brokered truce began. As the ship made its way to Israel, the head of Irgun, Menachem Begin, attempted to negotiate the fate of The Altalena's cargo with David Ben-Gurion. Eventually it was agreed that 20% of the cargo would go to Irgun and the rest of it would be given to the IDF. However, as the ship neared Israel, Ben-Gurion and the Israeli cabinet changed their minds and decided they wanted the entire cargo. Orders were given to Dan Even of the Alexandroni Brigade to move troops to Kfar Vitkin, the ultimate destination of the ship, and demand that Begin give up the entire cargo. The Altalena reached Kfar Vitkin in the late afternoon of June 20, and was met by Menachem Begin and a group of Irgun members on the beach. Irgun sympathizers from the nearby town of Netanya and a neighboring village gathered on the beach to unload the cargo. 2,000 rifles, two million rounds of ammunition, 3,000 shells, and 200 Bren light machine guns were unloaded and lying on the sand when Even and his men arrived and presented Begin with the ultimatum to give up the cargo. He was told that if did not hand over the cargo, it would be taken by force. Begin said he needed more time and drove to Netanya to consult with government officials. Failing to reach an accord with the government, Begin returned to the beach and conferred with his officers. As evening began, rifle fire broke out, which side fired first is a matter of dispute. As the fighting began, Begin fled to the Altalena in a rowboat. On shore, the Irgun fighters were quickly forced to surrender. The IDF suffered two dead and six wounded, while Irgun suffered six dead and eighteen wounded. In order to prevent further bloodshed, the residents of Kfar Vitkin held negotiations between Begin’s deputy, Yaakov Meridor, and Dan Even, they ended in a general ceasefire and the transfer of the weapons already on shore to the local IDF commander.

Meanwhile, Begin ordered the Altalena to sail to Tel Aviv, where there were more Irgun supporters. Many Irgun members, who had joined the IDF earlier that month, left their bases and assembled on the beach to meet the vessel and rumors began circulating that the Irgun was planning a coup. The Altalena was shadowed by Israeli navy corvettes on its trip to Tel Aviv. As the ship neared the coastline, the corvettes began firing bursts of machine-gun fire but the ship did not turn back. The Altalena arrived at midnight on June 21, beaching itself at the foot of David Frischmann Street, in view of locals, journalists, and UN observers watching from the terrace of the Kaete Dan Hotel. Ben-Gurion ordered Yigael Yadin (Chief of Staff) to concentrate a large force on the Tel Aviv beach to take the ship by force. He also indicated that he would order the Israeli Navy to stop any attempt by The Altalena to retreat into international waters. Parts of the Harel and Yiftach Brigades were moved into the area with their artillery and Begin was ordered to surrender. The next day, when he had not still not responded to the surrender order, Ben-Gurion ordered the shelling of the Altalena. Begin, who was hoping to avert civil war, ordered his men not to shoot back, and raised the white flag over the ship. However, the firing continued, and some Irgun men on board reportedly returned fire.

Yitzhak Rabin the the IDF commander on the beach said that one of the shells hit the ship, and it began to burn. Yigal Allon, the Yiftach Brigade commander, later claimed five or six shells were fired as warning shots and the ship was hit by accident. IDF troops on the shore also directed small-arms fire towards the ship, including heavy machine guns with armor-piercing rounds. Some soldiers refused to open fire on the Altalena, including a soldier whose brother, an Irgun officer, was on the ship.

On the beach, a battle between the IDF and Irgun forces along the shore erupted, and clashes between IDF and Irgun units also took place throughout Tel Aviv. Although civil war appeared imminent, a cease-fire was arranged by the evening of June 22. Meanwhile, Begin reached his clandestine radio station and ordered his men not to fight back. He called for them to assemble in Jerusalem and continue the battle for the Old City. Mass arrests were carried out against Irgun soldiers who had taken part in the fighting. Irgun units in the IDF were disbanded, and their soldiers dispersed among other units. Sixteen fighters along with three IDF soldiers were killed in the incident. In all, more than 200 Irgun members were arrested. Most were released several weeks later, with the exception of five senior commanders who were detained for two months. Eight IDF soldiers who refused to fire on the Altalena were court-martialed for insubordination.

Meanwhile, the situation in besieged Jerusalem was becoming more grave by the day. Dov Yosef and the Jerusalem Emergency Committee knew that of something wasn’t done soon to relieve the city, people would start to starve to death. They estimated that seventeen tons a day were needed to keep the city going but near the end of May, only one ton a day was getting through. Eventually the city was saved via the opening of the so-called Burma Road, a makeshift bypass road built over a goat path, by Israeli forces that allowed supply convoys to bypass the Arab cordon and enter Jerusalem. On May 30, supplies carried by porters had begun passing through the area and the first vehicle convoy passed through on the night of June 1. During the construction the Jordanians spotted the activity and attempted to shell the road, but because it was below the level that their guns could fire, the shelling was ineffective. However, Jordanian sharpshooters killed several road workers, and in an attack on June 9 eight Israelis were killed. The road was finally completed on June 14, and by the end of June the convoys delivered 100 tons of supplies a night. The Burma Road remained the sole supply route for several months.

On July 7, a day before the expiration of the truce, Egypt renewed the war by attacking Negba a strategic kibbutz in the southern Negev desert. This opened a short period between UN cease-fires known as the “10 Days of Battle”. Egyptian forces surround the village to prevent outside Israeli intervention and after a heavy artillery barrage, attacked from three directions. The simultaneous Egyptian attacks were poorly coordinated, and their infantry and armor did not work well together. Negba's defenders held out, although the initial effort reached a distance of 55 yards from the perimeter. The Egyptians regrouped and attempted a final thrust from the north, achieving no success, the Egyptians retreated. Israel subsequently used Negba as a base for future operations in an attempt to cut through the Egyptian lines and link up with the Israeli-held enclave in the northern Negev. This battle is considered to be the turning point on the southern front.

On the night July 8, the Givati Brigade launched Operation An-Far, an attack to gain control of the approaches to southern Judea and block the advance of the Egyptian army. The fighting continued until July 15, and while the Israelis managed to achieve limited success in the operation, especially in clearing their flanks, it failed to achieve the main objective—linking up with the forces in the Negev desert, this caused Operation Death to the Invader to be mounted. While the Israelis were successful in several attacks, most notably in Hatta and Karatiyya, the main objective of linking up the Negev and Givati areas still was not realized, and going into the second truce, the Negev villages remained an Israeli enclave surrounded by Egyptian positions. However, the capture of Hatta and Karatiyya, to the south of the Majdal/Bayt Jibrin road, forced the Egyptians to create a supply road of their own across the desert between Suwaydan and al-Fallujah. The operation ended the period of the war between the first and second ceasefires, with few territorial changes in the south. According to the Egyptian commander in the region Ahmed Ali al-Mwawi, the situation at the end of this period for the Egyptian army was not good, owing to a lack of ammunition, coordination and morale.

On July 10, Operation Danny began, it aimed to secure and enlarge the corridor between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv by capturing the roadside cities Lod (Lydda) and Ramle. In the second stage of the operation the fortified positions of Latrun, overlooking the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway, and the city of Ramallah were also to be captured. Lydda had become an important military center in the region, lending support to Arab military activities elsewhere, and Ramle was one of the main obstacles blocking Jewish transportation. Lydda was defended by a local militia of 1,000 and an Arab Legion contingent of 300, the IDF forces attacking the city numbered 8,000. The city was attacked from the north and captured on July 11. 450 Arabs and ten Israeli soldiers were killed.

The next day, Ramle fell. The civilian populations of Lydda and Ramle fled or were expelled and sent to the Arab front lines. In Lydda, the population was expelled without transportation, forcing a large portion of the population to walk to the Arab village of Barfiliya, ten miles away, in temperatures around 95 degrees. No one is sure how many Arabs died on the march, estimates range from a dozen to 350. Either way the expulsion of Ramle and Lydda constituted the biggest expulsion of the war, accounting for one-tenth of the Arab population that was removed.

Operation Kedem was an operation to secure the Old City in Jerusalem, but few resources were allocated to the operation. It was originally to begin on July 8, with attacks by Irgun and Lehi fighters. However, it was delayed by the commander of the Etzioni Brigade, David Shaltiel, because he did not trust their ability after the Deir Yassin incident. The plan was for Irgun forces commanded by Yehuda Lapidot to break through at the New Gate, while Lehi was to break through the wall between the New Gate and the Jaffa Gate with the Beit Horon Battalion of Shaltiel’s brigade, striking west from Mount Zion. The battle was scheduled to begin on July 16, at 8 PM during Shabbat. The attack was postponed twice, first to 11 pm then to midnight and didn’t actually begin until 2:30 am. Irgun managed to break through at the New Gate, but the other forces failed in their missions. At 5:45 am on July 17, Shaltiel ordered a retreat. On July 18, elements of the Harel Brigade took ten villages to the south of Latrun to enlarge and secure the area of the Burma Road.

In the Galilee area, two operations were mounted. Operation Dekel was an attempt to take the lower Galilee and Nazareth, while Operation Brosh aimed to dislodge Syrian forces from the Eastern Galilee and the Benot Yaakov Bridge. Operation Brosh was a failure but Nazareth was captured on July 16, and by the time the second truce took effect, the whole area from Haifa Bay to the Sea of Galilee had been captured.

On July 18, 1948 at 7 PM a second UN brokered truce came into effect. This time there was no scheduled end to the truce, it was supposed to hold as long as possible. However there were violations on both sides.

One violation involved the Arab villages south of Haifa known as the “Little Triangle”. These villages, which were being supplied by Iraqis from northern Samaria, repeatedly fired at Israeli traffic along the main Tel Aviv-Haifa road. The poorly planned Israeli assaults on June 18, and July 8, had failed to dislodge the Arab militia from their positions, and the Israelis launched Operation Shoter on July 24. The objective was to gain control of the road to Haifa and destroy all enemy forces in the area. Israeli assaults on the 24 and 25 of July were beaten back by stiff resistance. Launching another assault, this time backed up with heavy shelling and aerial bombing, the infantry was able to break through the Arab lines. Three Arab villages surrendered, most of the inhabitants fled either before or during the attack and hundreds were forcibly expelled during the following days. Following the operation, the Tel Aviv-Haifa road was open to Israeli military and civilian traffic, as was traffic along the Haifa-Hadera coastal railway.

As I mentioned in the last post, on September 16, Count Folke Bernadotte proposed a new partition for Palestine. The UN would control and regulate Jewish immigration. The Negev would be divided between Jordan and Egypt, and Jordan would annex Lydda and Ramle. The whole of Galilee would be part of a Jewish state, with the frontier running from Al-Faluja northeast towards Ramle and Lydda. Jerusalem would be internationalized, with municipal autonomy for the city's Jewish and Arab inhabitants. The port of Haifa and Lydda Airport would be free areas with neither side in charge. All Arab refugees would be granted the right of return, and those who chose not to return would be compensated for lost property. The plan was quickly rejected by both sides for a host of reasons.

As this this partition plan was being discussed, Lehi was still concerned that the plan would be accepted and the gains made in the war so far would be given up. Lehi leadership decided that the only course of action was the assassination of Bernadotte. The killing was approved by the three-man 'center' of Lehi: Yitzhak Shamir, Nathan Yellin-Mor and Yisrael Eldad.

On September 17, Yehoshua Cohen and three other Lehi fighters set up a makeshift roadblock at Ben Zion Guini Square, off Hapalmach Street in Jerusalem and waited for Count Bernadotte’s motorcade to approach. When it did, three members of the Lehi team approached the convoy. Captain Moshe Hillman, the Israeli liaison officer, who was sitting in the lead UN vehicle, called out in Hebrew to let them through, but was ignored. Cohen came up to Bernadotte's car, raised a Thompson submachine gun and fired through an open window. Bernadotte was hit with six shots and 18 rounds hit Colonel Andre Serot, a French officer attached to the UN. Serot was killed instantly and Bernadotte died a few minutes later at a hospital. The four shooters escaped and were never caught or tried for the murders. Many years later Yehoshua Cohen who was terminally ill, admitted he was the man who had pulled the trigger and killed Count Folke Bernadotte and Serot.

On September 22 1948, before any permanent peace plans could be put in place, the Provisional State Council of Israel passed the Area of Jurisdiction and Powers Ordnance. The law officially annexed all the land Israel had captured since the war began. It also declared that from then on, any land captured by the Israeli army would automatically become part of Israel.

Not only were there military units from Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Egypt, Iraq and Israel but there were also Arab militias involved in the fighting. One was a unit called the Arab Liberation Army (ALA), led by Fawzi al-Qawugji. He had also fled to Nazi Germany during World War II. But unlike our old friend, al-Husseini, who had just been a pawn of the Nazis, al-Qawugji had actually been a member of the Wehrmacht. He attempted to recruit 10,000 fighters for the ALA, but by mid-March 1948, had only reached 6,000 and never increased much beyond that figure. Its ranks included Palestinians, Syrians, Lebanese, and a few hundred Iraqis, Jordanians and Arabs who had joined the Muslim Brothers from Egypt as well as Germans, Turks and even British deserters. The other force was called the Army of the Holy War and was commanded by Hasan Salama with a strength of 10,000 foreign fighters and Palestinian Arabs.

On October 22, a third truce went into effect but was not recognized by the irregular Arab forces, who continued to harass Israeli forces and settlements in the north. On the same day that the truce came into effect, the Arab Liberation Army violated it by attacking the Northern Israel settlements of Manara, Misgav Am and Shekih Abe. They were able to capture Skekih Abe and repulsed counterattacks by local Israeli units and ambushed Israeli forces attempting to relieve Manara. Misgav Am and Manara were totally cut off, and Israel's protests to the UN, about the violation of the truce, failed to change the situation.

On October 24, the IDF launched Operation Hiram to capture the entire Upper Galilee area and drive the ALA into Lebanon. During the operation the three brigades tasked to the operation; the Carmeli, the Golan and the Oded Brigades under overall command of Moshe Carmel, completed the objectives in under 60 hours and managed to ambush and destroy an entire Syrian battalion as well. Numerous villages were captured with low Israeli casualties. Arab losses were estimated at 400 dead and 550 taken prisoner. An estimated 50,000 Palestinian refugees fled into Lebanon, some of them fleeing ahead of the advancing forces, and some expelled from villages that had resisted.

In the village of Hula, two Israeli officers killed 58 prisoners in retaliation for the Haifa Oil Refinery massacre (See Part II). Both officers were later put on trial for their actions. One was acquitted and the other received a seven year sentence. Two other villages, Iqrit and Birim, were persuaded to leave their homes by Israeli authorities. They were promised them that they would be allowed to return. Israel eventually decided not to allow them to return, and offered them financial compensation, which they refused to accept. On the other hand any inhabitants of those captured villages that had not resisted Israeli forces were allowed to remain in their villages and became Israeli citizens. By the end of the month, the IDF had captured the whole of Galilee, driven all ALA forces out of Israel, occupied thirteen Lebanese villages and had advanced 5 miles into Lebanon as far as the Litani River.

While there was heavy activity in northern Israel, the IDF and the government were reluctant to invade the West Bank. Ben-Gurion knew that, while Israel was able to absorb Arab villages with small populations, the idea of invading a large area of land with a massive and hostile Arab population was less than appetizing for the IDF. However, just a little further south was the Negev desert, an empty space ripe for expansion, so the main war effort shifted to the Negev. This area was a special concern to Israeli officials because the Bernadotte proposal would have handed the entire Negev over to Egypt and Jordan. This made Ben-Gurion anxious to have Israeli forces in control of the Negev as soon as possible. From early October, Israel also decided to destroy or at least drive out the Egyptian expeditionary force from the Negev. On October 15, the IDF launched Operation Yoav in the northern Negev. The goal of Yoav was to drive a wedge between the Egyptian forces in positions along the coast and the Beersheba-Hebron-Jerusalem road to the east. The operation involved parts of four infantry and one armored brigades (Givati, Negev, Oded, Yiftach and the 8th brigade) and was headed by the Southern Front commander Yigal Allon. They were given the mission to break through the Egyptian lines and to race south driving the Egyptians before them. Because of a lack of depth to the Egyptians defenses the operation did just that, once the IDF broke through, there was little to stop them. Yoav was a huge success, shattering the Egyptian ranks and forcing the Egyptian Army from the northern Negev, capturing 21 villages as well as Beersheba and Ashdod. The only sticking point was the so called Al-Faluja pocket where an encircled Egyptian unit was able to hold out for months. On October 19, In conjunction with Operation Yoav, the IDF initiated Operation El Ha-Har The goals of the operation were to expand the Jerusalem Corridor as far as the western foothills of the Judean Mountains. The operation was carried out by troops from the Harel and Etzioni Brigades. The area was defended by Egyptian units and local militias and by the end of the campaign over a dozen villages had been captured.

The sea was also an area of action during the war. There were clashes between vessels of the Egyptian and Israeli navies in the Mediterranean Sea. In one engagement three Israeli corvettes faced an Egyptian corvette and planes from the Egyptian Air Force. Two of the Israeli ships were damaged, one Egyptian plane was shot down, but the corvette escaped. On October 17, the Israeli navy shelled Majdal and Gaza City. The next day, Israeli naval commandos using explosive-laden boats, sank the flagship of the Egyptian Navy the Emir Farouk and damaged a minesweeper.

On November 9, the IDF launched Operation Shmone to capture the fort in the village of Iraq Suwaydan, 17 miles northeast of Gaza City. The fort's Egyptian defenders had previously repulsed eight attempts to take it, including two during Operation Yoav. Israeli forces opened the attack with strikes from B-17 bombers and an artillery barrage. After breaching the outlying defenses without resistance, the Israelis blew a hole in the fort's outer wall, prompting the 180 Egyptian soldiers inside to surrender without a fight. The defeat prompted the Egyptians to evacuate several nearby positions, including hills the IDF had failed to take by force. Meanwhile, the IDF forces took Iraq Suwaydan itself after a fierce battle.

From December 5 to 7, the IDF launched an operation to seize control of the Western Negev. Called Operation Assaf, the main assaults were spearheaded by the 7th Brigade with the Golani Brigade in support. An Egyptian counterattack was repulsed, and after aerial reconnaissance revealed the preparations for another counterattack, the Israelis launched a preemptive strike, forcing the Egyptians to retreat.

On December 11, 1948, the United Nations adopted UN Resolution 194 which outlined the principles for a final settlement of the war. It was immediately rejected by all of the warring parties.

On December 17, after a period of rest, resupply and maintenance, the IDF launched Operation Horev, the final operation to clear the northern Negev of Egyptian forces, thereby eliminating the threat against Israel’s southern settlements. The first objective of the offensive was the Egyptian army units defending al-Auja on the Palestinian-Egyptian border, then the bases at al-Arish. This would trap the majority of the Egyptian army in the Gaza Strip. On December 27 the 8th Armored Brigade attacked al-Auja from an unexpected direction and after a day of fighting the Egyptians surrendered. The IDF captured Umm Katef and Abu Ageli on the way to Al Arish. Israeli forces subsequently launched raids into the Nitzana area, and entered the Sinai Peninsula on December 28. Yigal Alon, the operational commander, realized that there were no Egyptian defenses left, west of Al-Arish and he prepared to capture the entire Sinai Peninsula. By December 30, Israeli forces were on the outskirts of the Al Arish airfield. At the same time, units from the Harel brigade moved further into Western Sinai. On December 29 the United Nations Security Council ordered a cease-fire and soon after the UN ceasefire, Alon was ordered by David Ben-Gurion to withdraw from Egypt immediately. When Alon questioned the order, Ben-Gurion told him that the British had threatened to invoke the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty of Friendship, and intervene militarily. Meanwhile the Alexandroni Brigade was still fighting to take the Al-Faluja pocket where the encircled Egyptian force, including future Egyptian President, Major Gamal Abdel Nasser, had been able to hold out for four months. When the 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed, the village was peacefully transferred to Israel and the Egyptian troops left.

On January 3, after withdrawing from Sinai, Alon launched an attack against Rafah with the same objective of trapping the Egyptians in Gaza. On January 6, after three days of fighting around Rafah, the Egyptian government announced they were willing to enter armistice negotiations and the IDF subsequently pulled out of Gaza.

On March 5, following a month of reconnaissance, Operation Uvda kicked off, hoping to secure the Southern Negev from Jordan The IDF did not meet significant resistance along the way and on March 10, Israeli forces secured the Southern Negev, reaching Umm Rashrash on the Red Sea at the southern tip of Palestine. Israeli soldiers raised a hand-made Israeli flag ("The Ink Flag") and claimed Umm Rashrash for Israel. The raising of the Ink Flag is considered to be the end of the war.

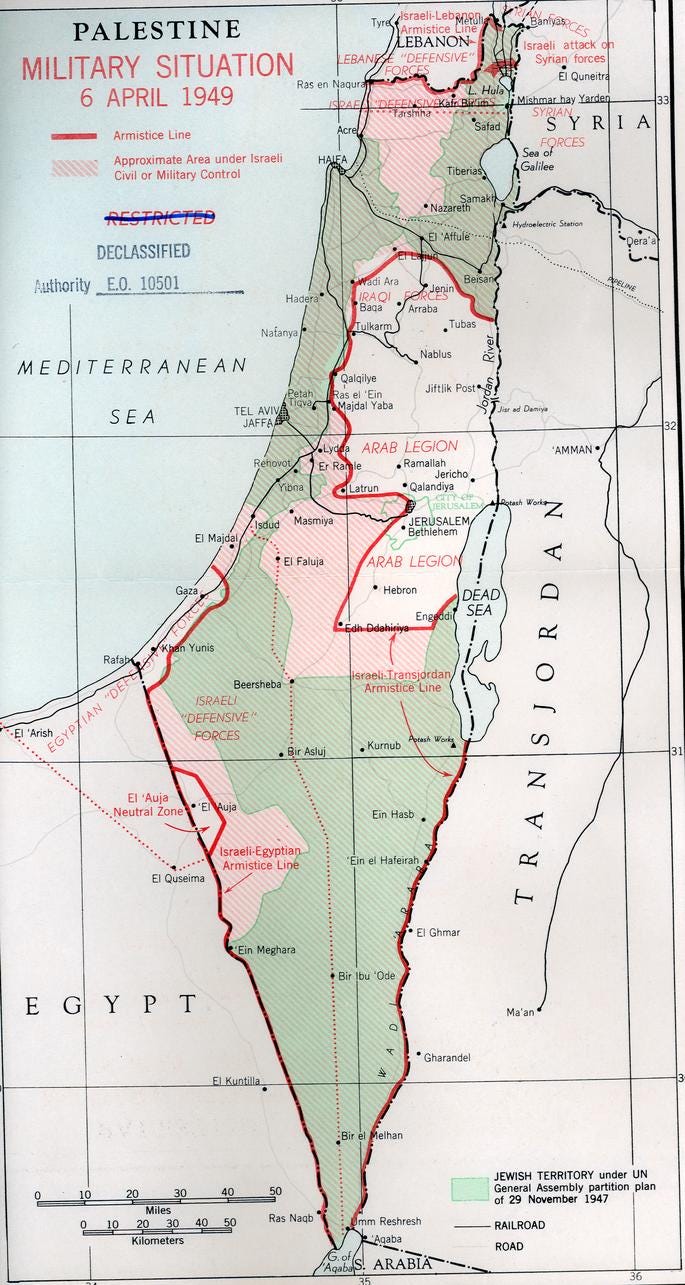

In early 1949, Israel signed separate armistices with Egypt on February 24, Lebanon on March 23, Jordan on April 3, and Syria on July 20. Under the armistice agreements the territory under Israeli control was 78% of the territory comprising the former Mandatory Palestine, or 8,000 square miles, including the entire Galilee and Jezreel Valley in the north, the entire Negev Desert in the south, all of the coastal plain in the center of the country and West Jerusalem. The Gaza Strip was occupied by Egypt and the West Bank and East Jerusalem were occupied by Jordan. The armistice lines between the countries became known as the Green Line. The UN set up two organizations to monitor the ceasefire and prevent isolated incidents from escalating. The United Nations Truce Supervision Organization and the Mixed Armistice Commission.

The war was a costly affair for both sides. Israel lost 6,373 people, about 1% of its population at the time. 4,000 were soldiers and the rest were civilians, with 2,000 being Holocaust survivors. The exact number of Arab casualties is unknown. One estimate places the Arab death toll at 7,000, including 3,000 Palestinians, 2,000 Egyptians, 1,000 Jordanians, and 1,000 Syrians. In 1958, Palestinian historian Aref al Aref calculated that the Arab armies' combined losses amounted to 3,700, with Egypt losing 961 regular and 200 irregular soldiers and Transjordan losing 362 regulars and 200 irregulars. The Palestinians suffered double the Jewish losses, with 13,000 dead, 1,953 of whom are known to have died as a direct result of combat operations.

The Arab defeat also had significant consequences within the Arab world itself. It demonstrated the lack of cooperation and similar goals between the so-called Arab League nations. Every Arab government pursued their own objectives, ranging from King Abdullah’s willingness to accept a Jewish state in return for territorial gains, to Syria and Egypt who wanted to destroy the Jewish state at the moment of it’s birth. The war also de-legitimized the existing leadership in nearly every Arab country involved in the war, leading to instability, revolution and military coups, as we shall see. Of course the biggest problem resulting from the War of Independence (or the 1948 War, if you prefer), was the “Palestinian refugee” problem, a problem that still haunts the region to this day.

That is the last retro post I’ll be doing for now. My next post, which will come out on Tuesday will be about the “Palestinian refugee” issue. I hope you are enjoying getting another look at this important series. With the continuing violence against Israel and the lies that continue to be told about them and the history of this conflict, it is more important than ever for the truth to be brought into the light. As I said at the beginning of this retrospective, I will not fault Israel for anything they do to rid themselves of this evil entity.

Chris